|

Reserve Text: John B. Gabel, The Bible as Literature, 5th edition Chapter 19 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2006) Chapter 19 Partly in response

to this oversight, and partly following the impetus of women's suffrage

move-ments in the United States, a "Reviewing Committee" of

American women intellectuals led by the notable suffragist Elizabeth

Cady Stanton (1815-1902) decided to publish their own comments on the

Bible, intending to limit their attention to the small part of the Bible

that explicitly focuses on women. Their efforts produced a landmark

work, The Woman's Bible, which appeared in two volumes, in 1895 and

1899. Elizabeth Cady

Stanton and the Reviewing Committee knew well that no book in Western

literature had had more impact on women than the Bible. It had been

invoked for two millennia to justify women's place in society; movement

away from biblically defined roles had consistently met with opposition.

Cady Stanton and her associates, aware of the Bible's influence as foundational

literature, believed not only that |

||

|

[328]

_________________________________________ the Bible had been appropriated by men for their own interests, but also that it was itself the product of male authors who claimed a special relationship with God that they used to exploit their own power over women. Cady Stanton explains:

______________________________________________ *Elizabeth Cady Stanton. The Woman's Bible (New York: European Publishing, 1895), p. 12. [329] Part of the problem,

clearly, was the Bible's status as authoritative even (maybe even particularly)

in English translation. "Whatever the Bible may be made to do in

Hebrew or Greek," she noted, "in plain English it does not

exalt and dignify woman" (p. 12). Cady Stanton's

approach to the Bible was remarkably "modern" and sophisticated.

To her, the Bible was not the unquestionable, unerring word of God but

a human composition reflecting human concerns. The part that it had

played in the oppression of women was proof enough for her that human

hands and minds lay behind its composition. As a human creation, she

reasoned further, the Bible could be questioned, analyzed, and interpreted.

But noting that biblical interpretation had historically been exclusively

a male-dominated activity, Cady Stanton brought to bear on The Woman's

Bible a conviction expressed by fellow suffragist Mathilda Joslyn Gage

at the 1878 Annual Meeting of the National Woman's Suffrage Association:

namely, the basic right of every woman to interpret scripture. Thus

a remarkable characteristic of The Woman's Bible was that it removed

the Bible from the hands of specialists and handed it to the people

who had been most harmed in the history of its interpretation. Those

who worked on The Woman's Bible were not trained biblical scholars,

but they were nevertheless canny readers sensitive to metaphor, allegory,

and symbolism, and to the manner in which modern readers interpreted

these modes of literature as historical fact. Those of us who study

the Bible as literature--both men and women--in a sense owe a great

debt to the work of the Reviewing Committee for establishing both method

and mandate in biblical studies. The Woman's

Bible--probably because of its radical implications for politics

and theology--proved to be unpopular. Elizabeth Cady Stanton's appeal

to women scholars to investigate the Bible remained largely unheard

until 1964, with the publication of Margaret Brackenbury Crook's study,

Women and Religion. Crook begins her book:

_________________________________________ WOMEN AND THE

BIBLE: ISSUES AND PERSPECTIVES There have been,

in the century after Elizabeth Cady Stanton, many women who have carved

out a role for themselves as feminist interpreters of the Bible. The

word "feminist" here bears some examination. It is feminist

to privilege women's productions over those of men. It is also often

the goal of feminist biblical interpretation to seek to highlight and

reverse the part that the Bible has played in the long history of injustices

against women. Feminist scholars see the Bible as an It is important

to remember that "feminist" is not a monolithic category any

more than "Christian" or "Jewish" is. "Feminist"

scholars evince a variety of interests and a variety of methods, and

often widely differ on what modern readers should do with the recognition

that the Bible is profoundly

male-oriented. On one end of the scale, there are "radical feminist"

interpreters who argue that the Bible is so thoroughly ideologically

loaded with male-dominated, patriarchal concerns that the only option

is to reject it entirely. In 1973, the radical American feminist Mary

Daly spearheaded a movement to reject the inherent patriarchal ideologies

saturating the Bible. Asked if the Bible might still be useful to women

if its patriarchal language and ideology were removed, Daly retorted,

"It might be interesting to speculate upon the probable length

of a 'depatriarchalized Bible.' Perhaps there would be enough salvageable

material to comprise an interesting pamphlet." * Daly calls not

just for a rejection of the Bible, but in her work subverts the entire

English language, the very structure of which she finds deeply informed

by patriarchalism. She calls for women to find a metalanguage to think

and talk about God beyond that which is contained and expressed in the

Bible, beyond "God the Father." Few feminist interpreters

of the Bible, however, have presented a body of work as remarkably controversial

as Mary Daly's. On the other end of the scale, there are many "moderate"

feminist literary critics who study the particular language and characterization

of women in the Bible without finding the need to reject the Bible entirely.

Many of these scholars simply turn the reader's eye to the variety of

ways in which women (or feminine imagery) figure in the Bible. Others

look more broadly at issues of gender in the Bible-that is, the ways

in which gender is operative in the construction of a character or narrative

action. These scholars investigate power relations between the sexes

as well as the social constructions of sexuality, including the ideas

of "femininity" and "masculinity." Feminist literary

critics have developed specific methods and techniques that they employ

when reading the Bible. They aim to "place women back in the center

of the frame," that is, to read the Bible as closely as possible,

paying particular attention to women, to gendered language, and to gendered

imagery. We can now consider three interrelated "points of departure"

for examining the interplay between women and the Bible: 1. The reader must engage in a careful and active reading of the text. By this, feminist literary critics mean that the reader not only should fully engage the text intellectually but must also recognize and acknowledge ______________________________________ Most feminist reading

strategies actively query biblical text and narratives. This process

poses text-specific questions to draw out issues involved in authoring

narratives. Thus a reader might focus on a particular biblical narrative

and pose a series of questions: What character(s) speaks? What character(s)

remains silent? What character(s) acts? What does the author state explicitly

and what only implicitly? What are the ideological concerns or agendas

behind the text, and how does the author use language to convey (or

mask) these concerns? The first step in an active, engaged reading,

therefore, is to develop a dialogical or dialectical relationship with

biblical text. What makes this undertaking "feminist" is that

it seeks to place particular focus on the constructions of women and

gender within this text. 2. Central to most

feminist readings is the assumption that the Bible is a profoundly androcentric

cultural artifact in which women either do not speak directly or are

made to speak against their own interests. It is not enough to ask questions

of a text; the questioner must keep in mind that the answers can reveal

only patriarchal concerns, not the authentic voices of women. Recognizing

that ancient texts written by men speak on behalf of women and thereby

craft modern perceptions of gender is part of a feminist hermeneutical

process often called "unmasking the dominant culture." The

feminist theologian Elizabeth Schussler Fiorenza has been the most active

advocate of a reading strategy she calls the "hermeneutics of suspicion."

