|

Reserve Text: from Anthony Easthome, Poetry as Discourse, London: Methuen, 1983. Chapter 4: Iambic pentameter

The Russian Formalists

and the Prague School of linguists considered the one universal condition

of poetry, its constitutive principle or dominanta, to be its organization

into lines. Tomashevsky writes:

In poetry the line boundary is not arbitrary but is determined by a system of equivalences operating from line to line. In different languages and cultures line equivalence or metre is established on different bases. Four main systems can be distinguished: the number of syllables in a line, syllable duration, tone, stress. So in Hungarian folk poetry the only requirement for an utterance to constitute a line is that it should have six syllables. Classical Greek and Latin poetry is organized with recurring patterns of long and short syllables. Chinese is a predominantly monosyllabic language with a very limited number of syllables but it |

|

[52] quadruples its

syllabic resources because each may occur in four different tones (level,

rising, rising and falling, level and falling). Classical Chinese poetry

is organized mainly with four-, five- and seven-syllable lines patterned

through an opposition between the level tone and the other three 'deflected'

tones in a Systems rarely

operate through only one principle of organization. One may be dommant,

but is often mIxed wIth others. In Modern English, iambic pentameter

requires both a patterning of stressed and unstressed syllables and

a set number of syllables per line, and while the classical metres of

Greek and Besides these four

main principles others are possible. Classical Hebrew poetry, for example,

is made up with end-stopped lines divided by a caesura into two parts

or cola. These are related in a complex system of synonymous

and antithetic parallelism which is semantic and syntactic. In this

it remains an exception to the general rule by which in different languages

the poetic line is organized phonetically, that is, in terms

of the physical properties of language. Thus metre generally inscribes

precedence of the signifier into the very basis of poetry. As Lacan

comments in referring to a stanza by Valery:

If the material

basis of poetry is recognized in metre, in the 'parallelism of the signifier',

the ensuing question must be how different metres are historically specific. In 1912 Ezra Pound set himself the principle of composing 'in |

|

[53] the sequence of

the musical phrase, not in sequence of a metronome' (1963, p. 3). A

generation later Brecht, in an essay of 1939, rejected 'the oily smoothness

of the usual five-foot iambic metre' (iambic pentameter in German and

English are closely comparable) and describes how he 'gave up iambics

entirely and applied firm but irregular rhythms' (1964, p. 116). The

political contrast of fascist and communist, Pound and Brecht, is so

striking it obscures the grounds they share. Both reject liberalism

and the notion of the transcendental ego. For Brecht 'the continuity

of the ego is a myth' (ibid., p. 15), while according to Pound, 'One

says "I am" this, that, or the other, and with the words scarcely

uttered one ceases to be that thing' (1960, p. 85). Both champion oriental

art forms as a means to criticize and oppose the Western Renaissance

tradition, the bourgeois tradition. Both advocate free verse. Their work provides

a point from which to interrogate the traditional prosody of English

poetry, accentual-syllabic metre; most typically represented by iambic

pentameter. Despite significant historical developments in practice--notably

Augustan correctness in the couplet followed by Romantic relaxation

there is a solid institutional continuity of the pentameter in England

from the Renaissance to at least 1900. Like linear perspective in graphic

art and Western harmony in music, the pentameter may be an epochal form,

one co-terminous with bourgeois culture from the Renaissance till now. Yet the free verse practice of Pound and Eliot opens a gap at the margin of the traditional prosody which is usually closed as follows: pentameter is normal in Modern English because it arises naturally from the English language itself. Prised away from its home in poetry, pentameter becomes immediately re-naturalized in language. This view, widely diffused and casually repeated, mainly derives from what even now remains the standard work, Saintsbury's History of English Prosody in three volumes, 1906-1910. Saintsbury's premise is that 'every language has the prosody which it deserves' (vol I, p. 371) and so iambic metre corresponds to the inherent rhythms of the English language. Established first by Chaucer, it was obscured during the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries due to linguistic change, particularly the 'lopping off of the final syllable' (ibid., p. 292); but with this uncertainty resolved, iambic metre (like [54] the British Constitution

in the Whig theory of history) emerged naturally in what Saintsbury

calls 'an unbroken process of development' (ibid., p. 372). One may argue against

