|

Reserve Text: Roger Brown and Albert Gilman, The Pronouns of Power and Solidarity THE PRONOUNS OF

POWER AND SOLIDARITY This paper is divided into five major sections.1 The first three of these are concerned with the semantics of the pronouns of address. ~y seman~ tics we mean covariation between the pronoun used and the objective relationship existing between speaker and addressee. The first section offers a general description of the_semant:!.c evolution of the pronouns of address in certain European languages. The second section describes I semantic differences existing today among the pronouns of French, German, and Italian. The third section proposes a connection between social structure, group ideology, and the semantics of the pronoun. !l!~_~final. two sections of the paper are concerned with expressive style by which we meaii-covariation between the "pronoun used and characteristics of _______________________________ |

|

|

[253]

In each section

the evidence most important to the thesis of that section is described

in detail. However, the various generalizations we shall offer have

developed as an interdependent set from continuing study of our whole

assemblage of facts, and so it may be well to indicate here the sort

of motley assemblage this is. Among secondary sources the general language

histories (16, 48, 90, 142, 213, 275) have been of little use because

their central concernjs always phonetic rather than semantic change.

However, there are a small number of monographs and doctoral dissertations

describing the detailed pronoun semantics for one or another language

-sometimes throughout its history (133, 139, 216, 353), sometimes for

only a century or so (229, 401), and sometimes for the, works of a particular

author (55,119). As primary evidence for the usage of the past we have

drawn on plays, on legal proceedings (208), and on letters (89, 151).

We have also learned about contemporary usage from literature but, more

importantly, from long conversations with native speakers of French,

Italian, German, and Spanish both here and in Europe. Our best information

about the pronouns of today comes from a questionnaire concerning usage

which is described in the second section of this paper. The questionnaire

has thus far been answered by the following numbers of students from

abroad who were visiting in Boston in 1957-1958: 50 Frenchmen, 20 Germans,

11 Italians, and two informants, each, from Spain, Argentina, Chile,

Denmark, Norway, Sweden, Israel, South Africa, India, Switzerland, Holland,

Austria, and Yugoslavia. We have far more

information concerning English, French, Italian, Spanish, and German

than for any other languages. Informants and documents concerning the

other Indo-European languages are not easily accessible to us. What

we have to say is then largely founded on information about these five

closely related languages. These first conclusions will eventually be

tested by us against other Indo-European languages and, in a more generalized

form, against unrelated languages. The European development

of two singular pronouns of address begins with the Latin tu and vos.

In Italian they became tu and voi (with Lei eventually largely displacing

VOL); in French tu and vous; in Spanish tu and vos (later usted). In

German the distinction began with du and Ihr but Ihr gave way to er

and later to Sie. English speakers first used "thou" and "ye"

and later replaced "ye" with "you". As a convenience we propose to use

the symbols T and V (from the Latin tu and vos) as generic designators

for a familiar and a polite pronoun in any language. THE GENERAL

SEMANTIC EVOLUTION OF T AND V The usage need

not have been mediated by a prosaic association with actual plurality,

for plurality is a very old and ubiquitous metaphor for power. Consider

only the several senses of such English words as "great" and

"grand". The reverential vos could have been directly inspired

by the power of an emperor. Eventually the

Latin plural was extended from the emperor to other power figures. However,

this semantic pattern was not unequivocally established for many centuries.

There was much inexplicable fluctuation between T and V in Old French,

Spanish, Italian, and Portuguese (353), and in Middle English (229,

401). In verse, at least, the choice seems often to have depended on

assonance, rhyme, or syllable count. However, some time between the

twelfth and fourteenth centuries (133, 139, 229, 353), varying with

the language, a set of norms crystallized which we call the nonreciprocal

power semantic. The Power Semantic There are many

bases of power -physical strength, wealth, age, sex, institutionalized

role in the church, the state, the army, or within the family. The character

of the power semantic can be made clear with a set of examples from

various languages. In his letters, Pope Gregory I (590604) used T to

his subordinates in the ecclesiastical hierarchy and they invariably

said V to him (291). In medieval Europe, generally, the nobility said

T to the common people and received V,' the master of a household said

T to his slave, his servant, his squire, and received V. Within the

family, of whatever social level, parents gave T to children and were

given V. In Italy in the fifteenth century penitents said V to the priest

and were told T (139). In Froissart (late fourteenth century) God says

T to His angels and they say V; all celestial beings say T to man and

receive V. In French of the twelfth and thirteenth centuries man says

T to the animals (353). In fifteenth-century Italian literature Christians

say T to Turks and Jews and receive V (139). In the plays of Corneille

and Racine (353) and Shakespeare (55), the noble principals say T to

their subordinates and are given V in return. The V of reverence

entered European speech as a form of address to the principal power

in the state and eventually generalized to the powers within that microcosm

of the state -the nuclear family. In the history of language, then,

parents are emperor figures. It is interesting to note in passing that

Freud reversed this terminology and spoke of kings, as well as generals,

employers, and priests, as father figures. The propriety of Freud's

designation for his psychological purposes derives from the fact that

an individual learning a European language reverses the historical order

of semantic generalization. The individual's first experience of subordination

to power and of the reverential V comes in his relation to his parents.

