|

|

|

Electronic Reserve Text-- from Lester Faigley, Fragments of Rationality: Postmodernity and the Subject of Composition Chapter 3: The Linguistic Agent as Subject MAXINE HAIRSTON'S 1982 proclamation of a "paradigm shift" claimed that the two allied disciplines motivating the new process paradigm were cognitive psychology and linguistics. By the end of the 1980s, one of these forces, linguistics, apparently had vanished. A noncontroversial aspect of Stephen North's controversial survey of writing research, The Making of Knowledge in Composition, is the omission of linguistics as an important disciplinary subfield. North does not even include language or linguistics in the index. Another classification of writing theorists and researchers presented by Patricia Bizzell at the 1987 meeting of the Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC) also fails to mention linguistics as a major line of disciplinary inquiry ("Forming the Canon"). |

|

|

One could argue that North and Bizzell erred either by leaving out linguistics or by subsuming it under a broader heading, and in support of this argument one could assemble a formidable group of North American researchers of written language, who in the 1980s applied principles and analytical tools developed by linguists.(1) Nonetheless, one could also easily defend the position implied by North's and Bizzell's classifications-that the influence of linguistics on the study and teaching of writing in North America has dwindled to such an extent that linguistics is no longer a major contributor of ideas. The demise of the influence of linguistics results not so much from the lack of substance in recent work on written language as it does from the lack of a dominant approach within linguistics that is applicable to the study of writing. Researchers of written language do not share common goals and methodologies, nor use the same terms, nor recognize common research issues, nor even agree about the nature of language. In spite of the brilliance of certain individual studies, the whole adds up to considerably less than the sum of the parts. The situation was much different in earlier decades of CCCC. In the 1950s

linguists were leaders in the organization and published articles frequently in its journal. The major conflict within CCCC was characterized as "correctness" versus "usage." with linguistics contributing research on language variation to counter absolute judgments of "good" and "bad" English. Donald Lloyd's call for a composition course built around linguistics in 1952 reflected the newly found tolerance for usage among the liberal wing of CCCC. Correctness again

became an issue following the publication of Webster's Third New

International Dictionary in September 1961, which set off a storm

of public controversy over its practice of basing descriptions of usage

and pronunciation on what people actually said rather than what experts

assumed to be correct. The much vilified editor of Webster's Third,

Phillip Cove was a featured speaker at the 1962 meeting of CCCC. More

important, however, was work in sociolinguistics arguing that dialects

considered prestigious or "standard" gain their status by

being identified with the wealthiest and most powerful groups in a society

and not from their inherent superiority. Sociolinguists denied assumptions

that speakers of "nonstandard" dialects are somehow deprived

or suffer from a cognitive deficit by demonstrating that nonstandard

dialects are as inherently logical as standard ones. A measure of the

authority given to sociolinguistics during this time came with the 1974

Students' Right to Their Own Language statement discussed in

the previous chapter, which lists 129 entries on dialects and the teaching

of writing in an attached annotated bibliography. [82] Lewis as an example of a semantically subordinate sequence of modifiers, each modifying the level above.

Using such examples as models, Christensen designed exercises that teach students to observe carefully and to describe accurately; he felt that practice in using nonrestrictive modifiers could generate the supporting detail that is characteristically absent from much student writing. In "Generative Rhetoric of the Paragraph," he used the cumulative sentence as a way of analyzing units of discourse larger than the sentence. Christensen believed that the paragraph is structurally a macrosentence, and he found intuitive evidence that the paragraph is structurally similar to the cumulative sentence from the fact that many of his cumulative sentence examples could easily be translated into paragraphs if the nonrestrictive modifiers were made into complete sentences. In successive issues of College Composition and Communication immediately following the initial publication of "Generative Rhetoric of the Paragraph" in 1965, Alton Becker and Paul Rodgers presented alternative views of paragraph structure. Becker proposed a semantic slot conception based on tagmemics, another variety of structuralism. He criticized Christensen's model for its lack of a semantic theory adequate to explain in formal terms the relationships Christensen perceived. Becker's criticisms were on the mark because no semantic theory existed at that time (nor does one exist today) that can account for these relationships. But by the same standard Becker's tagmemic alternative also lacked an elaborated semantic theory and it had less intuitive appeal because it presented only two basic paragraph patterns. Rodgers's criticisms of Christensen's analytical model of the paragraph were more substantial. He argued that the paragraph is not so much a semantic unit as it is an orthographic unit. Instead of the paragraph as the basic unit of discourse, Rodgers advanced semantic units that he called stadia of discourse (conceptual chunks of discourse, not often coincident with paragraph divisions). Considerable work followed in the 1970s from lines of research established in the 1960s, ineluding the continuation of the discussion of how coherence is achieved by Ross Winterowd ("Grammar") and extensions of Christensen's ideas to the essay as a whole by Frank D'Angelo, Michael Grady and Will Pitkin. But as these efforts grew in scope, their shortcomings became immediately apparent. Without an elaborated semantic theory, the structural classifications seemed too idiosyncratic and arbitrary, as well as too vague, to be the basis of pedagogy. [83] In the 1970s the

energy in the language camp within rhetoric and composition passed to

those interested in sentence combining, which grew out of the work of

Kellogg Hunt on syntactic development in the 1960s. Like others at the

time, Hunt was inspired by Chomsky's theory of generative grammar. His

suggestion that sentence-combining practice would enhance the syntactic

maturity of developing writers was demonstrated in several studies with

junior-high age children, most notably by John Mellon, in Transformational

Sentence-Combining, and Frank O'Hare. These findings were extended to

a college population in a major study at Miami (Ohio) University conducted

by Donald Daiker, Andrew Kerek and Max Morenberg, which concluded that

a sentence-combining curriculum could increase the syntactic maturity

and overall writing quality of first-year college students. At first

the researchers assumed that the gains were related (Daiker), but when

they analyzed the extent to which syntactic factors influenced readers'

judgments, they found that the measures were almost unrelated to the

assessments of quality (Kerek). But van Dijk's

ambitious project failed to provide adequately for the contexts in which

language is used, and after several attempts to augment his semantic

theory with pragmatic theory, van Dijk turned his attention elsewhere,

For those who continued to work in text linguistics, the scope of their

inquiry became more and more restricted. Even though there has been

much research on written language in the 1980s from both inside and

outside composition studies, no work has inspired the enthusiasm raised

by generative rhetoric and sentence combining, nor have their been any

large-scale movements within the discipline based on linguistic research. [84] discussed in linguistics

outside of North America in the 1980s, and there is much work now being

done on language and politics.