Reading with "suspicion" means, in this case, that we understand

that biblical texts are androcentric, the selective articulations of

men that act to craft and support patriarchal social structures and

ideals. A step beyond the recognition of the Bible's androcentrism is

the reader's refusal to accept the text as either objectively "authoritative"

or "true." Instead, the feminist reader maintains a position

of critical "suspicion" and distance from the implicit motives

of biblical authors. 3. The Bible does

not help us to understand much about the lives of ancient women. It

helps us to understand, primarily, how ancient men thought about women.

No amount of careful reading of the Bible will reconstruct the lives

of real ancient women, because this was not the concern of the biblical

authors. Rarely, if ever, do women in the Bible speak for themselves.

Female characters do speak, of course, but these characters were created

by men, not by women. Even if we choose to focus pri- [333] marily or exclusively

on women in the Bible--and there are many books out there that do this--we

cannot truly learn about the lives of real women who lived during the

vast expanse of time in which the various writings of the Bible were

composed. We can learn only about the ways in which men felt compelled

to portray women. It might be helpful

here to start with an example of a feminist "reading" of one

particular character in the Bible, using the strategies we have outlined

above. We might start with Mary, the mother of Jesus, in two of the

places where she appears: the gospel of Matthew's infancy narrative

(Matt. 1:1-2:23) and the gospel of John's account of the miracle of

Cana (John 2). You may have noticed in your own readings of the Bible

that its female characters are often "flat," that is, lacking

dimension or characterological depth. Thus a careful reader will notice

that Mary has no dialogue in Matthew's narrative of her miraculous pregnancy

(Matt. 1:18-2:23); she is simply acted upon and spoken about by male

characters, in this case the angel of the Lord and Joseph. We have no

idea from this gospel how she feels about her predicament, but consider

what a young woman might have felt in that situation: she is pregnant,

though she has no idea how or why. Given the unusual circumstances of

her conception, she might not even know herself that she was pregnant

until her body began to show the unmistakable signs. A reader will notice,

too, that not only are Mary's emotional responses to her pregnancy never

detailed, she is never given an explanation for what is happening to

her body. In this gospel, the angel of the Lord explains Mary's pregnancy

not to Mary but to Joseph, in his dream at 1:20. In a classic case of

literary irony, the reader shares her knowledge of why Mary is pregnant

with the omniscient (male) narrator and other male characters, though

Mary herself remains in the dark. In Matthew's infancy narrative, Jesus' mother Mary is more of an object than a character; she functions primarily as a human receptacle for the unborn Jesus. In the gospel of John, Mary functions as a sym- _________________________________

Female characters,

then, although they cannot teach us about ancient women, can teach us

a great deal about ancient attitudes toward the sexes, about the manner

in which biblical writers envisioned and understood the proper roles

for men and women, and about the writer's ultimate theological goals. Now that we have

some basic critical tools for examining the broad [336] As is frequently

pointed out in this book, the Bible is a composite document, comprising

various genres of literature such as genealogies and king lists, laws

and legal prohibitions, tribal and founding narratives, proverbs, poetry

and psalms, parables and teachings. Each genre is shaped by slightly

different societal rules, and accordingly, women are represented differently

in different types of literature. It will be appropriate to take a brief

look at some of the ways in which women appear in these different genres. WOMEN WITHIN

THE BIBLICAL GENRES To begin, we can

consider genealogies and other lists. These are records of ancient societies,

important documents detailing the origins and memberships of tribes

and clans. Genealogies are not the most interesting reading, and often

students are tempted to simply gloss over them. But genealogies can

be very revealing! A careful reader might notice, for instance, that

women are almost entirely absent from the genealogical lists of Genesis

4:17-26,5:1-32, and 10:132. Since these lists are largely patrilinear-that

is, they trace ancestors through the male line of family succession-it

is not particularly surprising that women are absent. But there a few

interesting exceptions in which women do appear in these lists. In Genesis

4:19, for instance, a descendent of Cain named Lamech takes two women,

Adah and Zillah, as his wives. These two women bear sons who play prominent

roles as bringers of culture (4:20-22). By their presence in this list

of esteemed ancestors, these women appear to be recognized in a maledominated

literary form for their contribution to the development of culture. In New Testament

genealogies, there is an interesting difference between Luke's list

of Jesus' progenitors, which excludes any mention of women by name (Luke

3:23-38), and Matthew's list (Matt. 1:1-16). A close reading of Matthew's

genealogy of Jesus reveals, in the course of forty-one generations of

male ancestors of Jesus, the names of four women: Tamar (1:3), Rahab

(1:5), Ruth (1:5), and the wife of Uriah (i.e., Bathsheba) (1:6). Why

these four women? They are hardly the most prominent matriarchs in the

Old Testament. It may be that these women were selected because each

bore a child under the cloud of scandal: the widow Ruth bears the child

of her husband's kinsman Boaz so that she may continue her husband's

family line (Ruth 2-3); the wife of Uriah is drawn

into an adulterous relationship with King David by whom she conceives

Solomon (2 Sam. I I: 1-26); Rahab is a prostitute Gosh. 2); and the

widow Tamar disguises herself as a prostitute and seduces her father-in-law

to secure her familial rights and the succession of her husband's family

line (Gen. 38). Perhaps, then, the author of Matthew's genealogy of

Christ deliberately included four women whose personal circumstances

with respect to the status quo mirrored, by loose analogy, Mary's plight

as the mother of a child conceived outside of wedlock. They were all

women whose sexual morality was questioned or questionable but who also

bore their liminal sexual identity willingly to further the line of

Israelite succession that would lead, ultimately, to the birth of] esus

the Messiah. Their identity as mothers, furthermore, is paramount; in

every case, Matthew describes the women as "mother [of] ...,"

breaking the repetitive rhythm of the male genealogical for mula that

repeats the word "father" like a refrain. For the author of

the gospel of Matthew, these four women's questionable morality is vindicated

or justified by their theological importance as mothers and the way

in which they pre-figured Mary as ironic heroines. In fact, they act

to prefigure, prepare, or point the way to the culmination of the genealogical

line: not]oseph (whom the author of this material pointedly refuses

to call]esus' father), but Mary, "of her was born]esus." In

this way, we can see that a supposedly ideologically "neutral"