In later years similar asymmetrical power relations and similar norms

of address develop between employer and employee, soldier and officer,

subject and monarch. We can see how it might happen, as Freud believed,

that the later social relationships would remind the individual of the

familial prototype and would revive emotions and responses from childhood.

In a man's personal. history recipients of the nonreciprocal V are parent

figures. Since the nonreciprocal power semantic only prescribes usage between superior and inferior, it calls for a social structure in which there are unique power ranks for every individual. Medieval European societies were not so finely structured as that, and so the power semantic was never the only rule for the use of T and V. There were also norms of address for persons of roughly equivalent power, that is, for members of a common class. Between equals, pronominal address was reciprocal; an individual gave and received the same form. During the medieval period, and for varying times beyond, equals of the upper classes exchanged the mutual V and equals of the lower classes exchanged T.

|

|

|

[256] The difference

in class practice derives from the fact that the reverential V was always

introduced into a society at the top. In the Roman Empire only the highest

ranking persons had any occasion to address the emperor, and so at first

only they made use of V in the singular. In its later history in other

parts of Europe the reverential V was usually adopted by one court in

imitation of another. The practice slowly disseminated downward in a

society. In this way the use of V in the singular incidentally came

to connote a speaker of high status. In later centuries Europeans became

very conscious of the extensive use of V as a mark of elegance. In the

drama of seventeenth-century France the nobility and bourgeoisie almost

always address one another as V. This is true even of husband and wife,

of lovers, and of parent and child if the child is adult. Mme. de Sevigne

in her correspondence never uses T, not even to her daughter the Comtesse

de Grignan (353). Servants and peasantry, however, regularly used T

among themselves. For many centuries

French, English, Italian, Spanish, and German pronoun usage followed

the rule of nonreciprocal T -V between persons of unequal power and

the rule of mutual V or T (according to social class membership) between

persons of roughly equivalent power. There was at first no rule differentiating

address among equals but, very gradually, a distinction developed which

is sometinies called the T of intimacy and the V of formality. We name

this second dimension solidarity, and here is our guess as to how it

developed. The Solidarity

Semantic As two people move apart on these power-laden dimensions, one of them begins to say V. In general terms, the V form is linked with differences between persons. Not all differences between persons imply a difference of power. Men are born in different cities, belong to different families of the same status, may attend different but equally prominent schools, may practice different but equally respected professions. A rule for making distinctive use of T and V among equals can be formulated by generalizing the power semantic. Differences of power cause V to emerge both directions. The relations called

older than, parent of, employer of, richer than,

stronger than, and nobler than are all asymmetrical. If

A is older than B, B is not older

than A. The relation called "more powerful than", which is

abstracted from these more specific relations, is also conceived to

be asymmetrical. The pronoun usage expressing this power relation is

also asymmetrical or nonreciprocal, with the greater receiving V and

the lesser T. Now we are concerned with a new set of relations which

are symmetrical; for example, attended the same school or have the same

parents or practice the same profession. If A has the same parents as

B, B has the same parents as A. Solidarity is the name we give to the

general relationship and solidarity is symmetrical. The corresponding

norms of address are symmetrical or reciprocal with V becoming more

probable as solidarity declines. The solidary T reaches a peak of probability

in address between twin brothers or in a man's soliloquizing address

to himself. Not every personal attribute counts in determining whether two people are solidary enough to use the mutual T. Eye color does not ordinarily matter nor does shoe size. The similarities that matter seem to be those that make for like-mindedness or similar behavior dispositions. .These will ordinarily be such things as political membership, family, religion, profession, sex, and birthplace. However, extreme

distinctive values on almost any dimension may become significant. Height

ought to make for solidarity among giants and midgets. The T of solidarity

can be produced by frequency of contact as well as by objective similarities.

However, frequent contact does not necessarily lead to the mutual T.

It depends on whether contact results in the discovery or creation of

the like-mindedness that seems to be the core of the solidarity semantic.