Before moving to how critical linguistics might have influenced the study of writing, I would like to reflect on why language study within composition declined so quickly. The obvious answer is that the influence of linguistics was swept away by the movement toward understanding and teaching writing as a process, but the process movement alone does not explain such a quick demise. For underlying reasons we must look to the discipline of linguistics itself. If we ask what happened within linguistics, again there is an easy answer: Noam Chomsky. Chomsky's theory of transformational-generative grammar influenced the study of language in North America as no other theory had in the past. Shortly after the publication of Chomsky's second major book in 1965, Aspects of the Theory of Syntax, linguists were either on board the fast Chomsky theoretical express or hopelessly behind on the slow, data-gathering local. For those in other disciplines interested in questions concerning language and discourse, generative grammar at First appeared to be a methodological breakthrough, a way of describing the messy data of language with orderly rules that could obtain universally. These researchers, however, soon encountered the limitations that Chomsky had been careful to anticipate. Language could be orderly only if it were idealized: if actual language was used as data, the orderliness of language predicted by generative grammar soon disintegrated. Chomsky insisted that language be viewed as abstract, formal, and accessible through intuition. His goal for a theory of language was describing a human being's innate capacity for language, not how people actually use language. When asked what relevance the study of linguistics had for education, Chomsky has consistently answered: absolutely none.(2) Gradually, those interested in studying discourse came to heed Chomsky's warnings. No matter how hard they tried, researchers could find no fruitful way of applying advances in formal linguistics for their own research programs beyond early language acquisition. Research in sentence combining as a [85] method of teaching

writing is a good case in point. Early sentence-combining experiments

developed from the concept of the "kernel" sentence in Chomsky's

initial presentation of transformational grammar in Syntactic Structures

in 1957. Students were given two or more short kernel sentences and

asked to combine them into one, using a particular transformation signaled

in the exercise. But by the time John Mellon published Transformational

Sentence-Combining: A Method for Enhancing the Development of Syntactic

Fluency in English Composition in 1969, the first report of a major

sentence-combining study, Chomsky had abandoned the notion of kernel

sentences. Soon "transformational" was dropped as an adjective

modifying "sentence combining." and research in sentence combining

proceeded independently of later developments in syntactic analysis. Before the rise of generative grammar, linguists were scattered in departments of anthropology, English, and other modern language departments. These linguists tended to share some of the interests of members of those disciplines, and the arrangement fostered interdisciplinary cooperation. The excitement that accompanied Chomsky's theory accelerated the formation and growth of separate linguistics departments committed to the theoretical study of structure in language. The methodology of generative grammar with elaborate sets of formal rules emphasized the difference of its project from those of other humanities and social science disciplines, as well as from other schools of linguistics. Theoretical linguists dismissed the questions of other disciplines such as those of language education as applied and "uninteresting." In their view, the only truly interesting questions in the study of language concern abstract universals underlying language. To blame Chomsky, however, for the decline of linguistics within composition studies is not merely simplistic: it is wrong. The limitations of generative grammar were demonstrated when stylistic studies aimed at analyzing the "deep structure" of style failed to produce results beyond what could be observed from surface features (for example, Ohmann, "Generative Grammars"). Nevertheless, researchers of language in written discourse did not cease working when they realized that generative grammar was not useful for their purposes. Rather, they encountered again and again a fundamental difficulty met by earlier linguists beginning with Zellig Harris, who in a boundary-breaking article in 1952 had ventured beyond the sentence. [86] When these linguists analyzed stretches of language larger than a sentence, they attempted to apply those criteria they had used for analyzing phonemes, morphemes, and clauses. In the tradition of American structural linguistics, they assumed that a continuum of formal correspondences exists between smaller and larger units. What many researchers in written language did not consider was that the basis of text structure might be radically different from that of sentence structure, that no one kind of structural description might be adequate to characterize text structure. Models of text structure based on a few patterns, such as those of paragraph theorists Christensen and Becker, at first were attractive but inevitably failed to account for a variety of distinctions that readers perceived among different texts. These models were confounded when readers encountered a paragraph where a topic sentence could not be readily identified, or when readers with different levels of familiarity with the subject matter of a paragraph could assign differing interpretations of what is important. Efforts to describe text structure have all been frustrated because texts--unlike phonemes, morphemes, and clauses--are semantic rather than structural units. Semantics has been the least developed area in American linguistics, as opposed to European linguistics, partly as a result of different readings of Saussure. American structural linguistics derived from Saussure a methodology that was well suited for describing the phonology of unstudied and often quickly disappearing languages. Because U.S. linguists grew up within the dominant ideology of behaviorism in the social sciences, they continued to make empiricist assumptions about language and ignored Saussure's discussions of meaning. European structuralists,

on the other hand, explored Saussure's proposal that since language

is a self-contained system, the boundaries for meaning, like those for

meaningful sounds or phonemes, are largely arbitrary. Following Roman

Jakobson's analysis of how differences in sound are grouped as distinct

phonemes according to shared articulatory features (Selected Writings),

several European linguists, including Louis Hjelmslev and A J. Greimas,

proposed a systematic analysis of semantics based on shared aspects

of meaning. The broadening of European structuralism to questions of

semantics led to an even more expansive use of structuralism to study

culture as a system Most American linguists avoided such extensions. Instead, they took the advice of Leonard Bloomfield, who argued in 1933 that language can be studied scientifically only to the extent that meaning is ignored. The Chomsky revolution did not overturn this bias from structuralism. Indeed, Chomsky has frequently argued (most recently in The Generative Enterprise) that linguists should not be concerned with semantics (though Chomsky claims that much [87] of semantics can be incorporated within syntactic theory). When North American theoretical linguists brushed against semantic issues, they used the same methodology devised for structural description of material features of language. Phonemes, for example, can be described in terms of their articulatory features. The English phoneme /b/ is distinguished from /pi by vibration of the vocal cords, a feature that linguists describe as "voicing" and represent with the notation <+ voice>. The logic of distinctive features was extended to semantics. The noun man might be described by the following distinctive features:

Such an analysis, however, is not going to account for why a speaker today who begins a talk before an academic audience with the sentence Every professor must deal with his students man to man, and who continues with a pattern of male pronouns to refer to students of both genders, risks alienating a large segment of the audience. The deficiency in formal semantics cannot be corrected by adding secondary connotative features. The problem is

one that Bronislaw Malinowski identified a half century ago. Malinowski

argued that language cannot be understood apart from the contexts of

its use. Meaning, therefore, cannot be described adequately in terms

of universal features but only in terms of specific functions in specific

contexts. Meaning can never be fixed in the way that models of text

structure imply they can, nor can hedges such as determining authorial

intent provide the firm ground for building models of text structure.