this linguistic determinism in two ways. First, even if it is true that

a language gets the prosody it deserves, another metre may claim to

be more natural to English. Besides iambic

pentameter there is the older accentual four stress metre inherited

from Old English poetry. While the pentameter,

conventionally defined as a line of ten syllables alternately unstressed

and stressed, legislates for both stress and syllable, accentual metre

requires only that the line should contain four stressed syllables and

says nothing about the unstressed syllables. Since stress or syllable

prominence is phonetically much more significant in English than syllable

duration, accentual metre has a strong claim to be more natural in Old,

Middle and Modern English. Its case is vigorously put

Second, iambic

pentameter did not simply emerge from the language: it was an historical

invention. In fact it was invented twice. The first time was in the

fourteenth century when it took the form of Chaucer's Middle English

pentameter. Between then and the early sixteenth century massive phonological |

|

[55] metres at the Renaissance,

as Saintsbury well knew, since he says that its establishment the second

time was due to 'Italian influence, classical influence, and the two

as combined and reflected by Spenser' (1910,1, p. 303). Promoted into

dominance by the new courtly culture, pentameter is an historically

constituted institution. It is not natural to English poetry but is

a specific cultural phenomenon, a discursive form. In rejecting Saintsbury's

assumption that language determines metre there is no need to deny all

determining force exercised by language on metre. Modern English clearly

constitutes a precondition for pentameter, as can be seen in several

ways. Stress is an important linguistic feature in Modern English and

pentameter exploits it. Stress is inherent in the isolated word when

it is of more than one syllable, and a full account of this is offered

by Halle and Keyser (1971). They give the rules we operate in knowing

how to place primary stress by saying 'America' instead of ,

America', 'arthritis' not 'arthritis', and so on.

As soon as isolated words are combined into phrases , the stress they

hold in isolation is modified by context. A form of this is isochrony:

the tendency to keep roughly the same time interval between stresses

so that (in Attridge's excellent illustration 1982) the two syllables

of 'John stands' is timed roughly the same as the six of "jonathan

understands," both having two strong stresses, in contrast to 'Johnny

Black withstands', which has three. There is also a

preference for alternating strong and weak stresses to give 'bright

and shining eyes' rather than 'shining and bright eyes' with two strong

stresses adjacent (see Bolinger 1965). In prescribing a regular spacing-out

of stress along the line pentameter makes use of the tendency to isochrony

and Not concerned with unstressed syllables, it accommodates itself easily to the wayisochrony demotes syllables between stresses, while pentameter insists on them, being concerned with the number of syllables in a line. Modern English, then, is a determinant for iambic pentameter but not the only determinant.

Pentameter and

Language

[57]

and a recommendation of cannibalism

A syllable can be emphasized by means of stress but also by accent, that is, through its place in one of the many strongly varied intonation contours of English. The relation of stress and accent remains controversial in linguistics. David Crystal argues that both stress and accent are produced by a 'bundle' of phonetic features, not just one, and that in 'stress, the dominant perceptual component is loudness' while in accent it is pitch (1969, p. 120). Both stress and accent have to be considered together in defining what makes a syllable more or less prominent in an utterance. Roger Fowler (1971, p. 175) summarizes four factors contributing to syllable prominence: that inherent in the isolated word when it is of more than one syllable (cf. Halle and Keyser 1971); that due to a sub-sentence stereotyping, for instance of the kind which prefers 'bright and shining eyes' to 'shining and bright eyes'; that ensuing when a word is picked out for emphasis for semantic reasons (as intonation signals difference of meaning in Delattre'sexample); that which occurs through the normal functioning of intonation contour.

draw two conclusions.

First, the concept of stress alone is entirely insufficient to explain

syllable prominence, and accent as effected holistically by the intonation

contour must be considered as well. Second, if only because of the role

of intonation, syllables do not occur in a simple contrast between prominent

and unprominent but have degrees of prominence relativized by the context.

