|

|

|

Electronic Reserve Text: Edward Finegan, "Linguistics," from: Joseph Gibaldi, ed., Introduction to Scholarship in the Modern Laguanges and Literatures. New York: MLA. 1992 LINGUISTICS has been called the most scientific of the humanities and the most humanistic of the sciences. Using both humanistic and scientific modes of inquiry, it is a field that defines languages and Language as its domain. The term languages--with a small l--denotes particular symbolic systems of human interaction and communication (e.g., English, Spanish; Korean, Sanskrit). Language--with a capital L--refers to characteristics common to all languages, especially grammatical structure. While some linguists consider Language the proper domain of the field, most study particular languages and view the field broadly. All language varieties-that is, all dialects (standard and nonstandard, 'regional and national) and all registers (written and spoken, from pidgins to poetry and from motherese to legalese) contribute equally to our knowledge of languages, and every variety is equally shaped by the laws of Language. For some linguists, languages are quick studies in the social structures of human communities and the mainstay of social interaction; for others, Language is primarily a window on facets of the mind. For all, languages and Language are puzzles whose patterns are not yet adequately described, let alone explained, in social or psychological terms or, indeed, in neurological or biological terms. |

|

The principal objects of linguistic investigation are the structural properties

of languages and the variation in linguistic form across communities,

situations, and time. Ideally, the goal of linguistics is to account for

both the invariant and varying structures of languages, for language acquisiton

and language change, and ultimately to provide an account of what links

language structures and the communicative, social, and aesthetic uses

to which they are put. As Deborah Tannen writes, "Linguistics can

be scientific, humanistic, ,and aesthetic. It must be, as we are engaged

in examining the eternal tension between fixity and novelty, creativity

within constraints" (Talking 197).

A central concern of linguistic analysis is grammar. Grammarians focus on the structural characteristics of languages and, often, on universal grammar, which encompasses the principles and structures common to all grammars. Following nineteenth-century comparative and historical linguists, modern structuralists treat grammars as autonomous systems and view them abstractly, independently of their communicative functions, their social contexts, and their aesthetic deployment. Typically, structural grammarians analyze sentences and [4] parts of sentences

rather than discourse or texts, and they do so strictly in terms of

form. Another major focus of linguistic analysis is language use, particularly the ways in which linguistic structures reflect and sustain social relations and social situations. Linguists interested in language use focus on structural variation and seek to explain differences by examining communicative and situational contexts and the social relations among participants. They take discourse rather than sentences as their domain, in part because the choice of a structure (e. g. , active voice over passive voice or the pronunciation of ,in over ,ing) cannot be explained without reference to the discourse and context of that structure. Discourse can be spoken, written, or signed, of course, and it can be produced by interacting interlocutors (as in conversation and interviews) or by solitary speakers or writers with specific addressees (as in personal letters) or generalized addressees (as in radio broadcasts and scholarly articles). A pair of examples may help clarify matters. Structural grammarians aim to characterize the relation between active, voice sentences ("The author persuasively argues the thesis in a dazzling central chapter. ") and passive voice sentences ("The thesis is persuasively argued by the author in a dazzling central chapter. "); their work focuses on the arrangement of syntactic elements within the sentence and on the formal relation between active and passive structures (a topic to which I return later). Structural grammarians do not ask which contexts favor one form over the other 'in a discourse. Functional grammarians (one type of linguist interested in language use), however, account for the choice between actives and passives by appealing to such phenomena as parallel structures in successive sentences, the linear organization of given an9 -new information, and textual coherence. In functional analyses--for instance, of the syntactic and distributional patterns of over four hundred relative clauses ("the car that she borrowed") transcribed from tape-recorded conversations--researchers typically conclude that their findings strongly support

As the second example, consider the variant pronunciations of English -ing words like studying. Structural linguists would note that -in' and -ing are alternative pronunciations having the same referential meaning (failin' an exam is no less painful than failing one). Sociolinguists (with their focus on language use) would note that, while all speakers use both these forms, they do so with different proportions of the variants, depending on their social filiations and the context of their discourse; even within a small strip of conversation, a single speaker may say both -ing and -in'. Sociolinguists aiming to uncover the patterns [5] linking -in' and -ing to social groups and social situations have found in Norwich, England (Trudgill, Social), and New York City (Labov) that women use more -ing pronunciations than men and likewise that people with higher socioeconomic status use more -ing pronunciations than people with lower socioeconomic status do in comparable situations. Thus, -in' and -ing are social dialect features because they mark gender and socioeconomic status; they are characteristic of particular social groups. These same variants of pronunciation also index situations of use in Norwich and New York, with -ing occurring more frequently in formal situations than in informal ones. This variation across situations makes these pronunciations register features as well as dialect features, and it is curious that the same variable marks both speakers and situations, especially since such joint functioning of linguistic features seems to be the rule rather than the exception. Similar patterns of distribution characterize other features in these and other English-speaking communities, and features of other language communities function in much the same way. Social stratification of linguistic variables is known in Argentine and Panamanian Spanish, Brazilian Portuguese, the French of Montreal and of Lyons, and in several German speaking communities. Interaction between social dialect variation and register variation probably can also be found in these communities, as in Norwich and New York. Such interrelated patterning between social dialect and register variation challenges sociolinguistic theorists to provide an explanation. (See Baron in this volume.) Because the myriad shapes of human languages--from Swahili and Sioux to French and Finnish-must conform to the constraints of the human language faculty, the explanation for the existence of between four and six thousand languages and countless dialects, as well as for the disparate forms of, say, dinner-table conversation and an epic poem, must lie outside the uniform character of the brain. It is a truism that an infant capable of acquiring anyone language is equally capable of acquiring any other; after all, no physiological characteristics predispose one to the acquisition of a particular language. Rather, a body of contingent facts--when and where one is born and with whom one is raised; the complex social, economic, political, and religious history of one's community molds the particular language and dialect one acquires. An adequate linguistics must account for both the variant and invariant structures of languages, as well as for their use as indexes of social groups and communicative situations. Otherwise, as Dell Hymes notes, we fail to see what communities. have achieved. within the realm of possibilities delimited by the brain's language faculty (see Foundations). THE SUBFIELDS OF LINGUISTICS There are many frameworks for language analysis, and, though individual analyses are faulted for eclecticism, the field of linguistics is itself eclectic. One

