CE453 Surface Water Quality Engineering

Lecture 1. The Regulatory Basis for Water Quality Management

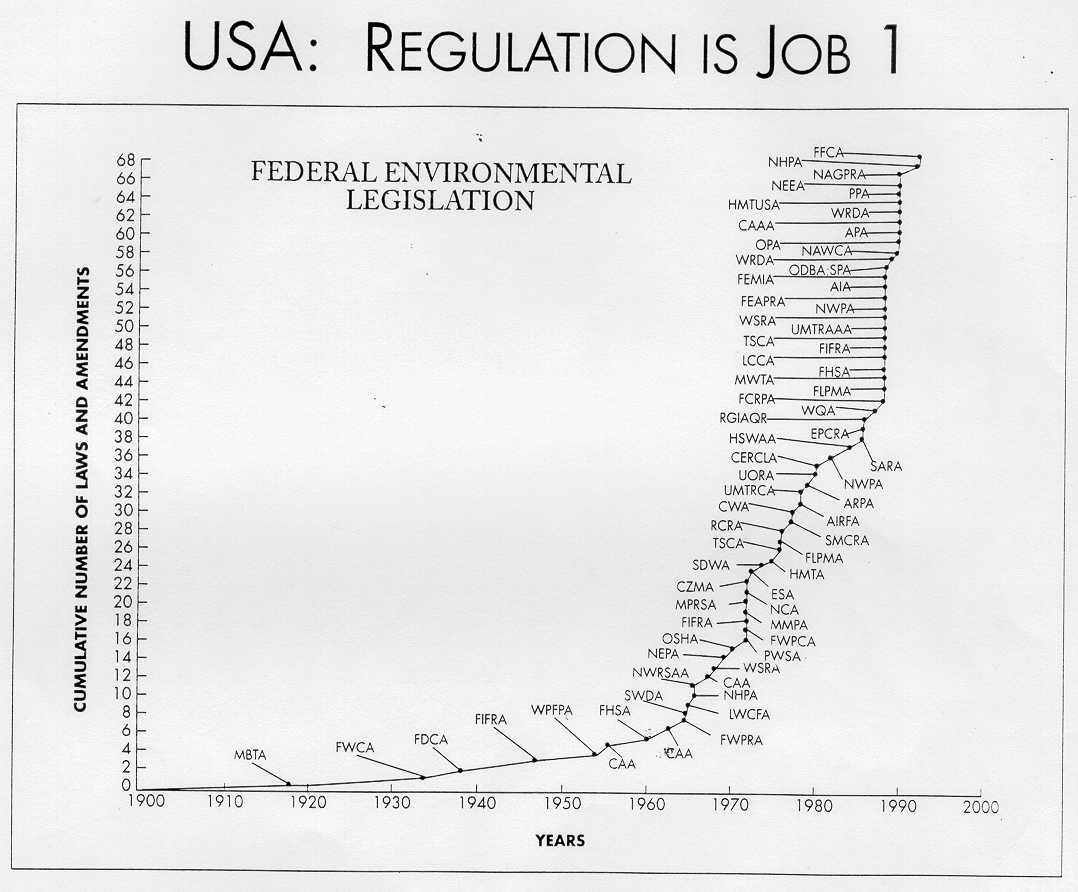

1. Proliferation of Regulations

Environmental legislation and the associated body of regulations are a major part of our lives as environmental engineers and even as private citizens. Although often spoken of in a negative sense, this body of legislation has led to remarkable improvements in the quality of our nation's environment.

Some knowledge and appreciation of the evolution of that legislation is important for engineers who, although driven by those laws on a day-to-day basis, are more often concerned with the end product - the nuts and bolts of an engineered solution. Today I will offer a brief, historical treatment of the evolution of environmental law in the U.S. as it relates to surface water quality engineering.

2. In the Beginning

In the years following the 2nd World War, industrialized countries experienced an economic boom fueled by a burgeoning population, advanced technology, and a rapid rise in energy consumption. During the '50s and '60s this activity significantly increased the quantity of wastes discharged to the environment. Inadequate standards and waste treatment technologies and the increased use of chemicals - fertilizers and new pesticides - caused enormous problems, taxing the capacity of air, water and land systems to assimilate wastes.

In the 1960s a few voices began to speak out on these problems. Stimulated by books such as Rachel Carson's Silent Spring (1962) and events such as the first Earth Day (1968), a groundswell of public environmental activism emerged. Let's look at the regulatory tools which early environmentalists had at their disposal.