Prominence and unprominence donot function like bricks added together

to make a wall but like the relative values 2 Another doubtful development in linguistic work on metre also follows from giving theoretical priority to syllable and stress, to units within the line rather than the line itself. One area of the discussion has come to operate on the basis of an epistemological error. This is the 'generative metrics' of Halle and Keyser (1966 and 1971), Magnuson and Ryder (1970 and 1971), Kiparsky and--ironically --Attridge (1982) (ironically because in his second chapter on 'Linguistic Approaches' Attridge provides one of the best critiques of the procedure). The theoretical

principle of this tendency is explicit when Halle and Keyser announce:

The assumption is that each line of pentameter actualizes the rules of metre in the same way that rules in transformational grammar can show how sentences are generated through transformations in the relations between surface and deep structures. The hoped for result is 'acceptable' and 'unacceptable' lines of pentameter on the model of grammatical and ungrammatical sentences. But pentameter is not a structure elaborated by rules [59]

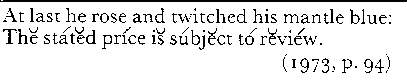

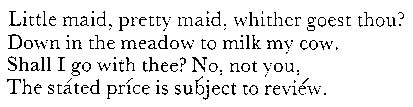

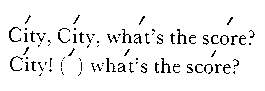

On this principle, that of the perception of a gestalt, any line in a passage of iambic pentameter tends to become iambic pentameter. Raymond Chapman points out the way a sentence from daily speech ('the stated price is subject to review') can turn into pentameter when inserted into that metrical context: But the same utterance--the

same intonation--will also function perfectly as a four-stress line

in accentual metre: In both cases the

set of metric expectations imposes itself on the same utterance to make

an acceptable line in two different metres. The metre makes the line

while the line supports the metre. That definitions of pentameter should begin with the culturally established pattern is shown by the fact that the pentameter norm can be perceived entirely apart from lines--that is, in prose. Commenting in detail on a passage fromVirginia Woolf's novel Mrs Dalloway Traugott and Pratt note that

An

even more impressive instance occurs in a speech by Vladimir in Waiting

for Godot beginning 'Let us not waste our time in idle discourse'.

This establishes the 'idea' of the pentameter in association with a

certain humanist rhetoric only in order to mock both. A number of regular

'lines' ('. ..tho'se cries fo'r help This happens less

often than people think, as would have been apparent if the linguistic

discussion of metre had paid more attention to free verse. As Graham

Hough has shown (1960) much of what passes for free verse, including

Eliot's 'Prufrock' and one of Lawrence's more polemically free verse

poems, turns These two general criticisms of work on metre concern intonation and the pattern of pentameter. The implications lead back to a definition of pentameter as counterpoint. As applied to pentameter the term metre has meant ambiguously the 'official' metrical pattern itself (ten syllables alternately unstressed and stressed) and the pattern as practised in relation to syllables made prominent in the intonation of a line. Both in fact are needed to specify the pentamet.er, which is defined by the relation of two systems, the abstract metrIcal pattern and the mtonatlon of non-metrical language. On this there is a definite consensus [61] |

|

among linguists

and literary critics. In 1949 Wellek and Warren wrote that:

More recently,

introducing a selection of articles on metre,' Chatman and Levin summarize

a now general agreement:

The term counterpoint is preferred here because of the currency given it first by Hopkins and later by Yvor Winters. It designates the metre as function of two forces, the vector between two axes. One is the abstract pattern ti-tum ti-tum ti-tum ti:'tum ti-tum, a grid of expectations explicitly formulated within British culture and sufficiently confirmed within a poem to fix the pattern as totalized gestalt. The grid enables both

and

to constitute pentameter, even though, as E. M. W. Tillyard says in citing them, the lines are 'as different as they can be except in that

the pattern behind them is the same' (1929, p. 18). On the other side

there are' the prominences and unprominences of the syllables produced

in the non-metric usage. It is not the case that the official pattern

is a metrical 'abstraction' and its practice in counterpoint an 'actualization'

of this abstraction; rather the counterpoint is the metre. This can be substantiated

through two comparisons. 2 English pentameter can be compared with the model of classical hexameteh The abstract pattern of Latin hexameter is defined by the Oxford Classical Dictionary as follows:

refuse to put a

dactyl at the fifth foot ('an Alexandrian mannerism', as the Oxford

Classical Dictionary notes). The term metre accurately includes

both the abstraction and its actualization, and the composition of Latin

verse becomes a mechanical operation which slots in the abstract pattern

are filled using a Latm dIctIonary, which defines the correct length

of each syllable, and Gradus Ad Parnassum, a special dictionary

for verse composition, which gives metrical synonyms. Contrast with

this model shows how the English pentameter works. ' In English, the abstract pattern is ten syllables, alternately unstressed and stressed. In the Latin model, length of syllable is absolute and durational contrast is binary (not least because [63] But as the earlier

discussion of accent and intonation sought to show, syllables in English

do not occur in a simple binary contrast between prominence and unprominence,

and degrees of prominence in an utterance are always contextually relative.