observation that drives much current grammatical theorizing is the stunning efficiency and uniformity with which children acquire a native tongue, and speculation abounds on the contributions of nature and nurture-the roles played by the hypothesized innate language structures of the brain and by the social and cultural contexts of acquisition, including the "input" available to children. (On language acquisition and language learning, see Kramsch in this volume.) Like the authors of certain linguistic treatises of seventeenth...century Europe, grammarians today are struck more by similarities across languages than by the obvious but superficial differences between languages, and much current theory addresses aspects of grammar that are thought to be common to all languages. Such language universals, if they prove to be innate, could explain the efficiency and uniformity of first...language acquisition. Thus the aim of many linguists is to design a model of the representation of language in the mind, delimiting the universal features of grammatical structure and characterizing the parameters that could lead to actual and potential differences across languages; that is, these linguists strive to provide a characterization of the notion "possible human grammar." Other linguists have different goals, and grammar is only part of what they aim to account for. For these linguists, grammatical analysis that does not consider what communities make of their language is too limited and mechanistic; they argue that formal, autonomous grammars overlook socially and humanistically significant variation within and across communities. This difference in viewpoint, which currently divides the field of linguistics, is captured in the dichotomy between grammatical competence and communicative 'competence. For Noam Chomsky, grammatical competence is "the speaker-hearer's knowledge of his language" (Aspects 4). Echoing Ferdinand de Saussure's distinction between langue and parole (see his Course), Chomsky distinguishes between competence and performance (more recently between "internalized" and "externalized" language). Although earlier he seemed principally to want to exclude slips of the tongue and other errors from linguistic description by relegating them to performance, his exclusions ignore far more than errors. For Chomsky, externalized language is language as it exists in utterances and discourse, as it can be observed in use. Internalized language, in contrast, is a property of the mind or brain, and thus it cannot be observed directly: it is "some element of the mind of the person who knows the language, acquired by the learner, and used by the speaker...hearer" (Knowledge 22). Chomsky's linguistics excludes real... world language: language in use (externalized language) "appears to play no role in the theory of language"; indeed, "languages in this sense are not real...world objects but are artificial, somewhat arbitrary, and perhaps not very interesting constructs." Linguistics, for Chomsky, treats only internalized language, and in that sense it is "part of psychology, ultimately biology" (Knowledge 26-27). Of course, many linguists regard language use as the basis for all that is known of language, and they view language variation as an essential part of the competence of speakers and a legitimate object of linguistic analysis. Linguists |

||

| [7]

In an alternative conceptualization, John J. Gumperz and Dell Hymes define the object of linguistic analysis--in marked contrast to Chomsky's grammatical competence--as communicative competence: "what a speaker needs to know to communicate effectively in culturally significant settings" (vii) For these linguists,

Linguists who focus on communicative competence "deal with speakers as members of communities, as incumbents of social roles, and seek to explain their use of language to achieve self...identification and to conduct their activities" (vi). For the student of literature, communicative competence is of greater concern than grammatical competence, which focuses only on sentences and fails to address discourse. But grammatical competence is also important for literary analysis because verbal art exploits the same grammatical structures as other language varieties. If Chomsky's views were not popular, it would go without saying that an adequate conception of language must attend to both, grammatical and communicative competence. Within these broad approaches, most linguists pursue relatively narrow goals in their research, often within one of the numerous subfields of linguistics. Some of these subfields reflect particular levels of grammatical analysis such as sound systems and syntax, while others reflect distinct methodological approaches such as acoustic phonetics and computational linguistics. Still a third set combines different objects of analysis with different methodologies; these include historical linguistics, sociolinguistics, psycholinguistics, and discourse analysis. Grammatical analysis has held center stage in linguistic analysis for millennia (but compare Lunsford's comments in this volume concerning the historical importance of rhetoric). Today grammar treats sounds and their patterning (phonetics and phonology), the organization of semantic and grammatical elements within words (morphology), the arrangement of words into structured strings (syntax), and the complex systems of lexical and sentential meaning (semantics). Between grammar and use is the subfield of pragmatics, which treats the relation between linguistic form and its contextualized use and interpretation in communicative acts.

Historical linguistics, the nineteenth-century springboard for modem linguistics, uses a variety of methods to trace the evolution of languages and relate them to one another "genetically." It employs two principal models: the family-tree model (in which offshoots of parent tongues evolve over time) and the wave model (which reflects the influence of languages on one another when they are in contact). From the family-tree model we understand Latin to be the historical predecessor (the parent language) of Spanish, French, Italian, Portuguese, and Rumanian, among others, and we see Proto-Germanic (of which we have no records) to be the parent of English, German, Dutch, Norwegian, Swedish, Danish, and the defunct Gothic, among others. From the wave model we understand the influence of French on English after the Norman invasion in AD 1066 and of the neighboring Baltic languages on one another in the Baltic. sprachbund (borrowed from the German word for "speech league"). Historical linguistics has provided knowledge of the Indo.. European family of languages, including the Germanic, Italic, Hellenic, and Celtic branches on the one side and the Slavonic, Baltic, Indo.. Iranian, Armenian, and Albanian branches (as well as the extinct Anatolian and Tocharian) on the other. It has also given us a grasp of other language families and established the genetic independence of languages sometimes thought to be related (e. g., Chinese and Japanese). Much work remains to be done in identifying the genetic relations among the native languages of Africa, the Americas, Australia, and Papua New Guinea and in distinguishing between inherited and borrowed similarities. Despite the central role of historical studies in the development of linguistics, the subfield does not now enjoy the prominence it once did (see Watkins). Still, the last decade has witnessed an exciting revival of valuable historical work even on languages as well combed as English and French. Much of this new work falls into one of four broad approaches: it reanalyzes earlier stages of a grammar in the light of what is now understood about structure, typology, and universals (on English, see the works by Kroch and Lightfoot; on Romance, see those by Fleischman and Harris); it applies current models of social dialect and register variation to the competing forms of earlier periods in an effort to explain change