The dimension of

solidarity is potentially applicable to all persons addressed. Power

superiors may be solidary (parents, elder siblings) or not solidary

(officials whom one seldom sees). Power inferiors, similarly, may be

as solidary as the old family retainer and as remote as the waiter in

a strange restaurant. Extension of the solidarity dimension along the

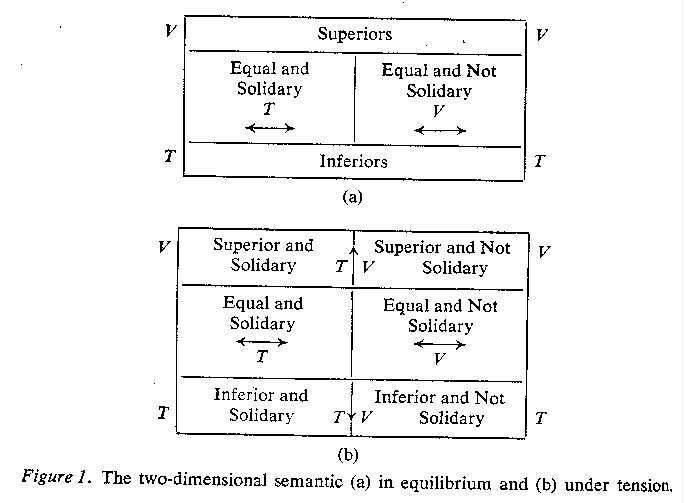

dotted lines of Figure 1 b creates six categories of persons defined

by their relations to a speaker. Rules of address are in conflict for

persons in the upper left and lower right categories. For the upper

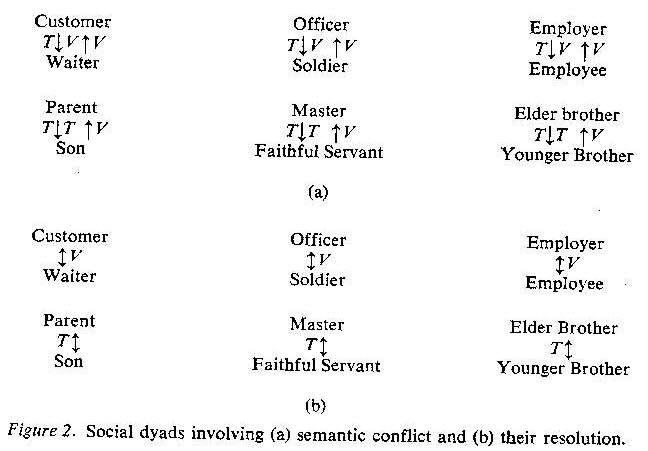

left, power in The asbtract conflict described in Figure 1 b is particularized in Figure 2a with a sample of the social dyads in which the conflict would be felt. In each case usage in one direction is unequivocal but, in the other direction, the two semantic forces are opposed. The first three dyads in Figure 2a involve conflict in address to inferiors who are not solidary (the lower right category of Figure 1 b), and the second three dyads involve conflict in address to superiors who are solidary (the upper left category in Figure Ib).

It is the present

practice to reinterpret power-laden attributes so as to turn to them

into symmetrical solidarity attributes. Relationships like older than,

father of, nobler than, and richer than are now reinterpreted for purposes of

T and Vas relations of the same age as, the same family as, the same

kind of ancestry as, and the same income as. In the degree that these

relationships hold, the probability of a mutual T increases and, There is an interesting

residual of the power relation in the contemporary notion that the right

to initiate the reciprocal T belongs to the member of the dyad having

the better power-based claim to say T without reciprocation. The suggestion

that solidarity be recognized comes more grace fully from the elder

than from the younger, from the richer than from the poorer, from the

employer than from the employee, from the noble In support of our

claim that solidarity has largely won out over power we can offer a

few quotations from language scholars. Littre, writing of French usage,

says (251): "Notre courtoisie est meme si grande, que The best evidence that the change has occurred is in our interviews and notes on contemporary literature and films and, most importantly, the questionnaire results. The six social dyads of Figure 2 were all repre- [260] Finally, it is

our opinion that a still newer direction of semantic shift can be discerned

in the whole collection of languages studied. Once solidarity has been

established as the single dimension distinguishing T from V the province

of T proceeds to expand. The direction of change is increase in the

number of relations defined as solidary enough to merit a mutual T and,

in particular, to regard any sort of camaraderie resulting from a common

task or a common fate as grounds for T. We have a favorite example of

this new trend given us independently by several French informants.

It seems that mountaineers above a certain critical altitude shift to

the mutual T. We like to think that this is the point where their lives

hang by a single thread. In general, the mutual T is advancing among

fellow students, fellow workers, members of the same political group,

persons who share a hobby or take a trip together. We believe this is

the direction of current change because it summarizes what our, informants

tell us about the pronoun usage of the "young people" as opposed

to that of older people. CONTEMPORARY

DIFFERENCES AMONG FRENCH, ITALIAN, AND GERMAN The questionnaire

is in English. It opens with a paragraph informing the subject that

the items below all have reference to the use of the singular pronouns

of address in his native language. There are 28 items in the full questionnaire,

and they all have the form of the following example from the questionnaire

for French students: [261]

The questionnaire

asks about usage between the subject and his mother, his father, his

grandfather, his wife, a younger brother who is a child, a married elder

brother, that brother's wife, a remote male cousin, and an elderly female

servant whom he has known from childhood. It asks about usage between

the subject and fellow students at the university at home, usage to

a student from home visiting in America, and usage to someone with whom

the subject had been at school some years previously. It asks about

usage to a waiter in a restaurant, between clerks in an office, fellow

soldiers in the army, between boss and employee, army private and general.