Since syllable prominence is relative, it follows that the abstract

pattern of pentameter is never actualized (except of course by the line

boundary) but that syllable prominences and unprominences in the non-metric

intonation approximate it. This approximation is the metre. 2 Pentameter can

be compared with the older, accentual metre, a comparison which confirms

that pentameter is to be defined by approximation rather than coincidence

between abstract pattern and non-metrical intonation. The abstract pattern

of four-stress accentual metre anticipates four equally prominent syllables

in each line. Since numbers of unstressed syllables are not regarded

as significant for metrical purposes, syllable prominence provided already

by the non-metric intonation of an utterance will readily and necessarily

coincide with some of these four metric positions. Where they do not,

or do not do so sufficiently strongly, the expectations set up by the

abstract pattern will intensify what stress there is, as it did to the

sentence, 'The stated price is subject to review' when this was inserted

into the context of accentual metre. As a result, prominences anticipated

by the abstract pattern and those preexisting from non-metric intonation

will coincide and reinforce each other. Hence the high prominence of

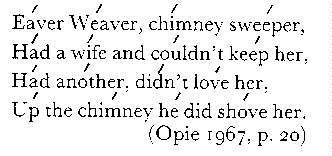

syllable, the heavily stressed rhythms, of accentual verse:

Here a line of

six syllables and one of eleven constitute two metrically regular lines

in a metre specified by reinforcement, not counterpoint. Pentameter can

be performed as though it were accentual metre; that is, thumped out

as doggerel so that abstract pattern and intonation coincide. This is

how children and the inexperienced, used mainly to accentual metre (for

example, nursery

Spoken performance

of pentameter is accordingly open to variation in a way accentual verse

is not. Since pentameter consists neither of the abstract pattern itself

nor the intonation of non-metric language but is a function of the two

in which both are active, actual performance will vary widely according

to whether the voice tends towards the abstract pattern (though never

losing hold on the intonation) or towards the intonation (though it

could only become non-metric speech by defying entirely the abstract

pattern). The metre can be

seen not as a neutral form of poetic necessity but a specific historical

form producing certain meanings and acting to exclude others. [65] These meanings

are ideological. Though they persist in and with the metre, they surface

most manifestly during its founding moment, at the Renaissance. Pentameter

comes to power as a neo-classical form and this is inscribed into its

defining feature of counterpoint. On the one side, as the name proclaims,

iambic pentameter reaches back to the quantitative metre of Greek and

Latin and the model ofbinarily contrasted syllables arranged in 'feet';

on the other, the non-metric intonation approximates to the abstract

pattern and thus the native language is brought into relation with the

classical model. So a particular practice of the national tongue can

dress itself in the clothes of antiquity and a bourgeois national aspiration

may represent itself in the form of universal civilization (see Kristeva

1974, p. 210). The pentameter is favoured by the English court at the

Renaissance --in 1589 Puttenham praises Wyatt and Surrey on the grounds

Once established

as national poetic institution pentameter becomes a hegemonic form.

It becomes a sign which includes and excludes, sanctions and denigrates,

for it discriminates"the 'properly' poetic from the 'improperly'

poetic, Poetry from verse. In an unbroken continuity from the Renaissance

to 1900 The hegemony of

pentameter continues to promote certain meanings rather than others: 1 Abstraction

Relative to accentual metre whose requirement off our stresses admits

a wide variety of line lengths, the abstract pattern of pentameter is

abstract in a specific and restricted fashion. It represents a systemic

totality, an explicit preconception legislating for every unit of stress

and syllable, and this 'continueth throughout the verse' (Gascoigne),

'in sequence of a metronome' (Pound). The only relief from this uniformity

is the intonation, which even so always implies the comprehensive grid

to which it approximates. Pentameter accordingly shares the prestige

attaching to abstract and uniform modes. Marshall McLuhan has suggested

an historical significance for such modes; the heterogeneity and simultaneity

of feudal culture, its 'easy habit of configuration',

2 Concealed

production Yet the abstraction of pentameter is never openly announced

as such. According to the contradictory nature of the metre, counterpoint

being its specific effect, the abstraction of the pattern is always

produced in relation to the apparent spontaneity of the intonation contours

in ordinary speech. To this extent the severity of the abstract pattern

is always mitigated. The 'smoothness' Brecht notes, the tendency of

verse in iambic metre to 'glide past the ear' because its (regular)

rhythms 'fail. ..to cut deep enough' (1964, p. 120), has been welcomed

as desirable for the English poetic tradition.