(see Weinreich,

Labov, and Herzog; Biber and Finegan; Romaine, Socio-historical);

it seeks to establish general patterns of'semantic development in grammati...

cal and lexical forms' (see Traugott; Traugott and Heine); or it traces

the grammaticalization of forms arising frequently in the discourse

patterns of conversation (see Hopper; Givon; Traugott and Heine). Sociolinguists have a wide spectrum of interests, including urban dialects, ethnic and socioeconomic language varieties, gender...related language characteristics, register variation and. stylistics, the ethnography of communication, and traditional dialect geography. More than a few sociolinguists pursue applied interests, including literacy; and the relation between forms of discourse and their uses in political and social control (see Baron in this volume; Andersen; Gee; Macdonell). Situational variation and stylistics are also gaining increased attention from sociolinguists. As the complex relation between dialects and registers is addressed, sociolinguists and .literary scholars are likely to find their shared interests growing. Discourse analysis, sometimes considered part of sociolinguistics, is a loosely defined subfield that has no specific methodology. By definition it focuses not on sentences but on texts, socially and contextually framed. As Tannen says, discourse analysis "does not entail a single theory or coherent set of theories [nor does it] describe a theoretical perspective or methodological framework at all. It simply describes the object of study: language beyond the sentence." For Tannen, as for many linguists, the name "discourse analysis" says "nothing more or other than the term 'linguistics': the study of language" (Talking 6-7). But, as we have seen, not all linguists agree that language beyond the sentence is the proper domain of the field, and discourse analysis has a separate name and identity in part to legitimate certain types of language analysis and to encompass sociological and anthropological work on language. Despite Tannen's equation of linguistics and discourse analysis, it is principally discourse analysis that has brought attention to texts and to context (see Greetham and Scholes in this volume). In conclusion, a few words about semantics and pragmatics: Semantics has from time to time been ruled in and out of linguistics. In the first half of the century, structural grammarians like Leonard Bloomfield argued that including semantics would entail the study of all knowledge and thereby threaten linguistics as an independent discipline. Today semantics is defined narrowly and viewed as part of grammar, which is after all a system relating sound and meaning. Falling within the purview of semantics are the structure of the lexicon and the elements of lexical meaning, as well as the ways in which the meaning of a sentence is not merely the sum meaning of its words. Pragmatics mediates semantic meaning and contextualized interpretation. A sentence like "Can you pass me the salt?" is semantically a yes-no question concerning the ability of the addressee to pass the addressor the salt, but its contextualized interpretation will likely be as an indirect request of the addressee to pass the salt to the speaker, and pragmatics explores the mechanisms of such [10] interpretation. Besides studying such indirect speech acts, pragmatics looks at a wide range of sociolinguistic matters, from the expression of politeness and the use of respect vocabulary to conversational structure and performative utterances (those that in specifiable conditions effectuate what they say: "You're under arrest"; "I now pronounce you husband and wife"). The subject matter of pragmatics includes investigation of the situations in which performative utterances accomplish their work and of the manner in which interlocutors understand the intended force of an utterance (see Levinson for a useful survey). PREMISES OF LINGUISTIC ANALYSIS Before we consider

the structural levels of language, several widely accepted premises

of linguistics are worthy of mention. First, most linguists recognize

that linguistic symbols are essentially arbitrary-that no inherent relation

exists between things and their names in various languages. The word

for "cat" differs from language to language, and so do the

words for-the vocal noises cats make, though an occasional hint of a

culturally filtered echo inhabits words like: meow. The same arbitrariness

might be claimed for the order of events in the world and the order

of linguistic expressions representing them, although rhetorical strategies

may favor sequences of expressions that mirror actual chronology, as

in narratives. Even so, to say that linguistic symbols'" are essentially

arbitrary is not to say that they lack iconicity altogether. The child

who reports, "My mother is taking a long, loong, looong shower,"