In addition, there are some rather elaborate items' which ask the subject

to imagine himself in some carefully detailed social situation and then

to say what pronoun he would use. A copy of the full questionnaire may

be had on application to the authors. The most accessible informants were students from abroad resident in Boston in the fall of 1957. Listings of such students were obtained from Harvard, Boston University, M.I.T., and the Office of the French Consul in New England. Although we have data from a small sample of female respondents, the present analysis is limited to the males. All the men in the sample have been in the United States for one year or less; they come from cities of over 300,000 inhabitants, and these cities are well scattered across the country in qucstion. In addition, all members of the sample are from upper-middle-class, professional families. This homogeneity of class membership was enforced by the factors determining selection of students who go abroad. The occasional informant from a working-class family is deliberately excluded from these comparisons. The class from which we draw shows less regional variation in speech than does the working class and, especially, farmers. At the present time we have complete responses from 50 Frenchmen, 20 Germans, and 11 Italians; many of these men also sent us letters describing their understanding of the pronouns and offering numerous valuable anecdotes of usage. The varying numbers of subjects belonging to the three nationalities result from the unequal representation of these nationalities among Boston students rather than from national characterological differences in willingness to answer a questionnaire. Almost every person 'on our lists agreed to serve as an informant.. In analyzing the

results we assigned the numbers 0-4 to the five response alternatives

to each question, beginning with "Definitely V" as O. A rough

test was made of the significance of the differences among the three

languages on each question. We dichotomized the replies to each question

into: (a) all replies of either "Definitely T' or "Probably

T'; (b) all replies of "Definitely V" or "Probably V"

or "Possibly V, possibly T". Using the chi-squared test with

Yates's correction for small frequencies we determined, for each comparison,

the probability of obtaining by chance a difference as large or larger

than that actually obtained. Even with such small samples, there were

quite a few differences significantly unlikely to occur by chance (P

= .05 or less). Germans were more prone than the French to say T to

their grandfathers, to an elder brother's wife, and to an old family

servant. The French were more prone than the Germans to say T to a male

fellow student, to a student from home visiting in America, to a fellow

clerk in an office, and to someone known previously as a fellow student.

Italians were more prone than the French to say T to a female fellow

student and also to an attractive girl to whom they had recently been

introduced. Italians were more prone than the Germans to say T to the

persons just described and, in addition, to a male fellow student and

to a student from home visiting in America. On no question did either

the French or the Germans show a significantly greater tendency to say

T than did the Italians. The many particular

differences among the three languages are susceptible of a general characterization.

Let us first contrast German and French. The German T is more reliably

applied within the family than is the French T; in addition to the significantly

higher T scores for grandfather and elder brother's wife there are smaller

differences showing a higher score for the German T on father, mother,

wife, married elder bother, and remote male cousin. The French T is

not automatically applied to remote relatives, but it is more likely

than the German pronoun to be used to express the camaraderie of fellow

students, fellow clerks, fellow countrymen abroad, and fellow soldiers.

In general it may be said that the solidarity coded by the German T

is an ascribed solidarity of family relationships. The French T, in

greater degree, codes an acquired solidarity not founded on family relationship

but developing out of some sort of shared fate. As for the Italian T,

it very nearly equals the German in family solidarity and it surpasses

the French in camaraderie. The camaraderie of the Italian male, incidentally,

is extended to the Italian female; unlike the French or German student

the Italian says T to the co-ed almost as readily as to the male fellow

student. There is a very

abstract semantic rule governing T and V which is the same for French,

German, and Italian and for many other languages we have studied: The

rule is that usage is reciprocal, T becoming increasing- Iy probable and

V less probable as the number of solidarity-producing attributes shared

by two people increases. The respect in which French, German, and Italian

differ from one another is in the relative weight given to various attributes

of persons which can serve to generate solidarity. For German, ascribed

family membership is the important attribute; French and Italian give

more weight to acquired characteristics. SEMANTICS, SOCIAL

STRUCTURE AND IDEOLOGY In France the nonreciprocal

power semantic was dominant until the Revolution when the Committee

for the Public Safety condemned the use of V as a feudal remnant and

ordered a universal reciprocal T. On October 31, 1793, Malbec made a

Parliamentary speech against V: "Nous distinguons trois personnes

pour Ie singulier et trois pour Ie pluriel, et, au mepris de cette regIe,

l'esprit de fa1:Iatisme, d'orgueil et de feodalite, nous a fait contracter

l'habitude de nous servir de la seconde personne du pluriellorsque nous

parlons a un seul" (quoted in 49). For a time revolutionary "fraternite"

transformed all address into the mutual Citoyen and the mutual tu. Robespierre

even addressed the president of the Assembly as tu. In later years solidarity

declined and the differences of power which always exist everywhere

were expressed once more. It must be asked

why the equalitarian ideal was expressed in a universal T rather than

a universal V or, as a third alternative, why there was not a shift

of semantic from power to solidarity with both pronouns being retained.