document like a name list or genealogy actually contains the potential

to make a deliberate point on a very subtle level. Laws and Legal Rulings Laws and legal rulings are a second type of documentary material constituting large sections of the Old Testament. Women figure in these patriarchal codes as property or commodities, and as legally disadvantaged compared to men. Exodus 20:17, for instance, lists women as part of a man's legal property, along with a man's house, slaves, and livestock. Most laws in the Hebrew Bible are constructed in such a way that the ontological inferiority of women appears to have been taken for granted. Even the relative economic values of men and women differ; between the ages of twenty and sixty, when human beings are at their most productive, the book of Leviticus (Lev. 27:3-7) assesses the value of men at fifty shekels but women at only thirty shekels! Purity laws portray women consistently as essentially defiled and defiling, particularly because of menstruation and childbirth (Lev. 12, 15). These purity laws are not to be confused with notions of hygiene or uncleanliness; instead, they aimed to keep the male priesthood of the Temple cult ritually pure enough to stand in Yahweh's presence. This cultic purity (Hebrew qedushah or tohorah) |

||

|

[338] could easily be

"canceled out" if priests came into contact with most bodily

fluids including their own; thus semen was as polluting as menstrual

blood. A man incurred pollution (Hebrew tum'ah) during sexual intercourse

because of his own seminal emission, not because he came into contact

with a woman. Women's purity, on the other hand, did not need to be

as carefully regulated as men's or as priests' purity, simply because

in this culture, women (unlike men) could never stand in the presence

of Yahweh. The ancient Israelite

conviction that women could not stand in the presence of Yahweh is brought

home poignantly in arguably the most significant episode outlining the

nature and status of the Law in the Old Testament: when Moses receives

the Ten Commandments from Yahweh (Exod. 19-20). Accordingly, one of

the most disturbing passages for feminist biblical interpreters occurs

in this same narrative, when Moses warns his people at Exodus 19:15,

"Be ready for the day after tomorrow; do not touch a woman."

At the moment when the people of Israel stand ready to receive the covenant,

Moses turns to them but recognizes and addresses only the men. The issue

here was one of ritual purity, since a seminal emission made both sexual

partners temporarily impure. But Moses does not say, "Men and women,

stay away from one another." What disturbs feminist readers is

not just the author's tacit assumption that women are defiling--it is

that as he turns to the "people," women are for all intents

and purposes invisible; in this passage, Moses' implied audience, the

"people of Israel," consists only of men. Is there any way

around the conclusion that women seem to have been excluded from Mosaic

Law and treated as pariahs in the Deuteronomic and Levitical codes?

Some readers of the Bible point out that compared to other ancient law

codes, women actually fare better in the Bible. In other roughly contemporaneous

texts, like the Hammurabic Code, women are valued even less highly.

A careful reader might notice, too, that many Levitical passages carefully

balance legislation for men and women without unduly favoring men; consider,

for instance, Leviticus 15:13-15 with Leviticus 15:28-30, where almost

identical wording is used to describe how both men and women can cleanse

themselves from ritual impurity. In any case, it is helpful to place

ancient laws in their proper social context: they were constructed by

members of an elite male priesthood preoccupied with purity issues,

often far removed from the social realities of women. Although many people assume that the Old Testament emphasizes laws while the New Testament emphasizes revelation and the life of Jesus, there are actually many passages and sections of the New Tes- |

||

|

[339] tament that, one

way or the other, present a new set of laws aimed at Christians, often

to replace or "update" the laws of the Hebrew Bible. To give

only one example, an important set of laws in the Pastoral Letters (I

Timothy, 2 Timothy, and Titus) known as "household codes"

have particular bearing on the status of women. Examples of these codes

are found at I Timothy 4:12; 6:1 I, and 2 Timothy 2:22 and 3:10. Their

purpose is to delineate the appropriate social and domestic roles for

members of an extended household and a fledgling church. Although these

codes do not have the rhetorical force of divinely ordained law, they

have nevertheless been hugely influential in the construction of women's

ideal role in Western society. Consider the words ascribed to Paul in

I Timothy 2:11-14: "During instruction, a woman should be quiet

and respectful. I give no permission for a woman to teach or to have

authority over a man." The author then invokes his particular reading

of Genesis 2 to justify his understanding of the proper social order:

"A woman ought to be quiet, because Adam was formed first and Eve

afterwards, and it was not Adam who was led astray but the woman who

was led astray and fell into sin." His reading is not a summary

of Genesis 2 but an interpretation of it. Modern readers might argue,

for instance, that both Adam and Eve were led astray, and that the Genesis

narrative itself never includes the term (or the notion of) "sin."

Nevertheless, I Timothy 2:11-14 is a remarkable piece of early Christian

legislation that employs Hebrew scripture for its justification and

that through its presence in the Christian canon has been used for two

millennia in the subordination of women. Since laws are

primarily prescriptive--that is, they represent not social reality but

social ideals of behavior--many women interpreters of the Bible advocate

reading "against the grain," a subversive reading technique

designed to highlight the manner in which laws are constructed according

to male concerns for maintaining domination over women. To return to

the example of I Timothy 2:11-14, the author of this passage adds a

final word on women's proper place: "Nevertheless she will be saved

by childbearing, provided she lives a sensible life and is constant

in faith and love and holiness" (I Tim. 2:15). Rather than take

these words at face value as biblically mandated law, we might read

"against the grain" and infer from them that at the end of

the first century C.E. when I Timothy was composed, many Christian women

were evidently electing to remain childless and perhaps even to play

more active roles as teachers or ministers. By contrast, the fledgling

Church needed to establish and control its new communities. Women's

decisions to abstain from having children, then, probably threatened

to destabilize many early Christian movements. Thus ecclesiastical "laws" [340] or sanctions were

created to serve the needs of this community. Household codes are therefore

not descriptive of social reality but rather prescriptive, strongly

advocating a set of behaviors to curtail women's activities. Reading

"against the grain," we can recognize that the ruling that

states that women will be "saved" by staying at home and giving

birth was immediate, contextual, and in a sense, in reaction to what

women were actually doing. Tribal Narratives and Founding Stories Genesis, Numbers,

and Exodus place at their center stories of the patriarchs. The patriarchs

lead by virtue of their position as mediators between God and the people.