reflects the intuitive value of iconic expression as much as the poet's

crafted onomatopoeia does. But despite increasing recognition of iconic

elements in word and clause formation, the essential arbitrariness of

basic linguistic symbols remains intact. (For recent work on syntactic

iconicity, see Haiman.) Second, linguistics aims to be a descriptive field, not a prescriptive one. Linguists describe the structures of human language and the uses- to which those structures are put; they do not (as linguists) prescribe what those structures ought to be in some ideal world or judge their use in the real world. In fact, linguists have been belligerently neutral on questions of language value. (On descriptivism and prescriptivism, see Baron; Finegan; and Milroy and Milroy.) Third, since Saussure in the early twentieth century, linguists take description of a language at one point in time (synchronic description) to be basic to all other analysis. Historical (or diachronic) analysis with its focus on language change compares two or more synchronic descriptions. Diachrony, like synchrony, can focus on texts or sentences or words or sounds, and it can appeal for explanation to factors that are structural, psychological (e.g., perceptual), or social (e. g., language contact). Synchrony cannot appeal to diachrony for explanation, though history can often shed light on how the facts that need explaining came to be as they are. [11] Phonology. Not all the sounds of a language are structurally significant in that language (i.e., not all differences of sound will signal a difference in meaning). A given pair of sounds existing in two languages may represent different structural units in one language but not in the other. Thus both English and French have oral and nasal vowels, but nasalization cannot signal a difference in meaning between two otherwise identical English words, whereas in French it can (and does). For example, English has a rule that nasalizes vowels when they precede nasal consonants (written m, n, ng). Compare the pronunciations of lamb, ban, bong with lap, bad, bog. Because vowel nasalization is regular (.Ii. e. , rule-governed) in English, the occurrence of a nasalized vowel is predictable (i.e., any vowel preceding a nasal consonant will be nasalized), and thus nasalization cannot serve to differentiate words. The-nasalization rule makes it impossible for English to have a pair of words such as bam and bam or late and lote, where only the first of each pair has a nasalized vowel. In French, however, nasalization is not rule-governed; rather, it is a feature of individual words that can signal a meaning difference in contrasting pairs such as [5t] and [~t] (honte 'shame'; hotte 'hutch'). (Don't be misled by the spelling: children acquiring French have no spelling to guide them!) Nasalization, then, is a significant feature of French, capable of making a contrast between words. Children (and adults) learning French must note, in their mental dictionaries, nasal and oral vowels for each word (lin [le] 'flax' is not the same as lait [le] 'milk'), whereas an English...speaking child systematically nasalizes vowels by rule and doesn't need to identify nasalized vowels word by word. Another example is provided by English and Korean, which both have the same three oral consonants articulated by closure of the lips: the aspirated p of pill (pronounced with an audible breath of air, strong enough to blowout a match, and represented phonetically as [ph]), the unaspirated p of spill (represented as [p]) , and the b of bill (represented as [b]). These three articulations have only two representations in the mental lexicon of English speakers (i. e. , as Ipl or /b/). The aspirated [ph] of pill does not need to be distinguished from an unaspirated [p] in a speaker's lexicon because all English speakers have internalized a rule that aspirates every Ipl that begins a word (as well as Ip/' s in certain other positions; the same rule also aspirates It I and Ik/ sounds in parallel positions). But no conceivable rule could specify whether Ipl or Ibl occurs in an English word. Therefore Ipl sounds and Ibl sounds must be distinguished from each other English word by English word. In Korean, by contrast, the occurrence of aspirated [ph] and unaspirated [p] is not determined by rule, so speakers must note for each word whether it has [ph] or [p]. The occurrence of [b] in Korean, however, is rule governed: [b], but never [p], occurs between vowels or other voiced sounds (and hence [b] could never occur at the beginning or end of a word). [12] Thus, Korean and English 'subsume the same three sounds in two structural units of their phonological systems, but they do so quite differently. In English, the units are [p] and [b], with [ph] and [p] merely rule...governed variants of Ip/. In Korean, the units are [p] and [ph], with [b] merely a rule...governed variant of Ip/. In other words, English attaches significance to whether a consonant is voiced (like [b] and [z]) or voiceless (like [p] and [s]), but it treats aspiration as insignificant. Korean attaches significance to whether a consonant is aspirated or unaspirated but treats voicing as not significant. As a consequence, English can have the 'words bill and pill (the latter with rule-assigned aspiration), but itndoes not have pill without aspiration (as pronounced in spill). Korean distinguishes phul 'grass' from pul 'fire'; it has pap 'law' and mubap 'lawlessness' but could not have mupap because of the rule that voices Ipl between vowels. Learners of a foreign language tend to transfer their native distributional patterns of rule-governed variants to the target language; thus, an English speaker learning French is heard to pronounce Pierre and petit with the aspirated [ph] that English (but not French) uses at the beginning of a word, while a French learner of English may fail to provide the aspiration to words that begin with Ipl in English. This tendency to apply the phonological rules of one's native language to another language is part of what creates a foreign accent. In sum, languages have inventories of significant phonological units (phonemes) such as [p] and rules for generating required but nonsignificant "phonetic" variants. Distinguishing underlying "emic" units from "etic" realizations is at the heart of structural linguistics, and the notions of "emic" and "etic," which have been borrowed into folklore and anthropology through the work of Claude Levi...Strauss, constitute part of the definition of structuralism in other fields. (For more on the cross...disciplinary use of linguistic constructs, see Gunn in this volume.) Every language also has constraints on how consonants and vowels can be joined to form syllables. Japanese, for example, has three basic syllable types. If C represents a consonant and V a vowel, Japanese permits V and CV syllables (e.g., a and ga), as well as CVC syllables provided that the second consonant is a nasal (as in hon 'book'). English, by contrast, permits not only V, CV, and CVC syllable types but also syllables beginning with two consonants (plate and grit) and three consonants (as pronounced in split, stream, and squid). With three consonants, however, the first must be /s/; the second /p/, /t/, or /k/; and the third /l/, /r/, or /w/. English permits many other syllable types, including rela... tively complex ones like CCCVCCC representing words like squirts and squelched (where ch represents a single consonant sound and ed represents [t]). Renewed interest in syllables has contributed to a new "metrical phonology." With its focus on stress patterning and other rhythmic phenomena, metrical phonology has reawakened interest in literary uses of meter and rhythm among linguists (see Kiparsky and Youmans). Morphology and Morphosyntax. At a level higher than sounds and syllables, grammars make reference to morphemes, which are sequences of sounds