3. The Water Pollution Control Act of 1948 (PL 80-845)

This was the first comprehensive statement of Federal interest in clean water programs. From the law, it is "the policy of Congress to recognize, preserve, and protect the primary responsibilities and rights of the States in controlling water pollution." There were no federally required goals, objectives, limits, or guidelines. This led to serious enforcement/compliance problems.

4. The Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899 (Refuse Act)

The weakness of extant water pollution control legislation and the attendant public frustration with the slow pace of cleanup efforts led the Nixon administration in 1970 to resurrect the Rivers and Harbors Act of 1899. This act, originally intended for protection of waterborne transport, prohibited the discharge of solid refuse into the navigable waters of the U.S. This law empowered the Corps of Engineers to issue discharge permits at the national level. This approach failed, however, because there were no criteria or standards upon which to base the issuance of permits.

5. NEPA - the Mother of All Environmental Legislation

The key piece of legislation, laying the groundwork for all the regulation to come, was the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969 (NEPA). This legislation, for the first time, declared a national environmental policy to "insure that presently unqualified environmental amenities and values may be given appropriate consideration in decision-making along with economic and technical considerations. This was a federal commitment to "use all practicable means" to "promote the general welfare" and be "in harmony" with the environment. The policy sought the assurance of "safe, healthful, productive and aesthetically and culturally pleasing surroundings" for all generations of Americans.

One of the most important features of this act was the requirement that "all agencies of the federal government shall include in every recommendation or report on proposals for legislation and other major federal actions significantly affecting the quality of the human environment, a detailed report on the environmental impact of the proposed action" - the Environmental Impact Statement.

Still, environmentalists were dissatisfied. This law had no teeth. It was fine to "cut, burn, and pave" the environment - you simply had to file a report that you were doing it. If the law had teeth it probably wouldn't have passed in the legislative environment of the late 1960s. As it was, the policy statement set the stage for all the legislation which followed.

6. Federal Water Pollution Control Amendments of 1972 (PL 92-500; amended 1977, 1987)

Despite its title (amendments), PL 92-500 did more to set up new laws than to continue existing legislation. Amended as "The Clean Water Act" in 1977, this law was passed over presidential veto and clearly placed ecological concerns over economic considerations - a key house/senate issue in the battle over development of the statute.

Goals and Policy

The objective of the act was to restore and maintain the chemical, physical, and biological integrity of the Nation's waters by:

Specific Requirements and Funding

The act required that municipal dischargers achieve secondary treatment and, to accommodate technological development, apply in the future "best practicable wastewater treatment". Industrial dischargers were required to meet effluent standards applying the "best practicable control technology currently available" (BPT) and in the future install the "best available control technology economically achievable" (BAT). Special effluent standards for selected toxic pollutants were generated. The law authorized $18B in grants to aid in the construction of publicly-owned treatment works (POTWs).

Technology versus Water Quality Based Controls

It is entirely possible, depending on the waterbody and the waste, that technology-based controls (e.g. 2E , BPT, BAT) would not safeguard receiving waters, meeting the "fishable - swimmable" goal of this legislation. In this case, pollution management is driven by water quality based controls. States are required to identify and prioritize all waters within its boundaries where technology-based effluent limitations are insufficient for attainment of the desired water quality. A total maximum daily load (TMDL) is then established for pollutants limiting attainment of the desired water quality. This practice ultimately leads to additional controls enforced by a permit, monitoring, and compliance program. In some watersheds, effluent trading is being examined as a means of meeting TMDLs.

National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES)

Effluent limitations were now backed by water quality standards in addition to the technology-based limits. All point source dischargers were required to obtain a permit from federal or designated state authorities. Permits were accompanied by monitoring and reporting requirements and compliance assured by a system of fines: willful violator ($25,000/day/violation and 1-year in jail), repeat willful violator ($50,000 and 2 years), non-willful and filing of false statements ($10,000).