But American linguistics rejected the possibility that the basis of

language is meaning and that meaning is socially constructed. [88] experience or be activated from structures existing in the mind but can be preexisting in a culture. One of the classic statements of this position came in Roland Barthes's Mythologies (1957), where Barthes demonstrates that social meanings precede the perception of ordinary things, Many observers, however, trace the entry of this rich tradition of European structuralism into North American discussions of language as stemming from Roman Jakobson's paper, "Linguistics and Poetics," presented at the 1958 Indiana University Conference on Style. The issues raised by European structuralism were not new to everyone, however. One British linguist familiar with Malinowski and well aware of developments on the continent was T. R. Firth (1890-1960), who remains relatively obscure in the United States. One of the reasons Firth has been relegated to a far branch of the linguistic family tree is that many of his essays were first given as occasional papers, and at first glance they read like after- dinner speeches with their many local references. Within these essays, however, are passages that offer insights about language that only recently have scholars of written discourse begun to accept. Firth maintained that we are born individuals but that we become persons by learning language. I will quote at length from an essay first published in 1935: Every one of us starts life with the two simple roles of sleeping and feeding: but from the time we begin to be socially active at about two months old, we gradually accumulate social roles. Throughout the period of growth we are progressively incorporated into our social organization, and the chief condition and means of that incorporation is learning to say what the other fellow expects us to say under the given circumstances. It is true that lust as contexts for a word multiply indefinitely, so also situations are infinitely various. But after all, there is the routine of day and night, week, month, and year, and most of our time is spent in routine service, familiar, professional, social, national. Speech is not the "boundless chaos: Johnson thought it was. For most of us the roles and lines are there, and that being so, the lines can be classified and correlated with part and also with episodes, scenes, and acts.... We are born individuals. But to satisfy our needs we have to become social persons, and every social person is a bundle of roles or personae: so that the situational and linguistic categories would not be unmanageable. (28) Firth here sounds very much like Bakhtin's associate (and perhaps his pseudonym). V. N. Voloshinov, who speaks of a physical birth as an animal and a historical birth as a person (37), as well as Bakhtin's contemporary. Lev Vygotsky. While Firth's functionalist notion of the subject now has been challenged by the contradictory, decentered subject of postmodern theory, Firth did recognize that the dichotomies of individual/society and cognitive/social are false. He did not stop at theorizing but was equally concerned with the implica- [89] tions of a social view of language for systematic analysis. Firth believed there can be no one method of analysis adequate to explain meaning. In a later essay he wrote. "The statement of meaning cannot be achieved by one analysis, at one level, in one fell swoop" (184).

Firth's belief that social interaction is embodied in language was taken up by his students whose work collectively came to be known either as systemic or functional linguistics or by the combination. The most notable of these students is M.A.K. Halliday, who is best known in rhetoric and composition from applications of Cohesion in English, which he wrote with Ruqaiya Hasan. Cohesion in English attempts to define the concept of a text, an issue that has left those who would analyze texts open for attack on the charge they could not identify their object of study. The concept of cohesion, however, is only a small part of Halliday's larger theory. In Language as Social Semiotic. Halliday asks how people construct social contexts for language and how they relate social contexts to language. The key principle for Halliday and for others working in the Firthian tradition is function -- how language is actually used, not how it might be idealized as an abstract system. Following Malinowski's lead, Halliday theorizes that contexts precede texts, that words come to us embedded in the contexts where they are used, and that meaning is organized according to those contexts. He considers how people in different groups develop different orientations to meaning, advancing the concept of register to explain how certain configurations of meaning are associated with particular situations, ranging from relatively fixed registers such as the international Language of the Air. which pilots and navigators who fly internationally must learn, to more open registers such as the discourses of medicine. Other students of language familiar with Halliday's work were also influenced by the rise of the political Left in British universities in the 1970s, and soon they began exploring how systemic-functional theory might illuminate questions of language and politics. The manifesto for critical linguistics, a marriage of Marxism and systemic-functional linguistics, came in the 1979 volume Language and Control, written by four scholars who were then teaching at the University of East Anglia: Roger Fowler. Robert Hedge, Gunther Kress, and Tony Trew.(5) Their joint efforts proceeded from two assumptions in the Firth-Halliday tradition. First, language is functional in the sense that all language, written or spoken, takes place in some context of use, According to Halliday. "Language has evolved to satisfy human needs; and the way it is [90] organized is functional

with respect to these needs" (Introduction to Functional Grammar

xiii). Second, language is systemic because all elements in language

can be explained by reference to these functions: in other words, we

should conceive of elements of language as constituting an organic whole.

From these two assumptions, the East Anglian linguists inferred a third:

if the relationship between form and content is systematic and not arbitrary,

then form signifies content. The latter assumption brought these linguists

close to the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis that language determines thought.

But instead of working across languages as Sapir and Whorf did, they

worked within English, linking language use directly to social structure

and ideology.(6) Fowler and Kress argue that language is not simply a reflection of social structure nor is it independent. Rather, the influence between language and society is bidirectional. They write: "Language serves to confirm and consolidate the organizations which shape it, being used to manipulate people, to establish and maintain them in economically convenient roles and statuses, to maintain the power of state agencies, corporations and other institutions" (190). They call for a critical linguistics capable of analyzing the ..two-way relationship between language and society"(l90). The program for critical linguistics they envision is not aimed at "mining" representative structures out of language nor at isolating those features that typify a particular social group. Instead, the priority is reversed. Descriptive linguistics is used as a means for a larger social critique of unjust social relations. The project of critical linguistics is to engage in an unmasking of ideology or what Fowler and Kress call demystification. In another chapter Tony Trew shows how conservative newspapers transform events potentially disturbing to their ideology into "safe" readings. When white police indiscriminately shot blacks in the former British colony of Rhodesia (now Zimbabwe), the event was reported in the Times as a result of "tribalism" through a series of linguistic transformations. Another major difference between the East Anglia group of critical lin- [91] guists and earlier critics of language such as George Orwell lies in the scope of critical linguistics. Where Orwell pointed to lexical items such as pacipcation as examples of deceptive language, critical linguistics extends beyond syntax to the constraints of genre, which are often taken by linguists as well as writing teachers to be ideologically innocent. While the East Anglian project for critical linguistics does not provide a set of procedures for each analysis comparable to Walker Gibson's method for distinguishing "tough... "sweet... and "stuffy" styles, it does apply many of the methods of systemic-functional linguistics for investigating the cultural assumptions involved in unproblematic readings of everyday texts. To demonstrate how the critical linguistics project employs the tools of analysis Halliday developed. I would like to examine two texts I collected while I was a senior fellow at the National University of Singapore during the 1986-1987 academic year.