associated with

a meaning (DOG, SEE) or grammatical function (third-person singular

present"tense marker"s as in sees or progressive marker "ING

as in seeing). Unlike a desk dictionary, whose entries are typically

words, the mental lexicon of a speaker also lists morphemes (many of

which, like DOG, SEE, and KANGAROO are likewise words). As the speaker's

counterpart to a published dictionary, a mental lexicon has entries

that lack etymologies and illustrative citations but specify certain

other information about a morpheme: which phonemes it contains and in

which order (as a basis for pronunciation), semantic information (for

meaning), and syntactic information about word class (part of speech)

and which classes it can co"occur with (e. g., plural "s affixes

to nouns but not to adjectives). For a verb, the lexicon contains information

about its syntactic" semantic frame; for example, give, as in "Alice

gave Sarah the book," takes three noun phrases (or "arguments"):

an agent giver (Alice), a patient given (the book), and a recipient

(Sarah). Much remains to be discovered about how men" tal lexicons

are organized so as to make their contents accessible for online sen"

tence production and comprehension: obviously the alphabetical organization

of dictionaries is neither available to speakers nor adequate for such

purposes. As it happens,

much of the information needed to structure grammatical sentences could

be specified either in the lexicon or in the syntax of a speaker's grammar.

In just which of these components particular information actually resides

remains unclear in many instances. Like traditional grammatical analyses,

recent theory favors placing a greater burden on the lexicon, with a

consequent reduction in the complexity of the syntactic component. This

theoretical shift has made morphology and morpho syntax major subfields

of grammar. Generative Syntax.

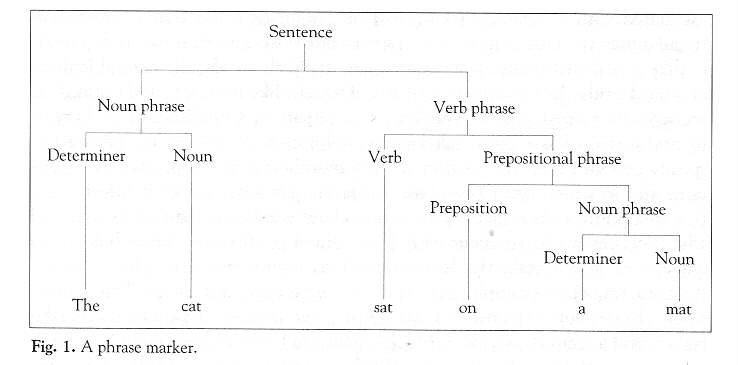

For the past three decades, the most influential ways of characterizing

sentences structurally have employed a "generative" approach,

whereby a lexicon and a set of rules for organizing its elements into

the sentences of a language can be specified explicitly (i. e., mechanically,

computationally, autonomously-without reference to contingent facts

about the world or the particular situations of use). Although phonological,

syntactic, and semantic components of generative grammars have been

recognized for some time, each component has been viewed as part of

a unified, integrated system. Thus, the syntactic component generates

a structure that receives an interpretation for meaning by the operations

of the semantic component and an interpretation for pronunciation by

the operations of the phonological component. In this standard generative

model, the syntactic component is the centerpiece. It comprises a lexicon

of the sort described above and a set of phrase"structure rules

of the general form S ~ NP VP (i.e., a sentence consists of a noun phrase

followed by a verb phrase). Phrase"structure rules generate deep

(or underlying) structures known as "phrase markers" (the

familiar "tree diagrams," illustrated in fig. 1). As figure

1 shows, phrase markers specify a linear order of constituent elements

(determiner precedes noun), as well as a hierarchical order (prepositional

phrase has two constituent parts, preposition and noun phrase). [14]

|

||

|

[15] potential values are innately specified. If this conception of grammatical structure is correct, it will go a long way toward explaining the breathtaking accomplish.. ment represented by every child's first-language acquisition. Generative grammarians

using the government..binding model have pro.. posed a set of modules

as alternatives to the unified system of rules and transfor.. mat ions

of standard transformational grammar. One module treats case assignment

(not the morphological cases familiar to students of inflected languages

like German, Russian, or Latin but a highly abstract case system); another

module assigns semantic roles to nouns; a third handles government.

For exam.. pIe, the earlier English passive transformation, as Chomsky

later decomposed it (Lectures), consists of four procedures: moving

the object noun phrase following the verb to the subject position preceding

it, moving the initial subject noun phrase to a position after the verb

and making it the object of the added preposition by, altering the verb

to a past participle, and inserting an appropriate form of the auxiliary

verb to be. Serious problems

occur with such a transformation, however. For one thing, as formulated,

the English passive is unrelated to passive constructions in o-ther

languages. More important, permitting such specific transformations

would license other similar transformations in the model, thereby granting

grammars extraordinary power and freedom. Because acquiring a language

is easier when fewer options are available to the child acquiring it,

generative theories favor the most limited grammar compatible with the

facts. Space restrictions here preclude a description of how passives

would be treated in current generative models, but the English..specific

points in the transformation above have been relegated to individual

lexical items and are no longer handled by the syntax. Significantly,

too, passive structures are not generated by specific movement and insertion

procedures, as in the'standard transformational analysis. Instead, various

general principles applicable to all languages operate independently

of one another to "license" certain structures, and the confluence

of various mod.. ules c,an produce passive structures (see Jaeggli). The modular approach

to grammar arose partly because early transformational grammar was largely

English..based, and it assumed that what held true of English would,

mutatis mutandis, hold true of all languages. But as grammarians turned

to French, Spanish, Italian, Dutch, Japanese" Chinese, and other

Ian.. guages, much of the putative generality of English..based analyses

crumbled, and many middle..level generalizations fell (including the

notion of structure..specific and language-specific transformations)

and were replaced by general principles of wider applicability. As a

result of these theoretical realignments, current grammatical descriptions

are declarative rather than procedural, and they rely heavily on the

features of individual verbs and nouns as specified in the mental lexicon. Related to the subject of linguistic generality is typology, and a few words about typological approaches may be useful. Typologists are interested in shared patterns of structural features that are independent of language contact