7. Safe Drinking Water Act of 1974 (amended in 1986 and 1996)

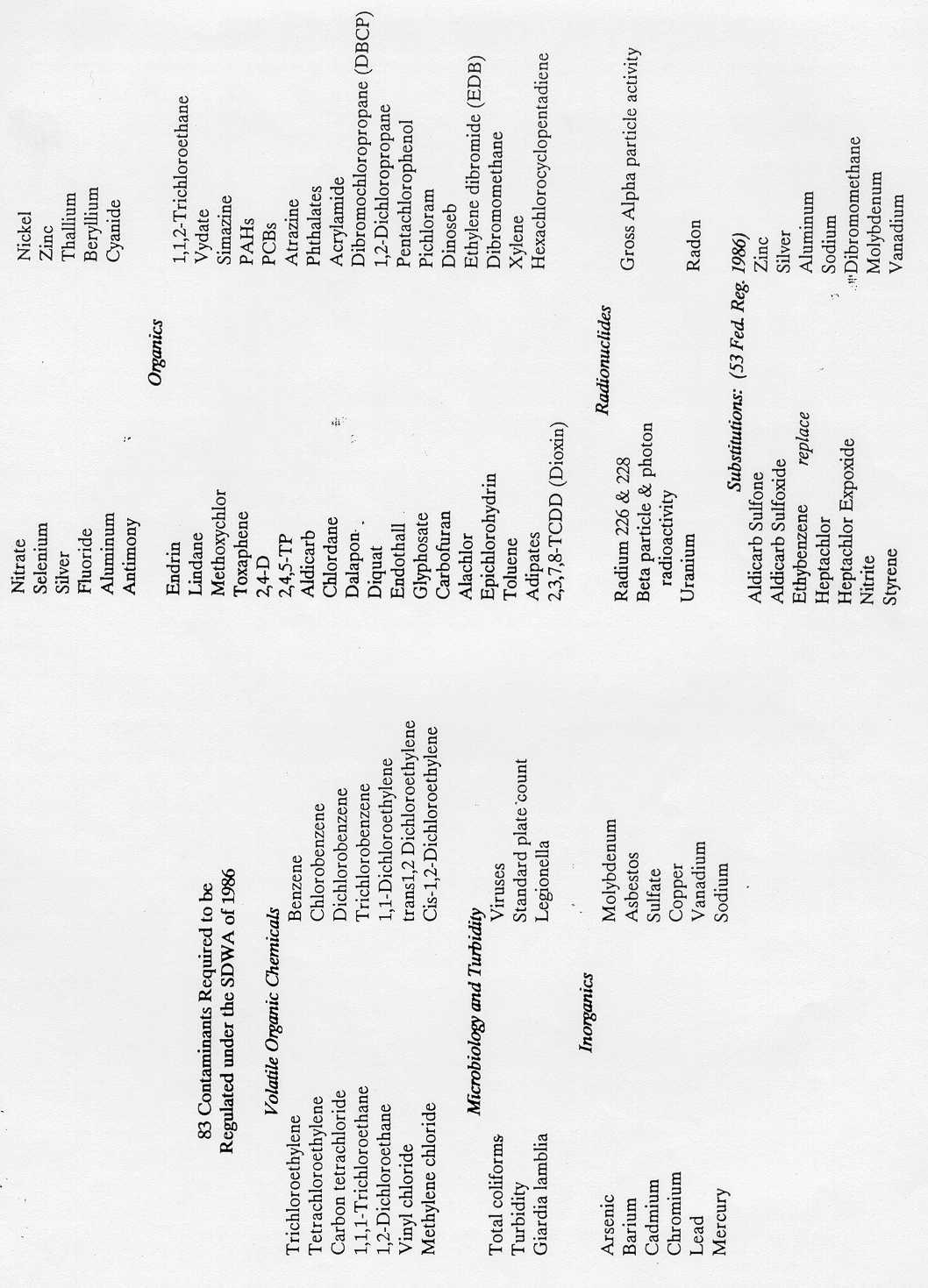

The Safe Drinking Water Act federalized regulation of drinking water systems and required EPA to set national standards for levels of contaminants in drinking water. Under the SDWA, EPA has set primary standards (maximum contaminant levels, MCLs) for 27 pollutants with the potential to endanger the public health. Primary MCLs have been developed for 10 organic chemicals, 11 inorganic chemicals, 4 radionuclides and 2 microbiological contaminants and are federally enforceable. Secondary standards (maximum contaminant levels, MCLs) have been developed for an additional 82 parameters of primarily aesthetic significance, including chloride, iron, and color. Secondary standards are not federally enforceable, but are intended as guidelines for state regulatory agencies. Primary and secondary standards apply to finished water. The Surface Water Treatment Rule (SWTR) establishes source water standards for the rivers, lakes, and reservoirs which provide drinking water. The SWTR establishes additional standards for turbidity, coliform bacteria, protozoan pathogens, and disinfection byproducts. The proposed Enhanced Surface Water Treatment (ESWTR) and Disinfectant/Disinfection Byproducts (D/DBP) rules will further strengthen these regulations. These features of the SDWA are having tremendous impacts on the water supply industry, drawing the attention of surface water quality engineers.