Robert Graves and

Laura Riding have made an explicit claim for the political significance

of counterpoint: In pentameter intonation

approximates to the abstract pattern but can never coincide with it.

Because of this feature, as the previous quotations show, counterpoint

has yet another ideological connotation. For it corresponds to the ideological

opposition between the 'social' and the 'individual', an opposition

which envisages society as a 'necessity' against and within which the

individual finds his or her 'freedom'. Normally (that

is, in casual discourse), there would be no problem; the first of the

similar sounds would be omitted by a variety of elision . . . It might

sound somethIng like, 'When I Ajak' strive' some Rock's vast Weigh'

to throw'. (1978, P.44) : However, the 'formal

style of poetry reading, even in silent reading' means that this elision

does not operate and so to say 'Ajax-strives' without elision 'requires

a pause, an actual "cessation of phonation'" (ibid., p. 44).

This is an extreme example of a feature typical of English poetic discourse.

Elision of some degree is invited whenever the sound at the end of one

word and that at the beginning of the next is close in point of [69]

Pentameter aims to preclude shouting and 'improper' excitement; it enhances the poise of a moderate yet uplifted tone of voice, an individual voice self-possessed, self-controlled, impersonally self-expressive. The topic of pronunciation

takes analysis of ideological meanings right up to the question of subjec Pentameter and

subjectivity Meaning 'insists'

along the syntagmatic axis, and so the attempt to close meaning along

this axis offers a coherent position to the subject as 'a single voice'

sustaining meaning and itself sustained in 'this linearity' (Lacan 1977a,

pp. 153-4). The fixity of this position for the ego appears transcendental

simply there rather than constructed -when the process of discourse

which in fact produces the position is generally backgrounded and denied. Relative to other

metres, English iambic pentameter is a syntagmatic form and works to

promote a position for the reader as transcendental ego. It does so

while operating in the the line.. In expanding

these assertions it will be useful to bear in mind a contrast between

pentameter and the older four-stress metre, as well as the model of

classical metre. The way pentameter

enforces coherence and unity in meaning has been convincingly evidenced

by Donald Davie. Taking Pound's free verse exploration of a landscape,

'Provincia Deserta', Davie re-writes it in iambic pentameter (1965,

pp. 60-3). The whole exercise needs to be read but some salient points can be picked out: 'the pentameter makes the creeping and peering happen together, whereas in Pound's poem the man is seen first to creep, and then to peer. ...In the blank verse weare told that the Dronne has lilies in it; we do not discover it for ourselves as the speaker did. InPound's poem the speaker sees the road wind eastwards, and then reflects that Aubeterre is where it leads to. ...In the blank verse Aubeterre and the road are parts of a single act. ..'. Davie's conclusion is that:

The effect of pentameter

is to run together and unify (Davie's word is 'interweave') subject

matter and meaning.. The reason for

this is that while all metre is precisely linear, an organization along

the line closing at the line boundary,pentameter is linear ~o a s~ecial

~e~ree. It points horizontally along the syntagmatIc cham. ThIs IS the

case both within the line and across lines. Within the line Paul Kiparsky

has pointed to the relative nature of stress in pentameter, the fact

that the degree of stress is not absolute but exists by virtue of the

greater or lesser stresses next to it--'syntagmatically' --(rather than

by virtue of the greater or lesser stresses that might have occured

instead of it -'paradigmatically'). ...(1977, p. 194) In the Latin verse

model preformed units of long and short syllables can be substituted

in the line without otherwise affecting the metre. This cannot happen

with pentameter(as anyone knows who's tried it) because pentameter depends

upon syllable prominence and this is relative to context- the preformed [71]