The answer lies with the ancient upper-class preference for the use

of V. There was animus against the pronoun itself. The pro- Although the power

semantic has largely gone out of pronoun use in France today native

speakers are nevertheless aware of it. In part they are aware of it

because it prevails in so much of the greatest French literature. Awareness

of power as a potential factor in pronoun usage was revealed by our

respondents' special attitude toward the saying of T to a waiter. Most

of them felt that this would be shockingly bad taste in a way that other

norm violations would not be, apparently because there is a kind of

seignorial right to say T to a waiter, an actual power assymmetry, which

the modern man's ideology requires him to deny. In French Africa, on

the other hand, it is considered proper to recognize a caste difference

between the Mrican and the European, and the nonreciprocal address is

used to express it. The European says T and requires V from the African.

This is a galling custom to the African, and in 1957 Robert Lacoste,

the French Minister residing in Algeria, urged his countrymen to eschew

the practice. In England, before

the Norman Conquest, "ye" was the second person plural and

"thou" the singular. "You" was originally the accusative

of "ye", but in time it also became the nominative plural

and ultimately ousted "thou" as the usual singular. The first

uses of "ye" as a reverential singular occur in the thirteenth

century (229), and seem to have been copied from the French nobility.

The semantic progression corresponds roughly to the general stages described

in the first section of this paper, except that the English seem always

to have moved more freely from one form to another than did the continental

Europeans (213). In the seventeenth century "thou" and "you" became explicitly involved in social controversy. The Religious Society of Friends (or Quakers) was founded in the middle of this century by George Fox. One of the practices setting off this rebellious group from the larger society was the use of Plain Speech, and this entailed saying "thou" to everyone. , George Fox explained the practice in these words:

[265] (118), in which

he argued that the Scriptures show that God and Adam and God and Moses

were not too proud to say and receive the singular T. For the new convert

to the Society of Friends the universal T was an especially difficult

commandment. Thomas Ellwood has described (112) the trouble that developed

between himself and his father: But whenever I

had occasion to speak to my Father, though I had no Hat now to offend

him; yet my language did as much: for I durst not say YOU to him, but

THOU or THEE, as the Occasion required, and then would he be sure to

fall on me with his Fists. The Friends' reasons

for using the mutual T were much the same as those of the French revolutionaries,

but the Friends were always a minority and the larger society was antagonized

by their violations of decorum. Some Friends use

"thee" today; the nominative "thou" has been dropped

and "thee" is used as both the nominative and (as formerly)

the accusative. Interestingly, many Friends also use "you".

"Thee" is likely to be reserved for Friends among themselves

and "you" said to outsiders. This seems to be a survival of

the solidarity semantic. In English at large, of course, "thou"

is no longer used. The explanation of its disappearance is by no means

certain; however, the forces at work seem to have included a popular

reaction against the radicalism of Quakers and Levelers and also a general

trend in English toward simplified verbal inflection. In the world today

there are numerous examples of the association proposed between ideology

and pronoun semantics. In Yugoslavia, our informants tell us, there

was, for a short time following the establishment of Communism, a universal

mutual T of solidarity. Today revolutionary esprit has declined and

V has returned for much the same set of circumstances as in Italy, France,

or Spain. There is also some power asymmetry in Yugoslavia's "Socialist

manners". A soldier says V and Comrade General, but the general

addresses the soldier with T and surname. It is interesting in our materials to contrast usage in the Afrikaans language of South Africa and in the Gujerati and Hindi languages of India \lith the rest of the collection. On the questionnaire, Afrikaans speakers made eight nonreciprocal power distinctions; especially notable are distinctions within the family and the distinctions between customer and waiter and between boss and clerk, since these are almost never powercoded in French, Italian, German, etc., although they once were. The Afrikaans pattern generally preserves the asymmetry of the dyads described in Figure 2, and that suggests a more static society and a less developed equalitarian ethic. The forms of address used between [266] Afrikaans-speaking

whites and the groups of "coloreds" and "blacks"

are especially interesting. The Afrikaaner uses T, but the two lower

castes use neither T nor V. The intermediate caste of "coloreds"

says Meneer to the white and the "blacks" say Baas. It is

as if these social distances transcend anything that can be found within

the white group and so require their peculiar linguistic expressions. The Gujerati and

Hindi languages of India have about the same pronoun semantic, and it

is heavily loaded with power. These languages have all the asymmetrical

usage of Afrikaans and, in addition, use the nonreciprocal T and V between

elder brother and younger brother and between husband and wife. This

truly feudal pronominal pattern is consistent with the static Indian

society. However, that society is now changing rapidly and, consistent

with that change, the norms of pronoun usage are also changing. The

progressive young Indian exchanges the mutual T with his wife. In our account

of the general semantic evolution of the pronouns, we have identified

a stage in which the solidarity rule was limited to address between

persons of equal power. This seemed to yield a two-dimensional system

in equilibrium (see Figure la), and we have wondered why address did

not permanently stabilize there. It is possible, of course, that human

cognition favors the binary choice without contingencies and so found

its way to the suppression of one dimension. However, this theory does

not account for the fact that it was the rule of solidarity that triumphed.