Although the patriarchs' behavior may not always fit within modern parameters

of morality or heroism, there is no question that various biblical authors

meant the patriarchs to stand as powerful exemplars for a man's proper

relationship to his God. Part of that proper relationship included the

unstated and unquestioned assumption that women were primarily commodities

and essential only for reproduction. By "commodities," we

mean that women had primarily economic value, not just for their ability

to bear children to share the burden of labor and protection of the

tribe, but also for the dowries that they brought to a marriage. Women

thus served important, albeit passive, roles in the transmission of

wealth through marriage and kinship ties. In the ancient

world, women were also war trophies. The rape of women during invasion

served multiple functions: to channel male aggression, to defile another

man's property, but also to mark women (and by extension, their peoples)

as now part of the conquering group. There is an old story about a conversation

between a tribesman and a modern ethnographer: the tribesman points

out a settlement in a neighboring village and explains to the ethnographer,

"They are our enemies; we marry them." Thus in Judges 2 I,

for example, the Benjaminites use wife stealing and rape as a way to

forge new kinship identities. The secondary status of women in tribal

narratives also accounts for stories such as the rape of Dinah with

its tragic consequences (Gen. 34)' Although her rape at the hands of

Shechem renders Dinah "unclean" (Gen. 34: 5, 27) and what

not long ago people used to call euphemistically "used goods,"

this story is not so much about the victimization of women as it is

a tale of male rage and vengeance. Dinah's brothers respond to the violation

of their sister by raping a number of women from Shechem's tribe, an

act that is seen in Genesis as appropriate and morally justifiable. One more "founding story" bears some attention: the creation of the Abrahamic Covenant (Gen. 12:2; 13:15-18; 15:1-21). In this story, [341] Yahweh lays out

a mutually binding contract with his servant Abraham. Yahweh promises

to give Abraham land and offspring ''as numerous as the stars"

if Abraham consecrates his (male) children to Yahweh. The mark of this

covenant is male circumcision. Remarkably, women are absent from the

Abrahamic Covenant, leading some Jewish feminists to ponder whether

Jewish women are really Jewish at all, since they are not technically

bound by the covenant, the tangible symbol of which is a marking or

mutilation of the male body. In this sense, the Abrahamic Covenant stands

as the foundational story of patriarchy as father-right, a story that

gives women no part to play in the foundation of the "people of

Israel" other than as breeders, and a story that marks men's privileged

relationship with their deity into the flesh of the male generative

organ. Parables and Teachings The parables of the gospels are a unique literary form. As didactic literature, they depend on illustrative vignettes that deliver complex and abstract information to the reader or listener in terms that she will be likely to understand. Thus the parables employ analogy to describe the "Kingdom of God" or the "Kingdom of Heaven"; they indicate what things are like the Kingdom in a provocative way that encourages reflection and contemplation. From the perspective of women and the Bible, the parables stand apart because they appear to have been designed for two separate audiences-one male, the other female. Thus parables are often paired, reflecting both male and female experiences of the world. For example, in both Matthew and Luke, the Kingdom of God is like a (male) farmer sowing the tiny mustard seed that grows into the large mustard plant, but it is also like a woman adding a tiny bit of yeast to dough that is able to make three measures of flour rise (Matt. 13:31-33; Luke 13:18-21). Through the use of simile and the linking of these analogies to what was traditionally "men's work" and "women's work," the author of these passages delivers the same message to both men and women. Two parables in the gospel of Luke-those of the lost sheep (Luke 15:3-6) and the lost coin (Luke 15:7-9)-function similarly: to deliver a message about God's desire to seek out sinners rather than the righteous of Israel. In all these paired analogies, we might notice, women's work is portrayed as of equal merit to men's work; it stands for the same thing. Furthermore, women in these parables are neither inferior to nor dependent on men. This attention to women as an audience is remarkable for its time and may give us hints as to the truly revolutionary nature and appeal of the early Jesus movement, particularly to women, Some concluding

observations are in order here. First, we must keep in mind that each

type of literature expresses its own particular concerns and agendas.

Metaphors of the feminine in poetry do not tell us about the social

lives of real women in the ancient Near East. Ritual regulations established

by and for a male priesthood limiting women's access to the holy do

not necessarily mean that women as a whole were limited in their social

functions or looked down upon as defiling. The absence of women from

tribal lists or genealogies does not mean that women were not active

participants in society as mothers or as transmitters of culture. At

the same time, this is not to say that, generally speaking, women in

the ancient Near East enjoyed greater emancipation or freedom than that

which is revealed in the Bible. The ancient Near East was a male-oriented,

male-dominated culture in which women's activities were almost always

severely curtailed. Second, it is important to remember that the different

types of literature in the canon emerged over more than a millennium,

from a broad range of ancient societies. The best we can do as modern

interpreters of the Bible is to recognize the multiplicity of voices

and sources contained therein, and to locate each discussion or portrait

of women within its particular historical and social context. Is God in the Bible

masculine or feminine? For many, the answer is obvious: God is male.

Yet feminISt biblical interpreters in the last two decades have encouraged

readers to be more thought On the other hand,

it is difficult to argue that Yahweh is not a he, since often in the

Bible Yahweh shows many of the male qualities associated with other

Near Eastern deities. He is a king, a mighty warrior, and an arbiter

of justice. He is also the leader of a tribal confederation that he

delivers from bondage and oppression. These roles--deliverer, ruler,

warrior, and judge--are traditionally male occupations, although there is of course

nothing essentially "masculine" about them. In fact, in the

everyday religious lives of ancient Israelites, Yahweh the warrior-leader

was effectively "paired" with the goddess Asherah, who was

worshipped by Israelites and the later Judahites. Yahwists outlawed

her cult in a bloody struggle recounted in 2 Kings (see particularly

2 Kings 22ff.). The triumph of a male warrior-god over a goddess (who

could also, in the ancient world, be associated with war and warlike

qualities) served to highlight the language of female suppression and

domination--not because Asherah was necessarily "feminine"

as a goddess, but simply because Yahweh, at least in the minds of the

Yahwists, was the better, stronger warrior whose cult more successfully

advocated the qse But there are also

a number of places in the Bible where God is described with feminine,

maternal metaphors, such as Hosea 11:3-4 or Isaiah 42:14: "groaning

like a woman in labour, panting and gasping for air." God's love

for humankind, therefore, can be articulated as a sort of "womb-love"-as

penetrating, fundamental, painful, miraculous, and beautiful as the

love of each mother for her child as she brings it into the world. In

fact, the Hebrew root word from which words for "compassion"

and "mercy" derive come from the word rechem, which means

"womb." The few instances

when God is given feminine attributes or imagery do little, however,

to lessen the overall impression that God is associated with qualities

traditionally gendered male, such as dominance, aggression, and bellicosity.

But these qualities are not themselves in herently "male";

they are male because our society (and many of the societies of the

ancient Near East) likewise essentialized them as male or masculine.