This means that

when we reach the ehd of the line there is no compelling pressure from

the larger structure to register the completion of a rhythmic unit and

to move on to the next one. Instead, the syntax

has a more powerful voice. ..and will determine whether we pause or

read straight on to the following line. (1982, p. 133) The predominantly

syntagmatic structuring of pentameter determines subject position in

two ways simultaneously. These can be distinguished according to whether

counterpoint is thought 'up' from the intonation towards the abstract

pattern or 'down' from the pattern onto the intonation. On one side

that

The single voice that 'comes most naturally when we soliloquize' tends to be over-personal; through 'a powerful and passionate syntax' enforced by traditional metres the voice can be raised towards 'impersonal meditation'. That is: syntagmatic closure promoted by the pentameter can approximate to a poise and self-consistency that seems absolute (Yeats identifies it with art, the ideal, impersonality and indeed eternity). But on the other side this autonomy is effected by the pentameter only at the cost of increased repression: the abstract pattern contains and overrides process as enacted in the intonation. In fact Wordsworth and Coleridge, whose programmatic commitments might have been expected to lead them to free verse, both make finely conservative spokesmen for the repressive effectivity of what their practice reveals to be essentially traditional pentameter. Coleridge traces the origin of metre to that 'spontaneous effort' of the mind 'which strives to hold in check the workings of passion' (1949, II, p. 49); Wordsworth takes the view that excitement may get out of control (be carried beyond its proper bounds') and that metre has 'great efficacy in tempering and restraining the passion' (1965, p. 264).

If the speed is

slowed down, however, intermediate stresses make themselves felt. ..,

causing the listener to reinterpret the passage in two-syllable measures.

This should cause no wonder, since it is a well-known fact of English

rhythm that the slower the speed at which an utterance is spoken, the

greater the proportion of stressed to unstressed syllables. (1969, p.

I 17) But pentameter

requires this slower pace since its abstract pattern looks for a binary

uniformity of stressed and unstressed [73] syllables. It acts to restrain, to withold and release stress in an even distribution through the line. The intonation of an extra-metric utterance (Tye up the knocker, say I'm sick, I'm dead') rising to two equal peaks ('I'm sick, I'm dead') is ironed out by the abstract pattern of the metre. Accordingly, pentameter provides space for certain polysyllabic words and so encourages a certain vocabulary and register in poetry. (A full account of this would be the subject of another study along lines laid down by Mukarovsky, 1964, pp. 113-32). To sum up: accentual metre preceded pentameter in English and became subordniated to it at the Renaissance though continuing in popular forms such as children's rhymes:

In accentual metre

the stress of the intonation and the abstract pattern coincide and reinforce

each other; in pentameter they are counterpointed. The coincidence in

accentual metre calls for an emphatic, heavily stressed performance,

one typically recited or chanted, often in association with rhythmic

gestures, [74] Poetry as Discourse |

|

and so to a single

voice in the closure of its own coherence. Try speaking 'Humpty-Dumpty'

and then Milton on his blindness ('When I consider how my light is spent',

etc.). F. R. Leavis was

right to assert that English poetry in the dominant discourse 'depends

upon the play of the natural sense movement and intonation against the

verse structure' (1967, p. 50); by accommodating 'i<!!.?matic speech'

(ibid.) poetry becomes as though transparent to the presence ora represented

speaker, an effect 'as if words as words withdrew themselves from the

focus of our attention and we were directly aware of a tissue of feelings

and perceptions' (p. 47). Four-stress metreand for that matter free

verse -forces attention to the words as words and so shatters any effect

of transparency. Relative to other

forms of discourse all poetry can be seen to foreground the signifier.

In four-stress accentual metre (to persist with the example) the coinciding

reinforcement of abstract pattern and intonation puts the sound of the

words before their meaning -it exhibits metricality and openly celebrates

rhythmic pleasure in the work/play of the signifier. In contrast, pentameter

would disavow its own metricality and restrain the activity of the signifier.