We believe, therefore, that the development of open societies with an

equalitarian ideology acted against the nonreciprocal power semantic

and in favor of solidarity. It is our suggestion that the larger social

changes created a distaste for the face-to-face expression of differential

power. What of the many

actions other than nonreciprocal T and V which express power asymmetry?

A vassal not only says V but also bows, lifts his cap, touches his forelock,

keeps silent, leaps to obey. There are a large number of expressions

of subordination which are patterned isomorphically with T and V. Nor

are the pronouns the only forms of nonreciprocal address. There are,

in addition, proper names and titles, and many of these operate today

on a nonreciprocal power pattern in America and in Europe, in open and

equalitarian societies. In the American family there are no discriminating pronouns, but there are nonreciprocal norms of address. A father says "Jim" to his son but, unless he is extraordinarily "advanced", he does not anticipate being called "Jack" in reply. In the American South there are no pronouns to mark the caste separation of Negro and white, but there are nonreciprocal norms of address. The white man is accustomed to call the Negro by his first name, but he expects to be called "Mr. Legree". In America and Differences of

power exist in a democracy as in all societies. What is the difference

between expressing power asymmetry in pronouns and expressing it by

choice of title and proper name? It seems to be primarily a question

of the degree of linguistic compulsion. In face-to-face address we can

usually avoid the use of any name or title but not so easily the use

of a pronoun. Even if the pronoun can be avoided, it will be implicit

in the inflection of the verb. "Dites quelque chose" clearly

says vous to the Frenchman. A norm for the pronominal and verbal expression

of power compels a continuing coding of power, whereas a norm for titles

and names permits power to go uncoded in most discourse. Is there any

reason why the pronominal coding should be more congenial to a static

society than to an open society? We have noticed

that mode of address intrudes into consciousness as a problem at times

of status change. Award of the doctoral degree, for instance, transforms

a student into a colleague and, among American academics, the familiar

first name is normal. The fledgling academic may find it difficult to

call his former teachers by their first names. Although these teachers

may be young and affable, they have had a very real power over him for

several years and it will feel presumptuous to deny this all at once

with a new mode of addres£. However, the "tyranny of democratic

manners" (77) does not allow him to continue comfortable with the

polite "Professor X". He would not like to be thought unduly

conscious of status, unprepared for faculty rank, a born lickspittle.

Happily, English allows him a respite. He can avoid any term of address,

staying with the uncommitted "you", until he and his addressees

have got used to the new state of things. This linguistic rite de paS'sage

has, for English speakers, a waiting room in which to screw up courage. In a fluid society

crises of address will occur more frequently than in a static society,

and so the pronominal coding of power differences is more likely to

be felt as onerous. Coding by title and name would be more tolerable

because less compulsory. Where status is fixed by birth and does not

change each man has enduring rights and obligations of address. A strong equalitarian

ideology of the sort dominant in America works to suppress every conventional

expression of power asymmetry. If the worker becomes conscious of his

unreciprocated polite address to the boss, he may feel that his human

dignity requires him to change. However, we do not feel the full power

of the ideology until we are in a situation that gives us some claim

to receive deferential address. The American professor often feels foolish

being given his title, he almost certainly [268] GROUP STYLE

WITH THE PRONOUNS OF ADDRESS Linguistic science

finds enough that is constant in English and French ,and Latin to put

all these and many more into one family -the IndoEuropean. It is possible

with reference to this constancy to think of Italian and Spanish and

English and the others as so many styles of .Indo-European. They all

have, for instance, two singular pronouns of :address, but each language

has an individual phonetic and semantic style in pronoun usage. We are

ignoring phonetic style (through the use of the generic T and V), but

in the second section of the paper we have described differences in

the semantic styles of French, German, and Italian. Linguistic styles

are potentially expressive when there is covariation between characteristics

of language performance and characteristics of the performers. When

styles are "interpreted", language behavior is functionally

expressive. On that abstract level where the constancy is Indo-European

and the styles are French, German, English, and Italian, interpretations

of style must be statements about communities of speakers, statements

of national character, social structure, or group ideology. .In the

last section we have hazarded a few propositions on this level. It is usual, in

discussion of linguistic style, to set constancy at the level of a language

like French or English rather than at the level of a language family.

In the languages we have studied there are variations in pronoun style

that are associated with the social status of the speaker. We have seen

that the use of V because of its entry at the top of a society and its

diffusion downward was always interpreted as a mark of good [269] In literature,

pronoun style has often been used to expose the pretensions of social

climbers and the would-be elegant. Persons aping the manners of the

class above them usually do not get the imitation exactly right. They

are likely to notice some point of difference between their own class

and the next higher and then extend the difference too widely, as in

the use of the "elegant" broad [a] in "can" and

"bad". Moliere gives us his "precieuses ridicules"

saying V to servants whom a refined person would call T. In Ben Jonson's

Everyman in his Humour and Epicoene such true gallants as Wellbred and

Knowell usually say "you" to one another but they make frequent

expressive shifts between this form and "thou", whereas such

fops as John Daw and Amorous-La-Foole make unvarying use of "you". Our sample of visiting

French students was roughly homogeneous in social status as judged by

the single criterion of paternal occupation. Therefore, we could not

make any systematic study of differences in class style, but we thought

it possible that, even within this select group, there might be interpretable

differences of style. It was our guess that the tendency to make wide

or narrow use of the solidary T would be related to general radicalism

or conservatism of ideology. As a measure of this latter dimension we

used Eysenck's Social Attitude Inventory (117). This is a collection

of statements to be accepted or rejected concerning a variety of matters

-religion, economics, racial relations, sexual behavior, etc. Eysenck

has validated the scale in England and in France on members of Socialist,

Communist, Fascist, Conservative, and Liberal party members. In general,

to be radical on this scale is to favor change and to be conservative

is to wish to maintain the status quo or turn back to some earlier condition.