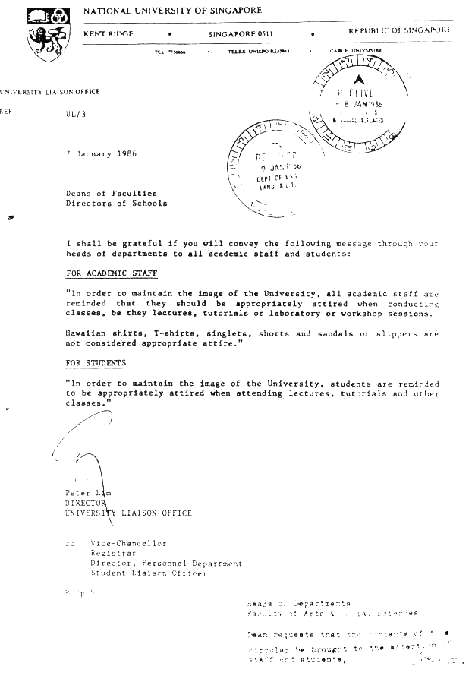

When I began teaching in Singapore in July 1986. 1 received a large folder from the university administration that included the usual kinds of general information given to new staff members such as a map of campus, a description of the library, and so on. The large folder also contained an assembled collection of twenty-three memos. These memos were dated as far back as 1976 to a few months before my arrival. After reading these memos. I assumed that the reason for including them in the folder was to communicate university policy to new staff members. For example, four of the memos warned faculty not to talk with the press without prior approval from the university. One of these memos concerning the university's dress code is reproduced as Figure I. Figure 2 is a copy of a newsletter sent to me by the headmaster of United World College of South East Asia, a private school that my then fifteen-year-old son attended while we lived in Singapore. The newsletter also deals with institutional regulation of clothing, but in some respects it differs from the university memo. Both texts are at times explicit about what kinds of clothing should not be worn. The university memo warns against wearing "Hawaiian shirts. T-shirts, singlets, shorts, and sandals." (The provision against Hawaiian shirts puzzled me, since batik shirts, which resemble Hawaiian shirts, are considered national dress and worn on formal occasions in Singapore. A veteran colleague explained to me that this provision was intended for a former member of the faculty who was particularly outspoken and fond of wearing Hawaiian shirts.) The newsletter declares that nonregulation blouses, shoes with colors other than brown, and sockless feet are illegal. Both the memo and the newsletter also have explicit primary and sec- [92] Figure 1

Figure 2

ondary audiences. Both address subordinates through intermediaries. The memo is addressed to deans, who are to inform subordinate department heads, who are to inform faculty who, in turn, are to inform students. The quotation marks suggest that the secondary transmissions from head to staff and staff to students are intended to be oral, that the memo literally attempts to place [94] words in the mouths of department heads and staff. It is a kind of public notice that, since its contents are announced to students, cannot be ignored. Students cannot plead ignorance of it, nor can faculty, who because they have read the announcement to students, can be accountable for the definition of appropriate attire for the faculty as well. The headmaster also addresses parents as intermediaries, urging them to make sure that their children are in compliance with school rules. He too presumes a secondary oral transmission of the rules from parents to students. But the differences between the two texts are more noticeable. The first is an internal memo from higher administration written on letterhead stationery in the formal style of other circular memos, including a reference number at the top. It bears official stamps of receipt at the dean's and department head's offices and the signed endorsement of the dean at the bottom with the directive to bring it "to the attention of staff and students." The newsletter, on the other hand, apparently is a less formal document. It is not printed on letter-head and identifies itself by a typed heading: "HEADMASTER'S NEWSLETTER TO PARENTS." The texts also differ in length. The newsletter is almost three times as long as the university memo. More interesting to this discussion, however, are specific linguistic differences and similarities. I will start by considering what some linguists call agency, the match between the language of the text and the actions being described in the text. The Fit of a text to the reality it depicts has been analyzed in different ways by linguists Charles Fillmore and M.A.K. Halliday. Halliday explores the phenomenon in far greater depth in his discussion of transitivity, a term that Halliday uses not in the traditional grammatical sense to distinguish verbs that take direct objects from those that do not, but rather a term to talk about how speakers and writers choose to represent their experience by selecting among the options available in the grammar of a language. Halliday's goal has been to explicate how ordinary language codes some extraordinarily sophisticated interpretations of experience. In An Introduction to Functional Grammar Halliday assembles his extensive work on transitivity. He analyzes transitivity in a clause as consisting of three components: the process itself, typically coded as a verb phrase: participants in a process, typically coded as noun phrases, and circumstances associated with the process, typically coded as prepositional phrases and adverbial constructions. Halliday describes as "congruent" clauses that code agents as subjects and processes as verbs in sentences such as Prisoners of war build the railroad to Burma. Halliday refers to clauses such as "The railroad pushed through to Burma" or "1947 saw the railroad reach the Burmese border" as being "cross coded": that is something other than an agent functions as the subject or something other than the underlying process functions as the verb. He labels these clauses [95] instances of "grammatical metaphor." The metaphor is not expressed exclusively in the personification of railroad or 1943 but also in the grammar, since the participants in the clause fill grammatical slots at one remove or more from an underlying semantic representation. Thus, when something other than the agent functions as the subject, the relationship between verb and process is likewise altered, creating a metaphorical displacement that changes the meaning of the entire clause. The university

memo starts with a sentence that is congruent: I shall he grateful if

you will convey the following message ... This opening, however, is

merely a formulaic expression, as it appears verbatim in other circular

memos from higher administration. The body of the letter lies in three

sentences, two directed to staff and one to students. The first sentence

of each of two sections begins with a phrase that serves as a justification:

In order to maintain the image of the University. After the comma we

find the subject of the sentence, which we would normally take to be

the agent. In all three sentences, the agents are not present. Each

sentence uses an agentless passive construction. We do not know who

wishes to remind university staff and students that they should be properly

clothed --whether it is Mr. Lim, higher administration as a collective,

or some other person. Critics of bureaucratic language from Orwell onward

have pointed to the use of the passive for concealing agents. Less recognized

is the subtle way the agentless passive shifts responsibility to the

noun occupying the grammatical subject slot-in this case, the students

and staff. The mood of the second sentence is declarative, but the modal should be indicates it is a command. If it were worded as a direct command in its most unmitigated form, it would read: I command all staff mem6ers to wear clothing that I consider appropriate. The actual wording is perhaps more polite, but removing agents, disguising actions, and obscuring relationships serves a more important purpose. The decisions of individuals can be questioned and negotiated, but the policies of organizations cannot be disputed if the process of making that policy is concealed. Notice too that the sentence Staff are reminded that they should he appropriately attired contains a projecting clause. It doesn't say Staff should be appropriately attired but Staff are reminded that they should be appropriately attired. The use of remind suggests that the policy is preexisting, that staff should [96] know about it,

even though the Hawaiian shirt provision was at least a new wrinkle

in the dress code. The second paragraph in the newsletter sets out the specifics of the dress code. The paragraph begins with the existential construction "There has been no change." Rather than, "The rules committee has not changed," or "I have not changed." The second sentence also employs a pseudo-parallel structure. The verbs are unchanged and are acceptable are in coordinate clauses that appear parallel, but if we supply the agent for the passive, the sentence reads. I have not changed the specifications. and only garments that tailors sew according to these specifications are acceptable to me. The two clauses are not grammatically parallel, but if readers take them as parallel, the makers of the rules become just as invisible in the newsletter as they are in the university memo. And like the university memo, the paragraph ends with commands coded as declaratives: All students will wear [97] brown footwear

All boys will wear socks. The use of the modal will is ambiguous because

it can be construed both as a command and as a prediction of a future

state-that the headmaster's declaration will become the new order. The issue is no longer students going without socks but one of heresy until students return to the orthodox. It is as if the dress code were handed down by God, and the students are blasphemers for not following it to the letter. At no point is

there any hint that the rules might be debated, that students might

be more comfortable not wearing socks in a city sixty miles from the

equator. The fourth paragraph offers a justification for the dress code, beginning: This school stands for something. Something is the vaguest noun possible in this sentence. In other literature, United World College claims to promote international understanding and world peace by bringing together students from over fifty nations. The second sentence reads: The uniform is a symbol of our commitment and esprit de corps Again the ellipsis is significant. Commitment to what? International understanding? World peace? If so, then how does the wearing of socks help to achieve these goals? The second member of the compound--esprit de corps-is more revealing, since it is a term for the morale of a disciplined military unit rather than a diverse group of young people from many nations. Linguistic theory

that attempts to relate language to social practice can [98] and the headmaster's newsletter are incomplete unless they take into account the specific historical circumstances in which these texts were produced and read. How institutional settings change the meanings of statements was recognized by J. L. Austin, who discussed a class of utterances called performative utterances that cannot be strictly true or false but instead are either felicitous or infelicitous. If someone says. "I pronounce you husband and wife." that utterance can be felicitous only when spoken by a specific person with specific institutional authority in a specific ceremony. The institution sets the conditions for the ceremony to take place by delegating authority to the minister or other person conducting the ceremony. Austin, however, did not attempt to explain the relations between institutions and acts of language, but rather analyzed such conditions as properties of language. Pierre Bourdieu

presents a different view when he calls the institutional distribution

of power symbolic capital. The relation of language and power within

institutions is part of Bourdieu's larger theory of practice set out

in his Outline of a Theory of Practice. Bourdieu extends the

concept of a marketplace to analyze the distribution of cultural and

symbolic capital as well as economic capital. Just as in economic markets,

those who have extensive cultural capital attempt to hold and enlarge

that capital, forcing newcomers to struggle for a share. Those who hold

the dominant positions in a culture and most of its capital wish the

status quo to be proiected as "natural" according to prevailing

systems of classification (164). The contrast between the statements of dress code from the university and the headmaster of United World College is in part the difference between doxa and orthodoxy. The writer of the university memo can mystify authority because authority is not being challenged. The sheaf of memos I received 99] when I began employment was a kind of institutional memory. The memo on dress was in the same folder as the map of the campus and other informative documents because it contained traditional knowledge-knowledge for which ordinariness represents an important dimension of political power. The headmaster, on the other hand, deals with extraordinary knowledge because the very raising of the topic of dress in a newsletter to parents focuses attention on the arbitrariness of the dress code. He must appeal for orthodoxy when students are actively subverting the dress code, and his accusing of blasphemy those students who violate the dress code is a predictable move in Bourdieu's scheme.

"Reading" Ideology

and bourgeois culture from the minds of the public. Napoleon for a time supported the philosophes but later turned against them, accusing them of being concerned only with ideas and thus giving the term ideology a negative connotation (Donald and Hall ix). Marx and Engels in The German Ideology reinterpreted this concept of ideology when they argued that ideas do not determine social relations but rather they derive from social relations. Marx's and Engels's materialist interpretation separates their definition of ideology from other efforts to "unmask" ideology. The "base-and-superstructure" version of ideology in its "vulgar Marxist" form has the economic base determining directly or indirectly the ideological superstructure.(10) The most famous metaphor for this notion of ideology comes when Marx and Engels compare the mechanism of ideology to a camera oscura that produces an upside-down image. Of the world when workers accept the ruling class's version of the world. In the twentieth century, the "base-and-superstructure" model of ideology has come under heavy criticism, even from Marxist theorists. One of the most influential Marxist theorists on this issue has been Antonio Gramsci, who grants relative autonomy to the superstructure. Gramsci includes in the notion of ideology what he calls "practical political consciousness, fragmented, contradictory, and incomplete sets of ideas that people use to get on in the world. He directs his attention to those ideologies that are broadly held and apparently spontaneous -- ideologies he refers to as "organic." Many other twentieth-century theorists have offered a more neutral version of ideology, using the term as a synonym for "systems of belief" or "systems of thought" (for example, Clifford Geertz's frequently read essay. "ideology as a Cultural System"). This "systems-of-thought" notion of ideology is found also in Language and Control where Hodge. Kress, and Jones define ideologies as "sets of ideas involved in the ordering of experience, making sense of the world" (81). The "systems-of-thought" notion of ideology is implicit in Halliday's social semiotic view of language, but the Hallidayan view gives language a very active role in coding experience and in mediating social meanings.(11) This notion of ideology presents two major kinds of difficulty for the project of critical linguistics. First, it does not contain a theory for social critique. Second. it does not presume a determinism between language and thought. Halliday is careful to place language as one of several higher-order semiotic codes, and he makes it clear that it is not adequate to stop at language if one wishes to investigate larger cultural issues. The first difficulty is relatively easy to address. Critical linguists directed their attention toward asymmetries in relations of power that could be related to language. The second difficulty, however, is not so readily overcome, and early work in critical linguistics tended to take the deterministic view that dominant groups manipulate language to maintain their power over subordinated groups. [101] The lack of elaboration on how ideologies are implicated in social relations left an imbalance of attention on linguistic form, According to Fowler and Kress, among the most rewarding methods of examining a text is to consider the effects of transformations, in particular, nominalizations and passivizations. They offer the following example: In the middle of a report of the wreck of the oil supertanker Amoco Cadiz which happened towards the end of March 1978-the wrecked ship was in the process of breaking up, and oil spilling, at the time the newspaper went to press-the Observer gives the information "French moves to slap drastic restrictions on super- tanker movements have been dropped after British intervention... The nominalizations "moves" and "intervention" have the effect of obscuring the times at which these actions took place, and the newspaper's attitude to them. (2001 While Fowler and Kress warn that there is no critical routine through which a text can be run, they claim that certain kinds of linguistic analysis such as the unpacking of transformations frequently prove to be "revealing"(l98). The implication of these analyses is that the less transformed or more congruent version in Halliday's terms is closer to reality. In another book, Language as Ideology (1979), Kress and Hedge attempt to appropriate Chomsky's generative grammar for analyzing ideology in language, introducing an odd blend of mentalism and materialism. They claim explicitly that "the typical function of transformations is distortion and mystification, through the characteristic disjunction between surface form and implicit meanings" (35). The problem with