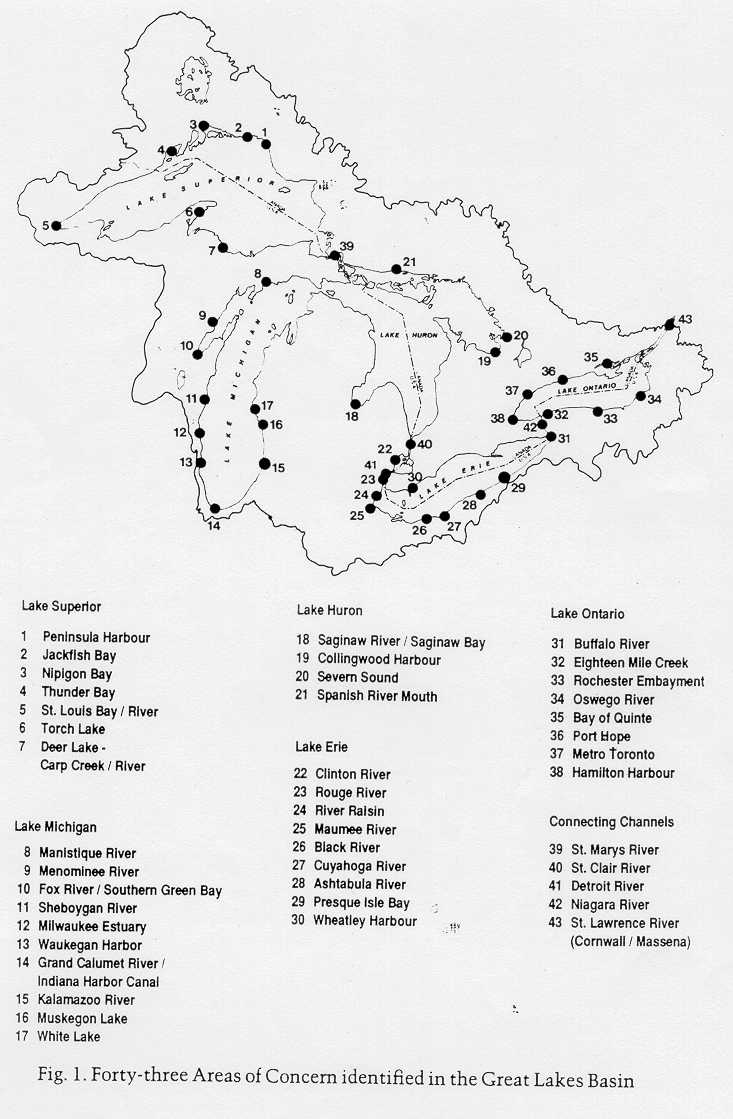

8. Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement

Of particular interest to us are provisions developed under the 1972 Great Lakes Water Quality Agreement between the U.S. and Canada. In an effort to control eutrophication, POTWs discharging to the Great Lakes or tributary waters must limit their effluent phosphorus to 1 mg/L. Specific sites on the lakes not meeting the desired water quality, termed areas of concern (AOCs) were targeted and remedial action plans (RAPs) are being developed. Toxic substances have been of great interest - with an effort made to seek zero discharge and encourage pollution prevention. Most recently, officials have been discussing the issue of water export from the Great Lakes.

9. State and Local Standards

It remains the responsibility of the state and local governments to adopt and enforce water quality standards. While the framework for this activity emerges from the federal level, it is most common for engineers to interact with the state (e.g. Michigan Department of Environmental Quality) and local (Western UP District Health Department) regulators in their daily work.

10. Summary

The body of environmental legislation offers us a mandate for action through its definition of "water use" and designation of related criteria and standards. The role of the environmental engineer is to design, test, and implement public works which will permit the growth of society, while protecting the quality of the environment. Surface water quality engineering bridges the regulatory and implementation phases of the process, offering design analysis to specify required levels of treatment and testing proposed management options.

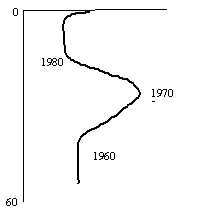

Phosphorus content (x-axis, mgP/kgDW) of sediments from Onondaga Lake in Syracuse, NY as a function of sediment depth (y-axis, cm). Because sediment deposition rates are relatively constant, the y-axis can be viewed as a time scale.

D.V. Ager (1981) suggested that, "The history of any one part of the earth, like the life of a soldier, consists of long periods of boredom and short periods of terror." Onondaga Lake's short period of terror began in the post-war period of the 1950s when population growth and the increased use of phosphate detergents led to increased inputs of phosphorus. Later, in the 1970s, environmental legislation was passed to ameliorate some environmental problems. One piece of legislation banned the use of detergents containing phosphorus. The impact of this legislation is mirrored in the sediment phosphorus profile of the lake.