Accordingly, some feminists have objected to seeing biblical language

of God's birthing, for example, as inherently "feminine." Giving birth is

something women do. The act itself is not "feminine." To see

all Yahweh's acts of nurturing and parenting as "feminine"

and all acts of discipline and aggression as "masculine" speaks

not to the transcendent reality of those qualities but to our desire

to "fix" or assign these qualities to biological sex. These

decisions, and perspectives, about what is inherently "masculine"

and what inherently "feminine" are ultimately culturally determined. How these essentialized

notions of gender come into place in the character of God in the Bible

is actually fairly complex. Consider the example of Genesis 1-2, when

God creates the world in six days. Some feminist scholars see in Genesis

1-2:4a the founding myth of primordial patriarchy, in which God, the

masculine Sky Father artifex (one who creates by making or crafting

something) replaces the feminine [344] However, the Genesis

creation myth does appear to work with the category of gender in interesting

ways. To begin with, it seems to mirror other Near Eastern combat myths

such as the Enuma Elish, the Babylonian narrative in which creation

takes place through the vanquishing of a monster. In the Enuma Elish,

Marduk slays the great sea monster Tiamat (who appears once to have

been a deity in her own right) and divides her body to create the seas

and the sky. In the Enuma Elish, therefore, domination of the cosmos

occurs through the ritualized slaughter and subsequent dismemberment

of the divine female. And while Genesis picks up on this story-there

are traces of the Babylonian word for Tiamat in the Hebrew word for

"the deep," tehom, when God divides the firmament and establishes

the sky above and the deep below-the theme of the slaughter and dismemberment

of a divine sea goddess is present only vestigially, in the feminine

gender of nouns such as tehom. In this way, the creation myth of Genesis

is actually less misogynist and patriarchal than earlier Near Eastern

myths of creation. Genesis 1 also

contains traces of another divine female "character." In Genesis

1:2, "God's spirit" hovers across the water. In the Hebrew

language, the word for "spirit," ruach, is feminine. Some

Jewish readers of Genesis 1:2 during the hellenistic period interpreted

the roach (which can also be translated as "breath" or "wind")

as God's feminine partner and counterpart, a divine feminine creatrix

working in concert with God. This partnership is expressed most eloquently in Proverbs 8:23-31:

This feminine partner

of God was identified as Wisdom, to the point that in some hellenistic

circles, Wisdom was elevated to a sort of god dess in her own

right. Wisdom even shows up in some early Christian interpretations

of the Bible as the divine female Sophia, who is responsible both for

the creation of the world and for the implantation of the divine breath

or soul into all human beings. If the elevation

of God's breath to the wisdom goddess Sophia provides a remarkable example

of how language of the feminine divine shaped the reading of the Bible

over two and a half millennia, there are also indications that such

language was actively suppressed, even masculinized, to serve the aims

of patriarchy. Certain Christian writers replaced the feminine creative

agency of Wisdom with the dynamic, preexistent male Logos. In the prologue

of the gospel of John, for example, it is the (male) preexistent Christ

who was with God and who assists God at creation: "In the beginning

was the Word: the Word was with God and the Word was God" (John

1:1). Paul, too, notes that Wisdom and Christ are identical: "We

preaching a crucified Christ. ..who is. ..the wisdom of God" (I

Cor. 1:23-24). The transformation of the female Wisdom into the male

Christ supported Jesus' status in Christianity as a "son of God"

created alone in the "image of God." This emphasis on Christ's

maleness, in turn, reflected and justified a system of patriarchal rule.

In this system, a woman could know God only through a man, since in

the established, descending hierarchy of divine reflection, a man stands

closer to God through shared maleness than does a woman. That only men

reflected the "image of God" became in some New Testament

writings a cosmic principle; thus Paul notes in his first epistle to

the Corinthians, "But I should like you to understand that the

head of every man is Christ, the head of woman is man, and the head

of Christ is God. ...But for a man it is not right to have his head

covered, since he is the image of God and reflects God's glory; but

woman is the reflection of man's glory (I Cor. I I: 3, 7). Before concluding

this section on feminine imagery in the Bible and the ideological ends

that this imagery has served, it is important to discuss a few instances

in which the Bible's feminine imagery takes particularly ugly, troubling

forms. In prophetic literature, Israel is seen as the feminine, earthly

counterpart to God. While some biblical authors liken Israel to God's

"bride" (Jer. 2: 2 -3; Hos. 2: I 5), more troubling to feminist

readers is the common identification of Israel as an adulteress or even

a "whore." In Hosea 2: 1-3, for instance, Israel's capital

Samaria is likened to a sexually depraved wife stripped naked, imprisoned

in her house by her husband, and prevented forcibly from carrying on

her adulterous liaisons. God's "legitimate" role, according

to Hosea, is one of domestic abuser, who physically abuses his wife

to punish her for what he jealously perceives as her sexual infidelities. The characterization of Israel as "whore" and God as the angry, [346]

Commentators have

wryly noted the absence of this particular passage from Sunday school

curricula; but the language of violence Jeremiah employs here is part

of a widespread, enduring cultural system in which women's sexual identity

is invoked to justify violence against them. Israel's shortcomings in

meeting the calls of the divine are thus developed in gendered metaphors

that invoke the most negative terms possible for human women. But why? This question sits

at the center of womanist biblical interpreter and theologian Renita

Weems's book, Battered Love: Marriage, Sex and Violence in the Hebrew

Prophets (1995). Weems argues that the language of the prophets

is deeply and troublingly violent. Although this language is often "explained

away" as "merely metaphor," she wonders aloud in her

introduction (entitled "A Metaphor's Fatal Attraction") "what

in the image of a naked, mangled female body grips the religious imagination?"

Weems's aim, in unmasking metaphors of domination, is to simultaneously

unmask the way in which language functions powerfully to authorize and

legitimate male violence against women. If we understand

that the Bible is an anthology of works of literature, we can begin

to see how language works powerfully to create authority. God's giving

birth "like a woman" or caring for the people of Israel "like

a mother" does not make God a woman. God's "raising the [347] skirts" of

Jerusalem and exposing "her" shame in anger does not make

God a male rapist. Metaphor and simile function in the Bible to express

analogy, not identity. But if we forget that God is sometimes "like"

a male and begin to think that, in its place, God "is" a male,

we are misunderstanding language while at the same time allowing ourselves

to be deeply influenced by it. Many feminist scholars see this act of

for getting, of reading metaphor literally, as an act of idolatry. It

is "idolatry" because what is being worshipped is a verbal

"image" of God, not God's transcendent reality, which is by

definition beyond humanly created language and socially constructed

categories of gender. More often than not, we are left after reading

much of the Bible with an image of God not as nurturing mother but as

an angry and vengeful father and husband. The ideology of "father-right"

expressed through biblical, even poetic language justifies not only

the subordination of women but even the most egregious acts of violence

against them. Only the recognition that language is humanly constructed

can move us away from interpretations of ideological absolutism with

its sometimes tragic human consequences. A brief survey of the female character in the Bible should start with the Bible's first narrative, the creation of Adam and Eve and the so-called Fall of Man in Genesis 2-3. No other biblical narrative has played such a profound role in defining "normative" roles for women, or for creating the convictions that women are inherently sexual, deceitful, impulsive, and rebellious. Remarkably, these viewscome not from Genesis 2-3 itself, but from the history of its interpretation, from early exercises in biblical exegesis to John Milton's Paradise Lost. Genesis 2-3 is a narrative about the transition from an idyllic, well-provisioned Eden closely monitored by God to an imperfect "real world" with its cycles of time and change, birth and death, and a human race that must work hard to exist. As a narrative, it is also remarkable for its female protagonist. It is Eve (identified only in Genesis 2-3 as "the woman," just as Adam is merely "the man") who drives the narrative action, not Adam, who plays an almost comically passive role. The man takes the fruit from the woman like a baby (3:6) and is quick to blame the woman for offering it to him in the first place (3: I 2). On the other hand, the woman makes a reasoned (and reason able) decision to take and eat the fruit. Her action initiates a moment from which culture evolves in its manifold forms: in established gender roles, the development of agriculture, the human domination of animals, the wearing of clothing. The woman emerges in Genesis 3 as no |