this assumption might be illustrated with another set of examples. Below

are sections from two articles that concern the issue of abortion. The

first article, "Abortion, Ethics, and the Law, by Claudia Wallis,

is from the July 6, 1987, issue of Time magazine, Although Time

does include editorials by guest columnists that take particular stands

on controversial issues, this article comes from the news sections and

is a presumably objective report on the legal status of abortions. The

second article, "New Questions--Same Old Debate" by John Cavanaugh-O.Keefe,"

appeared in the April 25. 1987, issue of America. a magazine

published by the Roman Catholic church, The article is labeled Op Ed.

an abbreviation for "Opinion Editorial." indicating that the

author will take a stance on an issue. Because the article is published

in America, the author also makes certain assumptions about his readers.

He takes for granted that they are opposed to abortion, and he also

assumes that they are familiar with recent battles over doctrine within

the Roman Catholic church. (from Time) [102] weeks younger) has long preoccupied people on both sides of the abortion debate. If medicine can save the life of an immature fetus, how can society allow the termination of an advanced pregnancy? When does the constitutional obligation to protect a potential citizen begin? How are the fetus's interests weighted against the mother's right to liberty and privacy? (Wallis 82) (from America) What is their

response? Their answer too is "No." Is it possible to justify

that refusal? How? It seems clear to the rescue teams that arresting and removing them is cooperation in abortion. If the police refuse to arrest, nobody dies. If they make arrests, children die. Their actions are necessary, though not sufficient, to kill those children at that location with that machine. (Cavanaugh-O'Keefe 335) The language in the article from America by Cavanaugh-O'Keefe is less transformed than that of the article from Time by Wallis, but I doubt that the East Anglian group of critical linguists would call the Cavanaugh-O'Keefe article less ideological than the Wallis article. Cavanaugh-O'Keefe says it is regrettable that some people do not classify a fetus as a person, but he is not concerned with convincing them that abortion is morally wrong. Instead, he addresses those Catholics who agree with him that abortion is wrong. He sets out a hypothetical example where police who believe that abortion is morally wrong are asked to arrest protesters at an abortion clinic. Then he poses the moral dilemma directly: "if the police refuse to arrest, nobody dies. If they make arrests, children die." Most of his sentences are congruent. Participants are for the most part represented in the text or readily inferred. The Wallis article, on the other hand, is heavily laden with nominalizations. [103] The phrase "termination of an advanced pregnancy" has hidden participants. Someone terminates and something is terminated. And pregnancy itself is not an object but a process with participants. Other nominalizations are more difficult to analyze such as "constitutional obligation." Someone is obligated to do something according to the Constitution or by power of the Constitution. These relationships are extremely complex since what exactly "Constitutional obligation" means in a particular instance has been debated inside and outside courtrooms for two centuries. The inclusion of sentences that are grammatically metaphorical invokes the reader~ acceptance of the present situation where abortions are legal under certain circumstances. Cavanaugh-O'Keefe

wishes to overturn the present situation. He recognizes that the struggle

over a woman's right to an abortion is a struggle over meanings. What

Wallis calls an immature fetus," Cavanaugh-O'Keefe calls an innocent

person," "unborn babies," "unborn children,"

"children," and a "member of the human family."

But on the issue of a mother's right to liberty and privacy" raised

in the Time article, Cavanaugh-O'Keefe is silent. The only mention of

women is an image of "mothers" seated nervously in the waiting

room of an abortion clinic. The analysis of these examples raises some of the limitations of the East Anglian proposals for critical linguistics, in spite of these limitations, the East Anglian group involved linguistics directly in confronting relations of domination--the critical dimension in Marx and Engels's analysis of ideology. At the same time, they brought to the study of ideology a means of showing how linguistic structures mediate ideology and how ideology can be analyzed in expressions heard and read in daily life. Where critical linguists quickly ran into trouble was in privileging linguistic form. They neglected that different readers interpret and use texts differently, that resistant readings are possible. and that texts themselves contain many contradictions and silences.(12) Now Hedge and Kress admit they underconceptualized social relations in their earlier work. In the preface to Social Semiotic (1988), Hedge and Kress write: In Language as Ideology we had recognized and assumed the importance of the social dimension, but even so we had accepted texts and the structure of language as the normal starting point for analysis. We now see social structures and processes, messages and meanings as the proper standpoint from which to attempt the analysis of meaning systems. (vii) [104] To emphasize the

separation of their current work from their earlier work, Hedge and

Kress now avoid using the term critical linguistics to describe their

current project. In Social Semiotics they do not give up on their

goal of analyzing how "dominant groups attempt to represent the

world in forms that reflect their own interests" (3), but they

maintain that the revival of semiotics is the best hope for providing

an analytic practice of how meaning is

In North America certain Hallidayan concepts used in critical linguistic analyses have become familiar in composition scholarship, primarily through the work of Joseph Williams. In 1979 Williams published an important essay, "On Defining Complexity." which questions the desirability of increasing the complexity of student's written syntax-the central assumption of sentence-combining pedagogy Williams argues that this goal is benighted, citing as evidence writing programs for professionals on the job that attempt to encourage simpler styles or "to undo what sentence combiners want to do" (598). Williams was not the first to question whether we should encourage students to write more complex sentences. A decade earlier Francis Christensen attacked sentence combining for promoting the wrong kind of growth - growth that he asserted would lead to "the lumpy, soggy, pedestrian prose that we justly deride as jargon or gobbledegook" ("Problem" 575). (13) What distinguishes

Williams not only from other critics of sentence combining but also

from other reformers of adult prose such as Rudolph Flesch is Williams's

move toward defining complexity in terms other than polysyllabic words

and T-unit or sentence length. In "On Defining Complexity."