and of genetic relatedness among languages. If, say, English, German, Dutch, Danish, Norwegian, and Swedish exhibit certain characteristics that don't appear in other languages (e. g., dental suffixes to mark the past tense, as in English thanked and German dankte), these features may (as in this case) be inherited from a common ancestor language and, as such, be germane to genetic relat, edness but not necessarily to typology. Likewise, in the Baltic sprachbund mentioned earlier, Greek, Rumanian, Albanian, and Bulgarian share a number of structural features, although they belong to different branches of Indo, Euopean, whose member languages do not generally possess those features. One such feature is the loss of the infinitive such that, instead of expressions like "give me to drink," these languages have the equivalent of "give me that I drink": Greek "~os mu na pjo," Albanian "a,me te pi," Bulgarian "daj mi da pija," and Rumanian "da-mi sa beau" (examples from Comrie, World's 10). Rumanian does not share this feature with the other Romance languages, nor does Bulgarian share it with the other Slavonic languages, nor Greek with Ancient Greek. Instead, the similarities arise from mutual contact among neighboring languages, and therefore they are not of direct interest to typologists. Even independently of contact and genetic relatedness, significant correIa, tions among structures exist across languages-for example, between the order of objects and verbs, on the one hand, and of other constituents such as nouns and adjectives, on the other. In languages where the verb follows the object (OV languages, such as Japanese and Persian), there is a strong tendency for adjectives, genitives, and relative clauses to precede nouns and for prepositions to follow them (in which case they are called "postpositions"). In languages with the complementary pattern in which objects follow verbs (VO languages, such as Welsh, Irish, and Classical Arabic), nouns tend to precede adjectives, genitives, and relative clauses, and there are prepositions. Japanese is a canonical OV language" with all the expected patterns: adjectives and relative clauses preceding nouns (omoshiroi hon 'an interesting book'; anata ga katta hon 'the book you bought'); genitives preceding nouns (Taroo no hon 'Taro's book'); and postpositions (Tookyoo ni 'to Tokyo'). Other languages are less canonical. English is mixed, with relative clauses following their head nouns and with prepositions, as expected for VO languages, but with adjectives generally preceding nouns ("subversive intent"), a characteristic of OV languages, while genitives can precede or follow ("Auden's apologies" and "the modernity of Emerson"). The relations among such word...order patterns, universal grammar, and the parameters of individ, ual languages constitute a central puzzle for syntactic typology. Functional Syntax. Before leaving syntax and typology, I return briefly to functional grammar, which highlights certain (fundamental empirical and philosophical issues remaining unsettled in linguistics today. One fundamental empirical question that suggests the depth of the disagreement is the concept of sentence. As axiomatic as the idea seems in most current (and traditional) grammar (compare the phrase marker of fig. 1), some functional grammarians [17]

The philosophical issues involve the disputed status of innate grammatical structures cast in the image of the seventeenth..century rationalists. As suggested above, generative grammarians posit innate grammatical structures whose puta.. tive configuration has changed somewhat in response to changing theoIetical models but whose bedrock Cartesian notion of innate knowledge remains stable. For the functionalists, however, grammar is emergent rather than innate; it is the (developmental and evolutionary) product of discourse created in particular communicative contexts. These competing ideologies, as Paul Hopper has noted, correspond to the two major intellectual currents of the day: structuralism "with its belief in and attention to a priori structures of consciousness and behavior" and hermeneutics "with its equally firm conviction that temporality and context are continually reshaping the elusive present" (133). Semantics. As important and central to language as semantics is, sentence semantics can barely be mentioned here, while lexical semantics can only be named. Besides their grammatical relations within a clause as subject, object, and indirect object, noun phrases' have semantic roles such as agent, patient, instrument, recipient, locative, and temporal (see Fillmore). In "Alice gave Eric the prize in Atlanta yesterday," Alice is an agent, Eric a recipient, prize a patient, Atlanta a locative, and yesterday a temporal. Such semantic roles do not have fixed connections to grammatical relations: not every agent is a subject, nor is every object a patient. In English, grammatical subjects can have any of several semantic roles: as agent in "The jailer opened the gate with the key"; as instru.. ment in "The key opened the gate"; as patient in "The gate opened"; as locative in "Maine suffers extremes of hot and cold"; and as temporal in "Tuesday is our busiest day." English is exceptional in permitting such a wide range of semantic roles as subjects. Many other languages, including even close relatives like German, permit fewer semantic roles as grammatic,al subjects, and the direct equivalents of certain sentences given above would therefore be ungrammatical in those languages. SOURCES OF LINGUISTIC DATA As a consequence of different focuses and subfields, preferred sources of linguistic data also differ. Field work involving elicitation sessions with bilingual or mono.. lingual speakers of the language being analyzed is a classic source of data for grammatical, lexical, and phonological data. Supported by gestures and simple

props, elicitation sessions consist basically of questions and answers, and they produce phrases, clauses, and sentences, rather than discourse, as data. For some linguists, introspection suffices; they ask themselves and others about the grammaticality of imagined (and sometimes farfetched) sentences. For still others, natural-language texts, from historical records to transcribed conversations, serve as data. Narratives, an important source of discourse data, are available in many forms. For naturally occurring speech, portable audio and video recorders make it possible to gather data anywhere, from African villages and Native American reservations to urban street corners and suburbrn shopping malls, and it can be collected by formal or subtle interview techniques or by participant observation. Psycho linguists, especially those interested in sentence processing, construct experimental situations in which consultants (sometimes unwittingly) perform linguistic tasks that provide special data. To investigate language acqui.. sition, some linguists engage in lengthy and detailed taping and transcription of children's discourse, while others use little more than introspection and logic. Thus linguists take as data any form of written, spoken, or signed language, whether naturally occurring or elicited; and some linguists, especially those in the generative framework, take intuitions and judgments of grammaticality as data. Linguists working with various sources of data have been called field linguists, bush linguists, armchair linguists, street linguists, and so on. Because particular sources of data are naturally skewed in one direction or another, each source needs to be supplemented by others, for only when complementary sources of data produce compatible findings can investigators be confident ab,out the validity of their analyses, as William Labov has noted. STANDARDS AND STYLES, REGISTERS AND DIALECTS Standard languages