||

|

less than a culture

bringer, like the Greek hero Prometheus who steals fire from the gods

and brings it to humankind. The woman's role as culture bringer is perhaps

reflected in the Hebrew name that Adam bestows on her, "Eve,"

which contains a wordplay that lauds her as the "mother of all

those who live" (3: 20). But Eve's significant

role in initiating human civilization is obscured by more traditional

patriarchal evaluations of the first woman as inherently deceitful and

sexual-two character qualities that seem to conveya deep distrust of

women. Nor is Eve the only female character in the Bible through whom

the theme of the deceitful woman is expressed. Indeed, many of the Bible's

heroines achieve their goals through deceiving their husbands, fathers,

or enemies. Trickery and deception mark the narratives and characterization

of, for instance, Rebekah, Rachel, and Tamar, and the midwives, mother,

and sister of Moses (Exod. 1-2). In Genesis 27, Rebekah drives the action

of the narrative as the primary actor. She tricks the dying Isaac into

giving his blessing to Jacob rather than to Esau, his favorite son,

thus successfully manipulating the continuation of the Abrahamic line

and promise through Jacob. Rachel tricks her father-in-law Laban by

stealing from him the teraphim (household gods); when he comes in search

of them, Rachel sits on them and tells Laban she cannot get up, because

she is in the middle of her menstrual period (Gen. 31:19, 30-35). Tamar

disguises herself as a prostitute and tricks her father-in-law, Judah,

into having sex with her to secure her rights under the laws of Levirate

marriage, ensuring that her offspring will continue her husband's familial

line (Gen. 38). But readers should

not misinterpret trickery as a negative trait of biblical women. Male

characters in the Bible also act as tricksters. Consider Abram passing

off his wife, Sarai, as his sister in the folktale-like "wife-sister"

tales (Gen. 12:10-20; 20:1-18; 26:1-17), or Jacob tricking Esau out

of his birthright (Gen. 25:29-34). In fact, the trickster figures prominently

in the folklore and folktales of peoples traditionally lacking political

voice or power. An example of trickster tales familiar to American readers

might be the Brer Rabbit stories circulated among Mrican American slaves

in the plantation South. In these tales, the hero Brer Rabbit often

gains the upper hand through tricking the more powerful or sophisticated

Brer Fox or Brer Bear. Far from simple allegory or fable, trickster

tales betray a moral complexity: they express instances in which underdog

characters learn how to exploit and subvert authority, to negotiate

complex power relationships in society through superior cleverness and

determination. Given women's lack of power in the ancient Near East,

the adaptation of trick- ster motifs to

the female character reflects an authentic means for women to exert

power subversively and successfully in a patriarchal system. Rebekah,

by transferring her husband's final blessing from his favored son to

her own, exerts the only power a woman possesses in a man's world; her

actions are not without dangerous implications and self-sacrifice, and

she accepts the consequences of deception: "On me be the curse,

my son!" (Gen. 27:13). Rachel, for her part, employs a patriarchal

perception for her own ends; she uses the male-created law that a menstruating

woman is "unclean" and should not be touched to prevent a

man from touching her and discovering her hidden cache of household

gods. Tamar the widow plays with male sexual desire and the patriarchal

division of women into "virtuous" and "loose," moving

from one category to another and back again to achieve her goal of securing

the marriage and offspring necessary for her and her family's survival. The "deceitful woman" is a narrative theme more sophisticated than the themes of some other female characters who populate the Bible: the barren woman (Sarah, Rachel, Elizabeth; the unnamed mother of Samson in Judges 13), the unloved or abandoned woman (Leah, Hagar; the unnamed "adulteress" of John 7:52-8:11), the violated virgin (Dinah), and the dangerous hypersexual woman (Delilah, Salome, J ezebel, and the Whore of Babylon). These are not portraits of real women, but the archetypal, stock characters of folktales. The motif of the barren woman reflects the culture of the ancient Near East where married women unable to conceive suffered humthation, failing at the only social role afforded to them; but it also serves to highlight the theme that with Yahweh's help, all things are possible. Since the miraculous or extraordinary circumstances of a hero's birth also form a common motif in mythology, the theme of birth from a previously barren woman is not so much about an authorial concern with women's sorrow and humthation as it is a stock element provided to support a man's heroic, privileged status. The dangerous sexual temptress, by contrast, amplifies men's fears of losing control to women in the complex power negotiations between the sexes through the only power men cannot fully control: sexual attraction. The sexual siren bent on the wanton destruction of a man-like Herodias' daughter traditionally known as Salome who demands John the Baptist's head as "payment" for her dance (Matt. 14:1-12; Luke 9:7-9; Mark 6:14-28)-represents a distillation of these fears. Thus all these biblical figures, however good or bad, however well articulated or merely sketched out as characters, are not historical portraits of real women. They come from a wellspring of motifs or archetypes common to world mythology--a point explored by Not all female

characters in the Bible are merely caricatures or stock character "types."

Some are finely and sensitively drawn, and we learn a great deal about

their motivations, their desires, and their sense of self. Three of

the matriarchs of Genesis-Rachel, Sarah, and Hagarcall upon Yahweh to

explain or ameliorate their plight, and all three receive answers and

divine favor. Sarah, on overhearing that she will conceive in her old

age, bursts into incredulous, even scornful laughter (Gen. r8:r2). When

Yahweh questions Abram sharply on his wife's lack of faith (r8:r3),

Sarah quickly backtracks: "I did not laugh" (Gen. r8:r5).