Williams extrapolates from Fillmore's concept of case grammar, where,

similar to Halliday's notion of transitivity, a semantic representation

is theorized to underlie grammatical structure. Williams draws on psycholinguistic

research to make the claim that the dearest style is the one that is

most easily processed. [105] maxim: "in the subjects of your sentences, name your cast of characters. In the verbs of your sentences, name the crucial actions in which you involve those characters" (9). The first example revision in the book demonstrates this principle:

Williams uses

these two sentences as touchstones of bad and good prose. He describes

sentence 1 as "turgid, indirect, unclear, impersonal, wordy, prolix,

obscure, inflated, pompous." and sentence 2 as "clear, direct,

concise, flowing, readable" (8). High moral ground for the agent-action style is also claimed by Richard Lanham, whose Revising Prose and Revising Business Prose have become popular trade books as well as college textbooks. Like Williams, Lanham announces himself as a crusader against bad writing. He lumps traditional targets of stylistic reformers into a single foe, which he refers to as "The Official Style", Lanham claims all dialects of The Official Style suffer from the same imbalance:

[106]

Also like Williams, Lanham advances the clear style as a moral as well as a pedagogic issue. He accuses The Official Style of deadening our sense of ourselves: "The moral ingredient in writing, then, works first not on the morality of the message but on the nature of the sender, on the complexity of the self, "Why bother?" To invigorate and enrich your selfhood, to increase, in the most literal sense, your self consciousness"(l 06). Lanham promises that improving your verbal style will not only make your prose more lively but also extend the benefits to your person: "You will become more alive"(ll5). M.A.K. Halliday also writes extensively on agency in Spoken and Written Language (1985). He presents sets of examples similar to those of Williams and Lanham:

Unlike Williams and Lanham, however. Halliday does not claim that sentence 4 is better than sentence 3. Instead, he offers these examples as typical of the difference between written and spoken language. Halliday sees a characteristic difference between written and spoken language in the way each achieves complexity. Written language, according to Halliday, is lexically dense in comparison to spoken language. Spoken language, on the other hand, is typically more intricate in its syntax in presenting similar spans of ideas. Halliday illustrates this point with the concept of lexical density. Lexical density is the ratio of lexical items (often referred to as content words) to the number of clauses. He offers a hypothetical comparison between a sentence in a written text (sentence 5 below) and a spoken equivalent (sentence 6). Double bars mark clause boundaries, and brackets identify the embedded clause in (6):

The written version (sentence 5) contains twelve lexical items in one clause. Thus its ratio of lexical density would be twelve. The spoken version has ten lexical items according to Halliday's count (which omits do) and five clauses (not counting the embedded one). Dividing ten lexical items by Five clauses gives a lexical density ratio of two in the spoken version. This brief example [107] illustrates Halliday's

claim that "written language is corpuscular and gains power by

its density, whereas spoken language is wavelike and gains power by

its intricacy- ("Language and the Order of Nature" 148). He

is well aware that much written language resembles spoken language by

this definition, and that some speakers can talk in "written.'

language. What Halliday views as important is that the development of

written language brought a complementary process of interpreting experience,

All lexical items with the exception of bodies and move in sentence 7 are located in prepositional phrases, Halliday argues that it would be very hard to write the sentence without prepositional phrases and nominalizations: indeed, he maintains that many concepts in science and technology could not be expressed without nominalizations. Nominal structures are the necessary building blocks for constructing new claims on the basis of what is known and accepted. Furthermore, Halliday notes that nominalizations are vital for the thematic structure in English. In English sentences we expect the beginnings of sentences to give us a point of departure, what is called the theme in linguistic literature. In the Newtonian system functions as the theme in sentence 7. referring to some phenomenon that the reader is presumed to be aware of. Halliday describes the theme as a "peg on which the message is to hang," 173). These pegs are frequently nominalizations and prepositional phrases, Halliday's discussion of transitivity likewise extends beyond Williams' and Lanham's prescriptive advice. In Style: Ten Lessons in Clarity and Grace, Williams too acknowledges that nominalizations can at times be useful. and he includes in later chapters the relationships of old" and "new Information (the "theme/ theme" distinction) and of topics and comments. i' These additional principles, however, are mapped onto the first. The yardstick for measuring good writing remains the degree of adherence to an agent-action style, which Williams's own prose emphatically demonstrates. In his textbook, Williams's insistence [108] on supplying agents for his sentences forces him to use frequently the editorial we Instead of writing Verbs should agree with their subjects. Williams adds the agent: "We expect verbs to agree with their su6jects" (202). Sentences of this kind are abundant in Style: "Given what we've learned about problems of topic and stress, we can see the problem …" (108): "Sometimes we awkwardly split an adjective …"(138): "We can maintain a smoother, unbroken rhythm …"(139). Williams's exercises for students encourage them to use the same strategy for an exercise that asks students to revise poorly written examples. Williams offers in the answer section in the back of his book the revision (sentence 9) for the bad example of sentence 8:

Notice that the

changes in sentence 9 come as a result of inserting we into the text:

We have written…because we are attempting …whom we have hired. "Attempt"

is changed to are attempting, but other nominalizations (technical directives,

employees of little education, guidelines) are not similarly unpacked.