We undertook to relate scores on this inventory to an index of pronoun

style. As yet we have

reported no evidence demonstrating that there exists such a thing as

a personal style in pronoun usage in the sense of a tendency to make

wide or narrow use of T. It may be that each item in the ques- . tionnaire,

each sort of person addressed, is an independent personal

|

|

|

norm not predicatble

from any other. A child learns what to say to each kind of person. What

he learns in each case depends on the groups in which he has membership.

Perhaps his usage is a bundle of unrelated habits. Guttman (402) has

developed the technique of Scalogram Analysis for determining whether

or not a collection of statements taps a common dimension. A perfect

Guttman scale can be made of the statements: (a) I am at least 5' tall;

(b) I am at least 5' 4" tall; (c) I am at least 5' 7" tall;

(d) I am at least 6' 1" tall; (e) I am at least 6' 2" tall.

Endorsement of a more extreme statement will always be associated with

endorsement of all less extreme statements. A person can be assigned

a single score -a, b, c, d, or e -which represents the most extreme

statement he has endorsed and, from this single score, all his individual

answers can be reproduced. If he scores c he has also endorsed a and

b but not d or e. The general criterion for scalability is the reproducibility

of individual responses from a single score, and this depends on the

items being interrelated so that endorsement of one is reliably associated

with endorsement or rejection of the others. The Guttman method

was developed during World War II for the measurement of social attitudes,

and it has been widely used. Perfect reproducibility is not likely to

be found for all the statements which an investigator guesses to be

concerned with some single attitude. The usual thing is to accept a

set of statements as scalable when they are 90 per The responses to

the pronoun questionnaire are not varying degrees of agreement (as in

an attitude questionnaire) but are rather varying probabilities of saying

T or V. There seems to be no reason why these bipolar responses cannot

be treated like yes or no responses on an attitude scale. The difference

is that the scale, if there is one, will be the semantic dimension governing

the pronouns, and the scale score of each respondent will represent

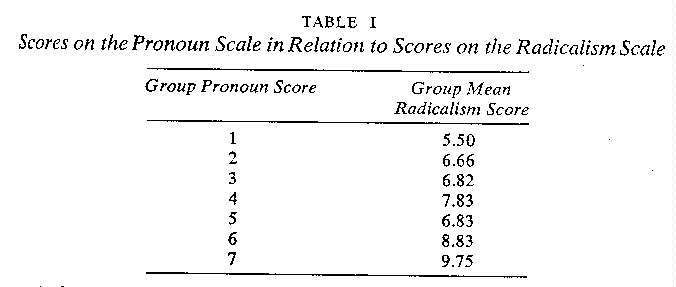

his personal semantic style. It is customary to have 100 subjects for a Scalogram Analysis, but we could find only 50 French students. We tested all 28 items for scalability and found that a subset of them made a fairly good scale. It was necessary to combine response categories so as to dichotomize them in order to obtain an average reproducibility of 85 per cent. This coefficient was computed for the five intermediate items having the more-balanced marginal frequencies. A large number of items fell at or very near the two extremes. The solidarity or T -most end of the scale could be defined by father, mother, elder brother, young boys, wife, or lover quite as well as by younger brother. The remote or V-most end could be defined by [271] For each item on

the scale a T answer scores one point and a V answer no points. The

individual total scores range from 1 to 7, which means the scale can

differentiate only seven semantic styles. We divided the subjects into

the resultant seven stylistically homogeneous groups and, for each group,

determined the average scores on radicalism-conservatism. There was

a set of almost perfectly consistent differences.