Here, Yahweh gets the last word not once but twice: "Oh yes, you

did laugh," he responds to her. And of course, that spring, Sarah

bears Isaac, whose name means "he laughs'" (see Sarah's pun

at Gen. 2 r :6). Rebekah, suffering from the crush of two battling fetuses

in her womb, asks Yahweh in desperation, "If this is the way of

it, why go on living?" (Gen. 25:2r-23). Yahweh answers her with

a prophetic statement underscoring her importance as a vessel bearing

two nations (Gen. 25: 2 3). Finally, the Egyptian slave woman Hagar,

cast out to die by her mistress Sarah in the wilderness of Beersheba,

places her child Ishmael under a bush and retreats far off so that she

does not have to endure the sight of his death (Genesis 21:16; see the

alternative version of the story at Genesis 16:1-15). Hearing the infant

Ishmael howling in the wilderness, Yahweh speaks to Hagar directly:

"What is wrong, Hagar? Do not be afraid, for God has heard the

boy's cry in his plight" (Gen. 21:17). These incidents make it

clear that female characters, too, can converse with God, and the nature

of that conversation is not fundamentally different from that between

male characters and Yahweh. In fact, Yahweh makes a separate covenantal

promise to Hagar closely related to the Abrahamic Covenant: "Go

and pick the boy up and hold him safe, for I shall make him into a great

nation" (Gen. 21:18; compare 17:7-8, 16). Hagar, as a consequence,

becomes the only woman in the Bible to name God: "Hagar gave a

name to Yahweh who had spoken to her, 'You are EI Roi,' by which she

meant, 'Did I not go on seeing here, after him who sees me?'" (Gen.

16:13). Female characters can also become central actors in the Bible as martial heroines, playing out one of the dominant themes of the Old Testament: the necessary and divinely sanctioned domination of the people of Canaan through acts of violence and aggression. The heroine of the book of Judges, Deborah, is described as both prophetess and judge, and explicitly depicted as a leader of men (Judges 4:8-9). Deborah's prophecy that Yahweh will give over the Canaanite leader Sis- [351] era "into

the hands of a woman" is fulfilled whenJael, the wife of Heber,

lures Sisera into her tent and drives a tent peg into his temple with

a hammer when he is sleeping (Judges 4:21). For this deed, Jael is commemorated

in one of the oldest parts of the Bible, the Song of Deborah: "Most

blessed of women be Jael / (the wife of Heber the Kenite); of tent-dwelling

women, / may she be most blessed" (Judges 5:24). The story of Deborah

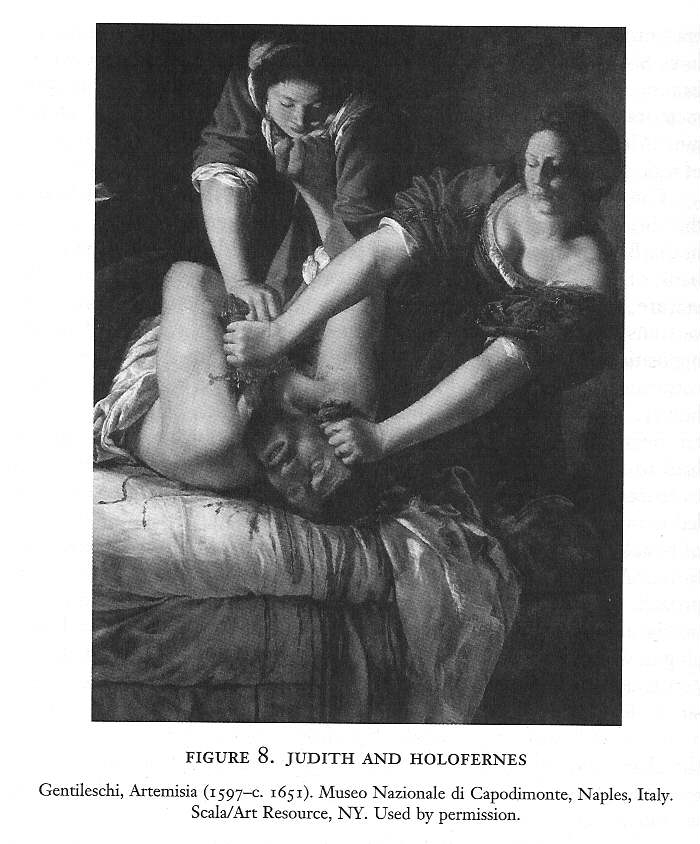

is echoed in the tale of Judith from the book that bears her name. (She

is one of four women for whom a book in the Bible is named; the others

are Esther, Ruth, and Susanna.) The book of Judith is an extraordinarily

well-crafted work of ancient literature, replete with chiastic structures,

irony, suspense, narrative inversions, double meanings, and tensions

based on a series of binary oppositions: women versus men, Jews versus

non-Jews, courage versus cowardice. Judith is a widow, steadfast in

her piety, renowned for her beauty. The author takes pains to establish

Judith's blameless character; hers is the longest genealogy given for

any biblical woman, tracing back to her ancestor Jacob (Jth. 8:1). But

to what extent is Judith meant to represent a real woman? Her name,

which means only "Jewess," has led many observers to suggest

that she is a personification of the land of Israel-an interpretation

favored, incidentally, by the Protestant reformer Martin Luther. Although

her behavior as a widow is beyond reproach, she too bears elements of

the trickster. Her words are full of outright and manipulative lies

(10:12-13; 11:11-15); her part of the dialogue with Holofernes in his

tent-a masterful scene of narrative suspense and tension-is full of

double entendres that she and the reader share, leaving Holofernes the

comical victim of literary irony (II: 5; 11:6; 12:18). And as the book

of Judith is full of tensions, so too is the character, Judith. Is she

a feminist heroine, a true woman warrior; or a bloodthirsty projection

of patriarchal fears, the embodiment of women's "lethal love"? A final category

of female character worthy of brief examination is the forgotten, mute,

or terrorized woman. In 1984, feminist biblical scholar Phyllis Trible

published her Texts of Terror: Literary-Feminist Readings of Biblical

Narratives, in which she highlighted and thus honored many of the

forgotten, nameless women who were violated within the patriarchal,

misogynist worldview of the Bible. Thus she discusses in detail the

rape of Tamar by Amnon (2 Sam. 13), the story of Dinah (Gen. 34), and

most poignantly, two horrifying stories from the book of Judges: the

unnamed concubine who is offered up to strangers in an act of "hospitality,"

gang raped and tortured, then dismembered by her master (Judg. 19:1-3°),

and the sacrificial killing of a daughter by her own father, Jephthah

(Judg. 11:39). Jephthah slaughters his vir-

________________________________ Where female characters are not given the opportunity in biblical narratives to speak for themselves, one technique feminist readers some times employ is called amplification. Amplification involves creative imagination and a modified version of a Jewish rabbinic practice called midrash ("commentary") to fill out the parts of a narrative where female characters are unable to speak. Amplification restores voice and agency to biblical women. A feminist amplification of the Sarah and Hagar story, for instance, might explore and expand upon the relationship that the two women might have had-a relationship of no particular interest to the biblical authors. Feminist midrashic readings have creatively illuminated not only Hagar's plight as an outsider, a slave, and an unmarried pregnant woman rejected by both the man who impregnated her and his angry wife, but also her status as the only woman to whom God appeared directly in the wilderness and the only woman in the Bible to "name" God. Feminist midrash also amplifies the thoughts and sorrow of Sarah, as she wakes in the morning to find that Abraham has gone at Yahweh's behest to sacrifice her only child, conceived in her old age after a lifetime of suffering the heartrending fate of being barren in a society that prized female fertility. With the techniques of amplification or feminist midrash, feminist interpreters move from critiquing and analyzing fiction to creating it. The resulting literature can have extraordinary beauty and power. Furthermore, the popularity of such recent works of feminist midrash such as Anita Diamant's The Red Tent (1997),* which amplifies the story of Dinah and the other women of the Bible, speaks to the need for modern authors to recast biblical women into fuller, more vibrant roles. GENDER AND THE

PROBLEM OF TRANSLATION No study of the

Bible as literature can be complete without a discussion of the problems

inherent in translating ancient languages into modern English. And no

study of "women and the Bible" can be complete without a discussion

of the issues concerning gender that emerge during the translation process.