and dialects are familiar notions to readers of this volume. From a

historical point of view, standard languages are simply dialects that

h'ave undergone certain processes of standardization, whereby a designated

dialect is elaborated in form to meet an expanded range of functions

and is then codified in dictionaries and grammars. The standardized

variety is used in the legal, medical, educational, and other professional

affairs of a nation, as well as in the mass media. Linguists reject

the folk view that nonstandard dialects are corruptions of the standard

variety and instead view all dialects of a language (including the standard

variety) as descendants of a single ancestor tongue, the standard. simply

being the variety selected-for political, social, economic, and other

nonlinguistic reasons for development as a vehicle of wider communication,

especially in writing. The concept of

register is less familiar than that of dialect, and it can be introduced

by considering multilingual speech communities, whose linguistic repertoires

comprise varieties drawn from several languages. In multilingual communities,

particular languages tend to serve particular domains of use: one |

||

| [19]

language in the home, another in business or education, a third in religious ceremonies (e.g., Yiddish, English, and Hebrew among older New York City Jewish families; Spanish, English, and Latin among Latinos in Los Angeles thirty years ago). Thus, within multilingual communities marked linguistic variation can exist from situation to situation. The same is true in monolingual communi.. ties, which also mark different communicative situations with different language varieties. The term registers refers to language varieties characteristic of particular situations of use, and the linguistic features of those registers reflect the communicative, situational, and social circumstances surrounding their use. At the very least, a change of topic (e.g., from the national pastime to the national debt) will necessitate a change in vocabulary, but registers can differ from one another in as many ways as languages differ, though less strikingly, of course. Registers are less studied by linguists than dialects are (and they are often less salient to speakers), although some registers (e. g., motherese, legalese, conversation, and advertising) have been thoroughly analyzed (see Ferguson; Crystal and Davy; Levi and Walker; Ghadessy). Linguists' registers

are akin to literary. analysts' genres, but the two are not altogether

equivalent. Although the genres of literary language, from a linguistic

point of view, are not different in principle from other registers,

literary language has received special attention from linguists (see

Freeman; Jakobson; Kiparsky; Leech and Short; Pratt; and Sebeok; see

also Culler in this volume). Approaches differ: some linguists analyze

prose fiction, others poetic verse; some treat syntax, others meter;

and so forth. One recent approach to English prose style tracks functionally

related sets of linguistic features in fiction, essays, and letters

over the past four centuries and finds parallel evolution in all three

registers (Biber and Finegan). For example, just as first..person and

second..person pronouns, interrogative sentences, contractions, hedges

(e. g., sort of, kind of), and several other linguistic features characterize

conversation and tend to co..occur fre.. quently in that register but

not in, say, typical academic articles, so other sets of linguistic

features co..occur with .regularity in other kinds of discourse (see

Biber for details). Three such feature sets have been associated with

literate versus oral styles, where literate means characteristic of

typical written styles but does not necessarily entail writing (e. g.,

scholarly monographs and lectures) and oral means characteristic of

spoken styles but does not necessarily entail speech (e.g., conversations

and personal letters). [20] example, with respect to informational versus involved purposes, texts typically show relatively frequent use of one set of defining features or the other but not both. In the historical study of English fiction, essays, and letters mentioned above, the linguistic features representing three dimensions were tracked: informational versus involved purposes, explicit reference versus context dependence, and abstract versus concrete style. Because the frequencies of the defining- features of a dimension determine a characterization of each text along that dimension, texts of any period and any register can be compared with those of other periods and registers. The past four centuries have witnessed a drift of English fiction, essays, and letters from relatively explicit, or "elaborated," to relatively more context-dependent, or "situated," reference, as shown in figure 2 (where solid lines show average values for each century and the length of the vertical bars represents the range of texts) [21] This drift reflects, among other things, a decrease in the number of relative clauses and nominalizations (e. g., establishment, sincerity) and an increase in the number of time and place adverbs that characterize texts of these registers. Note in figure 2, however, that the eighteenth century bucks the trend and exhibits more explicit referencing strategies (i.e., more elaboration) than the seventeenth century does. While some eighteenth-century writers advanced the trend toward more situated forms of reference in fiction and letters, others (staunch neoclassicists like Samuel Johnson) wrote prose works with higher levels of elaborated reference than writers of the preceding or the two following centuries did. The other two dimensions, which are not illustrated here, display the same overall patterns: prose moved from relatively more informational to relatively more involved and from relatively abstract to relatively nonabstract. In sum, the patterns along all three dimensions indicate that English prose has become increasingly "oral" since the seventeenth century, although eighteenth-century prose was on average exceptionally "literate."

Linguistic analysis has thrived on dichotomies, oppositions, contrasts; the field has exhibited a tendency to see things in black and white, as "either/or" rather than "more or less." But the dichotomies of the past are proving inadequate to accommodate the depth and range of observations confronting linguists now, and a recent trend has been to analyze language more in terms of "squishes," of tendencies instead of absolutes, and to view language forms along parameters of continuous variation. Tightly constrained models (e. g., dichotomies between grammatical and ungrammatical structures or between speech and writing) fail to accommodate observations of actual language use. In this connection, the use of computers has had two notable effects on linguistic analysis. .On the one hand, computers show clearly how inadequate many rules of grammar really are: when programmed into a completely obedient and perfectly dumb computer, the output of such rules is quite feeble compared with natural discourse and is often ungrammatical. On the other hand, when large bodies of text are analyzed by computational techniques, the continuous variability of language along multiple situational dimensions becomes more comprehensible, the patterns behind the data less opaque.