ln this lies the central effect of pentameter, an effect which can be

made visible by reference to the distinction between enunciation and

enounced as developed in Chapter 3. There is always necessarily a disjunction

for the subject between its position as subject of and for the enounced

and its position as subject of and for the enunciation (on which the

former position depends). When I speak a line of poetry (such as that

of the Milton sonnet just now) I am placed as subject of the process

of enunciation and only thus may come to occupy a place as subject of

the enounced, 'Milton' considering his blindness. Iambic pentameter

works to deny the position of subject of enunciation in favour of that

of the subject of the enounced; it would disclaim the voice speaking

the poem infavour of the voice represented in the poem, speaking what

it says. Accordingly

By eliding metricality

in favour of '.the prosody of natural speech' the pentameter would render

poetic discourse transparent, aiming to identify the speaking of a poem

with the speaking of a represented speaker or a narrator; it invites

the reader into a position of imaginary identification with this single

voice, this represented presence. The discussion

of pentameter has meant to show the cohesion of English bourgeois poetic

discourse by analysing iambic pentameter as a necessary condition of

its possibility. The dominance of the metre since the Renaissance gives

it a claim to be an epochal form, and ,a similar analysis might be made

of In leaving the question of metre two points of qualification need to be made. First, iambic pentameter, by far the most widely used form, has been taken to typify accentual-syllabic metre in English. There has been no account of other iambic forms or of the other metres, trochaic, anapaestic and dactylic. I see no reason to doubt Martin Halpern's conclusion that these all resolve themselves into two types: of the four so-called 'syllable-stress' metres in English iambic, trochaic, anapaestic and dactylic--only the iambic has developed in a direction radically different from the native accentual tradition. ..the other three, as characteristically used in English poetry, are simply variants of the strong-stress mode. (1962, p. 177) Second, there has

been a degree of abstraction at work in analysing iambic pentameter

apart from its use in a particular moment of the historical

process. The abstraction has been necessary. It is a temporary and provisional

'freezing' of other factors in order to isolate and understand the material

effect of the metrical form. Of course in practice the metre is always

active in conjunction with many other features. Clearly, in the aggressive

early days of the struggle for bourgeois hegemony, especially around

1600, the pentameter had a novelty and glamour that was long gone in

1900. Now the pentameter is a dead form and its continued use (e.g.

by Philip Larkin) is in the strict sense reactionary. Eliot wrote in

1942: 'only a bad poet would welcome free verse as a liberation from

form. It was a revolt against dead form, and a preparation for new form'

(1957, p. 37). The cohesive identity

of English poetic discourse continues through historical change. To

deal with this I shall look at four sample texts from four crucial conjunctures

in the history of the discourse: the Renaissance, obviously enough the

founding moment of the discourse and so particularly likely to show

how it works; the 'high plateau' of the discourse when it was consolidated

during the Augustan period; its renovation by Romanticism, when changes

are introduced whose effect is to keep it the same; and finally the

crisis of the discourse when the Modernist revolution challenges it

at every level. English poetic

discourse is rooted in the pentameter. Through it certain ideological

meanings and a subject position are 'written into' the discourse. Pentameter

defends the canon against the four-stress popular metre, which foregrounds

the po~m as a poem; it promotes the 'realist' effect of an individual

voice 'actually' speaking. To provide this, a position for the reader

as subject of the enounced must be fixed in a coherence, a stability

'of its own'. Fixity is achieved mainly in two ways: as signifier is

held firmly onto signified in the syntagmatic chain, as ' the work/play

of the signifier is denied. Here are to be found the relevant terms

for analysing historical variation with reference to the four examples.

Each chapter will begin with a discussion of attitudes towards language

in each period. Other related topics and terms for their analysis -the

referential effect and iconicity, for example -will be introduced and

explained as they come up. It is not easy to shake off the familiar assumptions brought [77] |

|

Works Cited: Althusser, Louis,

1977, Lenin and Philosophy and Other Essays, tr. Ben Brewster

(London: New Left Books). Bolinger, Dwight

L., 1965, 'Pitch accent and sentence rhythm', in l -1977b, The

Four Fundamental Concepts of Psychoanalysis, tr. Alan Sheridan (London:

Hogarth Press). -I971, 'Second

thoughts on English prosody', College English, 33, 198-2I6. Ong, Walter J.,

1982, Orality and Literacy (London: Methuen). -1967, The

Lore and Language of Schoolchildren (London: Oxford). Oxford Classical

Dictionary, 1970, ed. N. G. L. Hammond and H. H. Scullard, 2nd edn (London:

Oxford University Press). -1960, Gaudier-Brzeska,

A Memoir (1916) (Hessle, Yorkshire: Marvell Press). Puttenham, George,

1968, The Arte of English Poesie (1589) (Merston, Yorkshire:

The Scolar Press). Traugott, Elizabeth

C. and Pratt, Mary L., 1980, Linguistics for Students of Literature

(New York: Harcour:t Brace Jovanovich). |