The English language, like the biblical languages Greek and Hebrew,

is gendered. English grammar has three genders, masculine, feminine,

and neuter, although the neuter remains only in a limited form. As most

writers at the college or university level now recognize, the convention

of using gender-specific language such as "man" or "mankind,"

as well as the habitual and exclusive reliance on the male pronoun "he"

to modify all ambiguously gendered nouns such as "child,"

"person," or "reader," can act to obscure or negate

the participation of women in history. Con _____________________________________________________ |

||

|

[354] sider the English

use of "man" as a collective noun. "Man" stands

in opposition not to "woman" but to "animal" as

an ontological category. It incorporates,

not opposes, "woman," though only implicitly. Yet "woman"

really means "man's partner" or "the opposite of man,"

not the "opposite of animal." The noun "woman,"

unlike "man," never means "human being" generally

or as a whole. "Woman" is but a subset of "man." To combat the interpretive

problems inherent in gender-exclusive language, a group of translators

and linguists produced in 1990 a controversial new English translation

of the Bible, the New Revised Standard Version (NRSV). It is important

to emphasize that the translators of the NRSV did not aim to expunge

"sexist" or misogynist language from the Bible itself. They

agreed that the Bible is the product of a patriarchal culture; their

job was not to fundamentally alter its contents Although most modern

readers are sympathetic to the notion of a [355] gender-neutral

Bible, there are translation points that have raised considerable controversy.

This is really not surprising, for gender-neutral translations undermine

our own patriarchal conditioning in which the masculine is prioritized

and sanctified and the feminine is repressed or rejected. When the familiar,

comforting expressions of the Bible are replaced by the unfamiliar,

some people reject them as "untraditional" or even "unfaithful

to the Bible." But consider that the function of language is not

always to reassert the familiar; language can work subversively, too,

to shock readers out of complacency. Terms like "fishers of all

people," back in the first century, would have struck most readers

not as comfortingly familiar but as shockingly new. Indeed, many interpreters

see biblical literature as often transgressive and revolutionary, encouraging

its readers to see the world differently. In the production of modern

gender-neutral translations of the Bible, we are forced to see not only

a familiar text but even ourselves differently. From this experience,

we can begin to see the power of translation in furthering ideas of

gender: language is powerful, and it is implicitly ideological. Could any of the

biblical authors have been women? For some time, scholars have at least

entertained this possibility. An American scholar of the Hebrew Bible,

Richard Elliott Friedman, raises the issue in his book, Who Wrote

the Bible? (1987).* Friedman notes that while many of the writings

of the Old Testament clearly reflect the concerns of men-particularly

male priests-there are other writings that seem particularly sympathetic

to women. He gives the example of the portrayal of Tamar in Genesis

38. Not only do these passages focus attention on a female character,

but in them Tamar acts independently to come up with a plan to redress

the wrongs done to her, and she manages to elicit the apology of Judah,

who reiterates her rights. As we have already seen in this chapter,

equally sympathetic to women are some of the narratives in Genesis about

Eve, Hagar, and Rebecca. Furthermore, the narratives most sympathetic

to women in the Bible all derive from what scholars call the J source.

As best we can reconstruct, J wrote from the Judean court of King David.

It is possiblealthough not extremely likely-that in that courtly context,

women writers might have been able to author works beloved and authoritative

enough to later become part of the canon. Friedman's musings that J

might have been a woman in David's court formed the starting point [356] It is difficult

to argue that any part of the New Testament could have been written

by a woman. Nevertheless, various people have raised the question of

whether the gospel of John or the gospel of Luke might have had female

authors, although for different reasons. Some have speculated that the

mysterious "beloved disciple" on whose breast J esus reclines

his head at the Last Supper (13:23) might have been Mary Magdalene,

who later composed some of the earliest material in that gospel, but

there are too many reasons to discount this hypothesis. Even if we set

aside the issue of whether or not a woman would have been literate enough

to compose early gospel material, Mary Magdalene lived in the early

first century-rather earlier than even our earliest gospel. As for the

gospel of Luke, many have pointed out that Luke renders the character

of Jesus' mother, Mary, more fully than other gospel writers. In particular,

Luke's treatment of the conception and birth of Jesus-the so-called

infancy narrative that opens the gospel (Luke 1:52:52)-gives the character

of Mary both agency and dialogue. Indeed, it is worth comparing Matthew's

infancy narrative, in which the angel of the Lord appears to Joseph

and tells him that Mary is to conceive, with Luke's infancy narrative,

in which Gabriel appears to Mary (and never to Joseph, who plays only

a vestigial role here). We can read Mary's response to the angel's words

expressed both through a description of her emotional state ("She

was deeply disturbed by these words and asked herself what the greeting

could mean," Luke 1 :29) and in her dialogue ("Mary said to

the angel, 'But how can this come about, since I have no knowledge of

man?'" Luke 1 :34). Mary's hymn of praise known as the Magnificat

(Luke 1:46-79), finally, is unique in New Testament literature (although

it draws heavily on Old Testament archetypes, particularly Hannah's

Song of Praise on the birth of her son, Samuel) (1 Sam. 2:1-10); in

it, Mary sings not merely as a woman, but as a prophet and the bearer

of the Messiah. In the entire New Testament, Luke's infancy narrative

reveals at the very least an authorial sensitivity toward women, and

the desire to define a female character in terms at least as rich and

nuanced as male characters. But it is wise to be thoughtful about what we, as readers, are really doing and thinking when we suspect that just because a female charac- ________________________________

Patricia Demers,

Women as Interpreters of the Bible (New York: Paulist Press,

1992). Carol A. Newsom and Sharon H. Ringe, eds., Women's Bible Commentary.

Expanded, with Apocrypha (Louisville WestrninsterlJohn Knox Press,

1998). |

||

|

|