If we had Halliday's equivalent in spoken language, it would likely

be much longer and much more grammatically intricate than the four clauses

of the revised sentence. Williams's revision is not a categorical shift

from a written to a spoken style nor from a nominal" to a "verbal"

style. Rather it is a shift in perspective from an impersonal "These

directives are written" to a more personal "We have written

these directives." But the personal we is complex. The we who wrote

the directives may or may not be the same we who has done the hiring

in accordance with federally imposed guidelines. In a "strong" culture, employees identify with the corporation and its values. As a result, "employees know how to behave most of the time" (15). Because "they feel better about what they do... they are more likely to work harder" (16). Frequent use of we in the texts of a corporation is one of many strategies for encouraging employees, identification with the corporation. Interestingly, however, the use of we in Williams's revision I sentence 91 is [109] not the corporate

we in the sense of referring to everyone who works for a company. In

the revision we excludes those employees who were hired as the result

of "guidelines imposed on us by the federal govcmment..' In this

case "we" apparently contrasts the existing staff from those

who get hired as a result of equal opportunity programs. From a single

example, I do not want to claim that Williams's textbook is covertly

racist, but it does suggest that Williams's stated goal of sharing the

"power, prestige, and privilege that go with being part of the

ruling class" is unlikely to be achieved simply through writing

in an agent-action style. just as was the case in my earlier analysis

of articles from the abortion debate, an a highly nominal style, agent-action

style is not less ideological than

The spirit of Ferry and Teitelman's critique is admirable, but the solution of passing plain-language laws to address a multitude of problems associated with legal language is now seen as inadequate. Another attorney, David Cohen, attacks the assumption that consumers are homogeneous, arguing that plain-language contracts and other legal documents may be of most help to those who already are most informed. Being able to read the lease is not much comfort for those who can't pay the rent.

The critical linguistics movement was an important attempt to transcend disciplinary boundaries, and while its shortcomings were soon pointed out, it brought to abstract discussions of ideology specific examples of how ideolo- [110] gies are reproduced and transmitted: it brought to linguistic analysis considerations of reception as well as production: and it succeeded in taking the political analysis of language far beyond the Orwellian critique of lexical items such as pacification. More important to current projects in writing research, it problematized linguistic analysis by challenging the division between language and society and by demonstrating that texts are sites of social conflict. But the critical linguistics movement also demonstrates the limitations of linguistic theory in general for dealing with issues of conflict. While critical linguists attacked the refusal of sociolinguists to discuss the political implications of communities" such as speakers of American Black English, critical linguists did not skeptically analyze the notion of community itself. Instead, they analyzed language communities into groups of the dominating and the dominated--a division that Mary Louise Pratt finds characteristic of utopian projects, one that would subsume various lines of difference within one difference. The limitations of critical linguistics also demonstrate the difficulties of mapping the social onto structural links or grids and analyzing positions on those grids. Critical linguistics attempted to identify subjectivity with grammatical agency, but later its key figures heavily qualified this association Subject positions are occupied with different degrees of investment; there is no way of being certain, for example, that the headmaster who wrote the dress code newsletter is not parodying the discourse of educational authority while at the same time deploying it. The tools of linguistic analysis can be useful in analyzing how subject positions are constructed in particular discourses. The notion of subjectivity itself, however, is far too complex to be "read off" from texts. It is a more complex notion than that of "roles" because it is a conglomeration of temporary positions rather than a coherent identity: it allows for the interaction of a person's participation in other discourses and experiences in the world with the positions in particular discourses: and it resists deterministic explanations because a subject always exceeds a momentary subject position. In the next chapter I will examine how analyses of subjectivity might be used in analyzing the subject positions privileged in writing classrooms. |

|

|

Notes to Chapter 3 2. Chomsky repeated

this caveat most recently in an interview in April 1990 (Olson and Faigley).

However, he did suggest that the principles and parameters approach

which he initiated in lectures given at a conference in Pisa, Italy,

in 1979, may indeed be the linguistics revolution that others attributed

to earlier versions of generative grammar. 3. Newmeyer charts a diminishing of Chomsky's influence, seeing its nadir in 1970 at the high point of generative semantics only to recover dramatically with the introduction of the principles and parameters approach. Another pervasive influence toward formalism in the 1980s has been the association of linguistics and artificial intelligence. The demand for increasingly sophisticated parsers has directed attention toward aspects of language most amenable to formal analysis. Notes to Pages

86-104 4. At the same

time Chomsky was disposing of structuralism in American linguistics,

the semiological version of structuralism associated with literary theory

and anthropology rose in France led by Roland Barthes (Elements of

Semiology) and Claude Levi-Strauss. The resulting confusion helped

further to divide linguists from literary scholars, since the former

viewed the latter's embrace of structuralism as a backward step. 5. Hodge and Kress

later moved to Australia and have continued to collaborate on the critical

analysis of communication (see Social Semiotics). Fowler remained

at East Anglia and returned to his earlier work in literary study. Richardson

provides a helpful review of the East Anglian proposals for critical

linguistics and objections to those proposals. Fairclough includes critical

linguistics in Language and Power, his] 989 introduction to "critical

language study." 6 Another neo-Whorfian

position developed at the same time in radical feminist critiques of

language in North America and in Britain. These critiques maintain that

the possibility of nonsexist language is an illusion. Adrienne Rich

writes that when women "become acutely, disturbingly aware of the

language we are using and that is using us, we begin to grasp a material

resource that women have never before collectively attempted to repossess"

("Power" 247). The problem women encounter using language

is not simply a matter of the more familiar features of sexist language

such as the use of male pronouns to refer to people in general. Instead,

patriarchy is embedded in the ways language interprets the world. The

term motherhood typifies patriarchal control of language for Rich and

other radical feminists. Dale Spender in Man Made Language argues that

many women experience neither joy nor fulfillment in motherhood and

consequently feel themselves inadequate because "their meanings

do not mesh with the accepted ones" (54). That motherhood can only

be used positively reveals one way language helps to maintain unequal

relations of power between men and women Radical feminists claim that

when women use male-controlled language, they either falsify their own

experience or fall silent. 7. For an explication

of similar tactics in the writing of scientists, see Gragson and Selzer. 8. Notice too the

we in the embedded clause, we all have more important things to do.

In the first paragraph we refers to staff and students at V.W.C. In

this clause we refers to staff and parents. By shifting the referents

of we, the headmaster subtly reinforces the mutuality of parents and

school as agents of authority. 9. Thompson discusses

other works of Bourdieu that analyze the relation of language and power

in Studies in the Theory of Ideology, chap. 2. 10. Whether Marx

maintained this view throughout his life has been much debated. Several

arguments have been made that Marx adopted a less reductionist view

in later works. See, for example, Donald and Hall xv-xvi. 11. In this respect

Halliday's view of language as social semiotic has parallels with Foucault's

analysis of discursive practices in The Archaeology of Knowledge. 12. See Kress, "Discourses, Texts, Readers," for self-criticism of the earlier critical linguistics position.

14. See Colomb and Williams for discussion of the linguistic traditions on which Williams draws in Style: Ten Lessons. |