[22] capital L), of

discounting differences among languages and dialects and ignoring the

contingent effects of history and cultural evolution? Is it what we

as human beings share linguistically that joins us in the human community,

or is humanity equally defined by the ways in which communities differ

from one another? Alternatively, what are the implications of giving

prominence to contingent factors, to existing and potential social structures,

to examining discourse as empowering or disenfranchising? Is rhetoric

merely the dress of thought, or are languages and thoughts mutually

implicated? Some linguists believe that Language must first be studied

acontextually, in an idealized state analogous to the physicist's vacuum.

Others are persuaded that a linguistics devoid of context and a view

of Language devoid of variation do violence to the social nature of

languages and shunt aside questions of social justice and of epistemology,

ignoring the role of languages as primary instruments of social construction

and shared, knowledge; further, autonomous views of grammar clearly

tend to ignore verbal art and leave it with an impoverished linguistic

foundation. This essay expresses the viewpoint that language is essentially social and essentially psychological and that neither languages nor Language can be understood without attention to both. The grammatical representations that underlie language use surely reside in the brain and will one day be given a neurological account. Just as surely, the neurology of language has taken form under the influence of the structures and functions of social intercourse. Presumably (some would say "obviously") communication and social interaction have helped Language evolve into its current shape in the brain, languages and dialects evolve into their myriad forms across speech communities, and registers develop to meet the peculiar challenges of an endless array of communicative situations. For today's linguistics to focus exclusively on either one or the other of these fundamentally important aspects of language would certainly limit progress in the field as a whole. For any branch of linguistics to attempt to define the others out of court would be shortsighted, if not foolhardy.

The World's Major Languages, by Bernard Comrie, is a useful reference work, containing chapters on forty languages, including Spanish, French, Portuguese, Italian, German, Dutch, English, Russian, Japanese, Chinese, and Arabic; each chapter provides useful information about the structure of the language and its writing system, as well as something of its history and social setting; Comrie has separately collected those chapters treating the major languages of western Europe, while Martin Harris and Nigel Vincent have collected and augmented the chapters on the Romance languages. Peter Trudgill's Language in the British Isles covers English in various aspects and the Celtic languages (which are not covered in Comrie), as well as Channel Island French, Romani, and others. Charles A. Ferguson and Shirley Brice Heath provide coverage of American Indian lan- |

||

| [23]

guages (which are

not treated by Comrie); New World Spanish; other languages used in the

United States, including German and French; and the registers of law,

medicine, and education. Geoffrey Leech and Michael H. Short take a quite different approach to stylistics than that of Douglas Biber and Edward Finegan illustrated in this chapter; Leech and Short focus primarily on the qualitative, whereas Biber and Finegan mix quantitative analysis and qualitative interpretation. Roger Fowler gives a useful introduction to stylistic issues, while Michael Toolan, analyzing Faulkner's Go Down Moses, also includes informati~e chapters on the current state of stylistics. Reflecting a 1958 symposium at which Roman Jakobson deliv... ered extensive closing remarks on poetics and stylistics, Thomas A. Sebeok's Style in Language remains a classic collection of essays, while Donald C. Free... man's volume includes more recent pieces. Paul Kiparsky and Gilbert Youmans offer a collection of original articles on rhythm and meter. Gunther Kress's

essay is a brief review of critical discourse analysis; the works of

both Roger Andersen and Diane Macdonell exemplify critical language

studies at greater length; Tony Crowley applies critical techniques

to the notion of standard English. Kenji Hakuta's Mirror of Language

and Suzanne Romaine's Bilingualism are good on bilingualism. Deborah

Tannen's Linguistics in Context is a wide...ranging and accessible collection

of lectures on humanistic approaches to linguistic analysis delivered

in 1985 by various scholars at institutes sponsored by the Linguistic

Society of America, Teachers of English to Speakers of Other Languages,

and the National Endowment for the Humanities. The excitement of the

debate between autonomous grammarians and functionalists is palpable

in a special issue of Language and Communication (ed. Harris and Taylor).

In The Politics of Linguistics, Frederick J. Newmeyer defends an autonomous

view; Terence Moore and Christine Carling are critical.' Also critical

is Claude Ha... gege's Dialogic Species, a best...seller in France,

now available in an English translation. On discourse analysis, the

works by Deborah Schiffrin, Michael Stubbs, and Teun van Dijk are all

useful. John Haiman's collection records the proceedings of a 1983 symposium

on iconicity in syntax. [24] topic; John A.

Hawkins makes typological comparisons between German and English. Beyond

basic texts, Linguistics: The Cambridge Survey, edited by New' meyer,

is recommended, although some of its essays are of moderate difficulty.

Andersen, Roger.

The Power and the Word: Language, Power and Change. London: Paladin,

Ferguson, Charles

A., and Shirley Brice Heath, eds. Language in the USA. Cambridge: [26] Kiparsky, Paul.

"The Role of Linguistics in a Theory of Poetry." Language

as a Human Problem. Ed. Morton Bloomfield and Einar Haugen. New York:

Norton, 1974. 233-46. Saussure, Ferdinand

de. Course in General Linguistics. Trans. Wade Baskin. New York: [27] .Talking Voices:

Repetition, Dialogue, and Imagery in Conversational Discourse. Watkins, Calvert.

"New Parameters in Historical Linguistics, Philology, and Culture |