There is enough

consistency of address to justify speaking of a personal-pronoun style

which involves a more or less Wide use of the solidary T. Even among

students of the same, socio-economic level there are differences of

style, and these are potentially expressive of radicalism and conservatism

in ideology. A Frenchman could, with some confidence, infer that a male

university student who regularly said T to female fellow students would

favor the nationalization of industry, free love, trial marriage, the

abolition of capital punishment, and the weakening of nationalistic

and religious loyalties. What shall we make of the association between a wide use of T and a cluster of radical sentiments? There may be no "sense" to it at all, that is, no logical connection between the linguistic practice and the attitudes, but simply a general tendency to go along with the newest thing. We know that left-wing attitudes are more likely to be found in the On the other hand perhaps there is something appropriate in the association. The ideology is consistent in its disapproval of barriers between people: race, religion, nationality, property, marriage, even criminality. All these barriers have the effect of separating the solidary, the "ingroup", from the nonsolidary, the "out-group". The radical says the criminal is not far enough "out" to be killed; he should be re-educated. He says that a nationality ought not to be so solidary that it prevents world organization from succeeding. Private property ought to be abolished, industry should be nationalized. There are to be no more outgroups and in-groups but rather one group, undifferentiated by nationality, religion, or pronoun of address. The fact that the pronoun which is being extended to all men alike is T, the mark of solidarity, the pronoun of the nuclear family, expresses the radical's intention to extend his sense of brotherhood. But we notice that the universal application of the pronoun eliminates the discrimination that gave it a meaning and that gives particular point to an old problem. Can the solidarity of the family be extended so widely? Is there enough libido to stretch so far? Will there perhaps be a thin solidarity the same everywhere but nowhere so strong as in the past? ..

Sometimes the choice of a pronoun clearly violates a group norm and perhaps also the customary practice of the speaker. Then the meaning of the act will be sought in some attitude or emotion of the speaker. It is as if the interpreter reasoned that variations of address between the same two persons must be caused by variations in their attitudes toward one another. If two men of seventeenth-century France properly exchange As there have been

two great semantic dimensions governing T and V, so there have also

been two principal kinds of expressive meaning. Breaking the norms of

power generally has the meaning that a speaker regards an addressee

as his inferior, superior, or equal, although by usual criteria, and

according to the speaker's own customary usage, the addressee is not

what the pronoun implies. Breaking the norms of solidarity generally

means that the speaker temporarily thinks of the other as an outsider

or as an intimate; it means that sympathy is extended or withdrawn. Racine, in his

dramas, used the pronouns with perfect semantic consistency. His major

figures exchange the V of upper-class equals. Lovers, brother and sister,

husband and wife -none of them says T if he is of high rank, but each

person of high rank has a subordinate confidante to whom he says T and

from whom he receives V. It is a perfect nonreciprocal power semantic.

This courtly pattern is broken only for the greatest scenes in each

play. Racine reserved the expressive pronoun as some composers save

the cymbals. In both Andromaque and Phedre there are only two expressive

departures from the norm, and they mark climaxes of feeling. Jespersen (213)

believed that English "thou" and "ye" (or "you")

were more often shifted to express mood and tone than were the pronouns

of the continental languages, and our comparisons strongly support this

opinion. The "thou" of contempt was so very familiar that

a verbal form was created to name this expressive use. Shakespeare gives The T of contempt

and anger is usually introduced between persons who normally exchange

V but it can, of course, also be used by a subordinate to a superior.

As the social distance is greater, the overthrow of the norm is more

shocking and generally represents a greater extremity of passion. Sejanus,

in Ben Jonson's play of that name, feels extreme contempt for the emperor

Tiberius but wisely gives him the reverential V to his face. However,

soliloquizing after the emperor has exited. Sejanus begins: "Dull,

heavy Caesar! Wouldst thou tell me. .." In Jonson's Volpone

Mosca invariably says "you" to his master until the final

scene when, as the two villains are about to be carted away, Mosca turns

on Volpone with "Bane to thy wolfish nature." Expressive effects

of much greater subtlety than those we have described are common in

Elizabethan and Jacobean drama. The exact interpretation of the speaker's

attitude depends not only on the pronoun norm he upsets but also on

his attendant words and actions and the total setting. Still simple

enough to be unequivocal is the ironic or mocking "you" said

by Tamburlaine to the captive Turkish emperor Bajazeth. This exchange

occurs in Act IV of Marlowe's play:

The momentary shift

of pronoun directly expresses a momentary shift of mood, but that interpretation

does not exhaust its meaning. The fact that a man has a particular momentary

attitude or emotion may imply a great deal about his characteristic

disposition, his readiness for one kjDd of feeling rather than another.

Not every attorney general, for instance, would have used the abusive

"thou" to Raleigh. The fact that Edward Coke did so suggests

an arrogant and choleric temperament and, in fact, many made this assessment

of him (208). When Volpone spoke to Celia a lady of Venice, he ought

to have said "you" but he began at once witb [275]

With the establishment

of the solidarity semantic a new set of expressive meanings became possible-

feelings of sympathy and estrangement. In Shakespeare's plays there

are expressive meanings that derive from the solidarity semantic as

well as many dependent on power usage and many that rely on both connotations.

The play Two Gentlemen of Verona is concerned with the Renaissance

ideal of friendship and provides especially clear expressions of solidarity.

Proteus and Valentine, the two Gentlemen, initially exchange "thou",

but when they touch on the sub

We have suggested

that the modern direction of change in pronoun i ~5age expresses a will

to extend the solidary ethic to everyone. The apparent decline of expressive

shifts between T and V is more difficult to interpret. Perhaps it is

because Europeans have seen that excluded persons or races or groups

can become the target of extreme aggression _____________________________________ |